Pathway Specific Targeting in Anticancer Therapies

Writer and Curator: Larry H. Bernstein, MD, FCAP

7.7 Pathway specific targeting in anticancer therapies

7.7.1 Structural basis for the allosteric inhibitory mechanism of human kidney-type glutaminase (KGA) and its regulation by Raf-Mek-Erk signaling in cancer cell metabolism

7.7.2 Sonic hedgehog (Shh) signaling promotes tumorigenicity and stemness via activation of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in bladder cancer.

7.7.3 Differential activation of NF-κB signaling is associated with platinum and taxane resistance in MyD88 deficient epithelial ovarian cancer cells

7.7.4 Activation of apoptosis by caspase-3-dependent specific RelB cleavage in anticancer agent-treated cancer cells

7.7.5 Identification of Liver Cancer Progenitors Whose Malignant Progression Depends on Autocrine IL-6 Signaling

7.7.6 Acetylation Stabilizes ATP-Citrate Lyase to Promote Lipid Biosynthesis and Tumor Growth

7.7.7 Monoacylglycerol Lipase Regulates a Fatty Acid Network that Promotes Cancer Pathogenesis

7.7.8 Pirin regulates epithelial to mesenchymal transition and down-regulates EAF/U19 signaling in prostate cancer cells

7.7.9 O-GlcNAcylation at promoters, nutrient sensors, and transcriptional regulation

7.7.1 Structural basis for the allosteric inhibitory mechanism of human kidney-type glutaminase (KGA) and its regulation by Raf-Mek-Erk signaling in cancer cell metabolism

Thangavelua, CQ Pana, …, BC Lowa, and J. Sivaramana

Proc Nat Acad Sci 2012; 109(20):7705–7710

http://dx.doi.org:/10.1073/pnas.1116573109

Besides thriving on altered glucose metabolism, cancer cells undergo glutaminolysis to meet their energy demands. As the first enzyme in catalyzing glutaminolysis, human kidney-type glutaminase isoform (KGA) is becoming an attractive target for small molecules such as BPTES [bis-2-(5 phenylacetamido-1, 2, 4-thiadiazol-2-yl) ethyl sulfide], although the regulatory mechanism of KGA remains unknown. On the basis of crystal structures, we reveal that BPTES binds to an allosteric pocket at the dimer interface of KGA, triggering a dramatic conformational change of the key loop (Glu312-Pro329) near the catalytic site and rendering it inactive. The binding mode of BPTES on the hydrophobic pocket explains its specificity to KGA. Interestingly, KGA activity in cells is stimulated by EGF, and KGA associates with all three kinase components of the Raf-1/Mek2/Erk signaling module. However, the enhanced activity is abrogated by kinase-dead, dominant negative mutants of Raf-1 (Raf-1-K375M) and Mek2 (Mek2-K101A), protein phosphatase PP2A, and Mek-inhibitor U0126, indicative of phosphorylation-dependent regulation. Furthermore, treating cells that coexpressed Mek2-K101A and KGA with suboptimal level of BPTES leads to synergistic inhibition on cell proliferation. Consequently, mutating the crucial hydrophobic residues at this key loop abrogates KGA activity and cell proliferation, despite the binding of constitutive active Mek2-S222/226D. These studies therefore offer insights into (i) allosteric inhibition of KGA by BPTES, revealing the dynamic nature of KGA’s active and inhibitory sites, and (ii) cross-talk and regulation of KGA activities by EGF-mediated Raf-Mek-Erk signaling. These findings will help in the design of better inhibitors and strategies for the treatment of cancers addicted with glutamine metabolism.

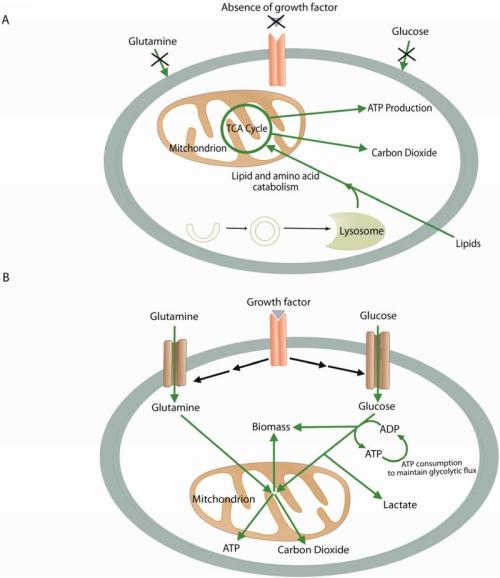

The Warburg effect in cancer biology describes the tendency of cancer cells to take up more glucose than most normal cells, despite the availability of oxygen (1, 2). In addition to altered glucose metabolism, glutaminolysis (catabolism of glutamine to ATP and lactate) is another hallmark of cancer cells (2, 3). In glutaminolysis, mitochondrial glutaminase catalyzes the conversion of glutamine to glutamate (4), which is further catabolized in the Krebs cycle for the production of ATP, nucleotides, certain amino acids, lipids, and glutathione (2, 5).

Humans express two glutaminase isoforms: KGA (kidney-type) and LGA (liver-type) from two closely related genes (6). Although KGA is important for promoting growth, nothing is known about the precise mechanism of its activation or inhibition and how its functions are regulated under physiological or pathophysiological conditions. Inhibition of rat KGA activity by antisense mRNA results in decreased growth and tumorigenicity of Ehrlich ascites tumor cells (7), reduced level of glutathione, and induced apoptosis (8), whereas Myc, an oncogenic transcription factor, stimulates KGA expression and glutamine metabolism (5). Interestingly, direct suppression of miR23a and miR23b (9) or activation of TGF-β (10) enhances KGA expression. Similarly, Rho GTPase that controls cytoskeleton and cell division also up-regulates KGA expression in an NF-κB–dependent manner (11). In addition, KGA is a substrate for the ubiquitin ligase anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C)-Cdh1, linking glutaminolysis to cell cycle progression (12). In comparison, function and regulation of LGA is not well studied, although it was recently shown to be linked to p53 pathway (13, 14). Although intense efforts are being made to develop a specific KGA inhibitor such as BPTES [bis-2-(5-phenylacetamido-1, 2, 4-thiadiazol-2-yl) ethyl sulfide] (15), its mechanism of inhibition and selectivity is not yet understood. Equally important is to understand how KGA function is regulated in normal and cancer cells so that a better treatment strategy can be considered.

The previous crystal structures of microbial (Mglu) and Escherichia coli glutaminases show a conserved catalytic domain of KGA (16, 17). However, detailed structural information and regulation are not available for human glutaminases especially the KGA, and this has hindered our strategies to develop inhibitors. Here we report the crystal structure of the catalytic domain of human apo KGA and its complexes with substrate (L-glutamine), product (L-glutamate), BPTES, and its derived inhibitors. Further, Raf-Mek-Erk module is identified as the regulator of KGA activity. Although BPTES is not recognized in the active site, its binding confers a drastic conformational change of a key loop (Glu312-Pro329), which is essential in stabilizing the catalytic pocket. Significantly, EGF activates KGA activity, which can be abolished by the kinase-dead, dominant negative mutants of Mek2 (Mek2-K101A) or its upstream activator Raf-1 (Raf-1-K375M), which are the kinase components of the growth-promoting Raf-Mek2-Erk signaling node. Furthermore, coexpression of phosphatase PP2A and treatment with Mek-specific inhibitor or alkaline phosphatase all abolished enhanced KGA activity inside the cells and in vitro, indicating that stimulation of KGA is phosphorylation dependent. Our results therefore provide mechanistic insights into KGA inhibition by BPTES and its regulation by EGF-mediated Raf-Mek-Erk module in cell growth and possibly cancer manifestation.

Structures of cKGA and Its Complexes with L-Glutamine and L-Glutamate.

The human KGA consists of 669 amino acids. We refer to Ile221-Leu533 as the catalytic domain of KGA (cKGA) (Fig. 1A). The crystal structures of the apo cKGA and in complex with L-glutamine or L-glutamate were determined (Table S1). The structure of cKGA has two domains with the active site located at the interface. Domain I comprises (Ile221-Pro281 and Cys424 -Leu533) of a five-stranded anti-parallel β-sheet (β2↓β1↑β5↓β4↑β3↓) surrounded by six α-helices and several loops. The domain II (Phe282-Thr423) mainly consists of seven α-helices. L-Glutamine/L-glutamate is bound in the active site cleft (Fig. 1B and Fig. S1B). Overall the active site is highly basic, and the bound ligand makes several hydrogen-bonding contacts to Gln285, Ser286, Asn335, Glu381, Asn388, Tyr414, Tyr466, and Val484 (Fig. 1C and Fig. S1C), and these residues are highly conserved among KGA homologs (Fig. S1D). Notably, the putative serine-lysine catalytic dyad (286-SCVK-289), corresponding to the SXXK motif of class D β-lactamase (17), is located in close proximity to the bound ligand. In the apo structure, two water molecules were located in the active site, one of them being displaced by glutamine in the substrate complex. The substrate side chain is within hydrogen-bonding distance (2.9 Å) to the active site Ser286. Other key residues involved in catalysis, such as Lys289, Tyr414, and Tyr466, are in the vicinity of the active site. Lys289 is within hydrogen-bonding distance to Ser286 (3.1 Å) and acts as a general base for the nucleophilic attack by accepting the proton from Ser286. Tyr466, which is close to Ser286 and in hydrogen-bonding contact (3.2 Å) with glutamine, is involved in proton transfer during catalysis. Moreover, the carbonyl oxygen of the glutamine is hydrogen-bonded with the main chain amino groups of Ser286 and Val484, forming the oxyanion hole. Thus, we propose that in addition to the putative catalytic dyad (Ser286 XX Lys289), Tyr466 could play an important role in the catalysis (Fig. 1Cand Fig. S2).

http://www.pnas.org/content/109/20/7705/F1.medium.gif

Fig. 1. Schematic view and structure of the cKGA-L-glutamine complex. (A) Human KGA domains and signature motifs (refer to Fig. S1A for details). (B) Structure of the of cKGA and bound substrate (L-glutamine) is shown as a cyan stick. (C) Fourier 2Fo-Fc electron density map (contoured at 1 σ) for L-glutamine, that makes hydrogen bonds with active site residues are shown.

Allosteric Binding Pocket for BPTES. The chemical structure of BPTES has an internal symmetry, with two exactly equivalent parts including a thiadiazole, amide, and a phenyl group (Fig. S3A), and it equally interacts with each monomer. The thiadiazole group and the aliphatic linker are well buried in a hydrophobic cluster that consists of Leu321, Phe322, Leu323, and Tyr394 from both monomers, which forms the allosteric pocket (Fig. 2 B–E). The side chain of Phe322 is found at the bottom of the allosteric pocket. The phenyl-acetamido moiety of BPTES is partially exposed on the loop (Asn324-Glu325), where it interacts with Phe318, Asn324, and the aliphatic part of the Glu325 side chain. On the basis of our observations we synthesized a series of BPTES-derived inhibitors (compounds2–5) (Fig. S3 A–F and SI Results) and solved their cocrystal structure of compounds 2–4. Similar to BPTES, compounds 2–4 all resides within the hydrophobic cluster of the allosteric pocket (Fig. S3 C–F).

Fig. 2. Structure of cKGA: BPTES complex and the allosteric binding mode of BPTES.

Allosteric Binding of BPTES Triggers Major Conformational Change in the Key Loop Near the Active Site. The overall structure of these inhibitor complexes superimposes well with apo cKGA. However, a major conformational change at the Glu312 to Pro329 loop was observed in the BPTES complex (Fig. 2F). The most conformational changes of the backbone atoms that moved away from the active site region are found at the center of the loop (Leu316-Lys320). The backbone of the residues Phe318 and Asn319 is moved ≈9 Å and ≈7 Å, respectively, compared with the apo structure, whereas the side chain of these residues moved ≈14 Å and ≈12 Å, respectively. This loop rearrangement in turn brings Phe318 closer to the phenyl group of the inhibitor and forms the inhibitor binding pocket, whereas in the apo structure the same loop region (Leu316-Lys320) was found to be adjacent to the active site and forms a closed conformation of the active site.

Binding of BPTES Stabilizes the Inactive Tetramers of cKGA. To understand the role of oligomerization in KGA function, dimers and tetramers of cKGA were generated using the symmetry-related monomers (Fig. 2 A–E and Fig. S4 D and E). The dimer interface in the cKGA: BPTES complex is formed by residues from the helix Asp386-Lys398 of both monomers and involves hydrogen bonding, salt bridges, and hydrophobic interactions (Phe389, Ala390, Tyr393, and Tyr394), besides two sulfate ions located in the interface (Fig. 2E). The dimers are further stabilized by binding of BPTES, where it binds to loop residues (Glu312-Pro329) and Tyr394 from both monomers (Fig. 2 D and E). Similarly, residues from Lys311-Asn319 loop and Arg454, His461, Gln471, and Asn529-Leu533 are involved in the interface with neighboring monomers to form the tetramer in the BPTES complex.

BPTES Induces Allosteric Conformational Changes That Destabilize Catalytic Function of KGA

Fig. 3A shows that 293T cells overexpressing KGA produced higher level of glutamate compared with the vector control cells. Most significantly, all of these mutants, except Phe322Ala, greatly diminished the KGA activity.

Fig. 3. Mutations at allosteric loop and BPTES binding pocket abrogate KGA activity and BPTES sensitivity.

Raf-Mek-Erk Signaling Module Regulates KGA Activity. Because KGA supports cell growth and proliferation, we first validated that treatment of cells with BPTES indeed inhibits KGA activity and cell proliferation (Fig. S5 A–D and SI Results). Next, as cells respond to various physiological stimuli to regulate their metabolism, with many of the metabolic enzymes being the primary targets of modulation (18), we examined whether KGA activity can be regulated by physiological stimuli, in particular EGF, which is important for cell growth and proliferation. Cells overexpressing KGA were made quiescent and then stimulated with EGF for various time points. Fig. 4A shows that the basal KGA activity remained unchanged 30 min after EGF stimulation, but the activity was substantially enhanced after 1 h and then gradually returned to the basal level after 4 h. Because EGF activates the Raf-Mek-Erk signaling module (19), treatment of cells with Mek-specific inhibitor U0126 could block the enhanced KGA activity with parallel inhibition of Erk phosphorylation (Fig. 4A). Interestingly, such Mek-induced KGA activity is specific to EGF and lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) but not with other growth factors, such as PDGF, TGF-β, and basic FGF (bFGF), despite activation of Mek-Erk by bFGF (Fig. S6A).

The results show that KGA could interact equally well with the wild-type or mutant forms of Raf-1 and Mek2 (Fig. 4C). Importantly, endogenous Raf-1 or Erk1/2, including the phosphorylated Erk1/2 (Fig. 4 C and D), could be detected in the KGA complex. Taken together, these results indicate that the activity of KGA is directly regulated by Raf-Mek-Erk downstream of EGF receptor. To further show that Mek2-enhanced KGA activity requires both the kinase activity of Mek2 and the core residues for KGA catalysis, wild-type or triple mutant (Leu321Ala/Phe322Ala/Leu323Ala) of KGA was coexpressed with dominant negative Mek2-KA or the constitutive active Mek2-SD and their KGA activities measured. The result shows that the presence of Mek2-KA blocks KGA activity, whereas the triple mutant still remains inert even in the presence of the constitutively active Mek2 (Fig. 4E), and despite Mek2 binding to the KGA triple mutant (Fig. S7B). Consequently, expressing triple mutant did not support cell proliferation as well as the wild-type control (Fig. S7C).

Fig. 4. EGFR-Raf-Mek-Erk signaling stimulates KGA activity.

When cells expressing both KGA and Mek2-K101A were treated with subthreshold levels of BPTES, there was a synergistic reduction in cell proliferation (Fig. S6C and SI Results). Lastly, to determine whether regulation of KGA by Raf-Mek-Erk depends on its phosphorylation status, cells were transfected with KGA with or without the protein phosphatase PP2A and assayed for the KGA activity. PP2A is a ubiquitous and conserved serine/threonine phosphatase with broad substrate specificity. The results indicate that KGA activity was reduced down to the basal level in the presence of PP2A (Fig. 5A). Coimmunoprecipitation study also revealed that KGA interacts with PP2A (Fig. 5B), suggesting a negative feedback regulation by this protein phosphatase. Furthermore, treatment of immunoprecipitated and purified KGA with calf-intestine alkaline phosphatase (CIAP) almost completely abolished the KGA activity in vitro (Fig. S6D). Taken together, these results indicate that KGA activity is regulated by Raf-Mek2, and KGA activation by EGF could be part of the EGF-stimulated Raf-Mek-Erk signaling program in controlling cell growth and proliferation (Fig. 5C).

http://www.pnas.org/content/109/20/7705/F5.medium.gif

Fig. 5. KGA activity is regulated by phosphorylation. (C) Schematic model depicting the synergistic cross-talk between KGA-mediated glutaminolysis and EGF-activated Raf-Mek-Erk signaling. Exogenous glutamine can be transported across the membrane and converted to glutamate by glutaminase (KGA), thus feeding the metabolite to the ATP-producing tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle. This process can be stimulated by EGF receptor-mediated Raf-Mek-Erk signaling via their phosphorylation-dependent pathway, as evidenced by the inhibition of KGA activity by the kinase-dead and dominant negative mutants of Raf-1 (Raf-1-K375M) and Mek2 (Mek2-K101A), protein phosphatase PP2A, and Mek-specific inhibitor U0126. Consequently, inhibiting KGA with BPTES and blocking Raf-Mek pathway with Mek2-K101A provide a synergistic inhibition on cell proliferation.

Small-molecule inhibitors that target glutaminase activity in cancer cells are under development. Earlier efforts targeting glutaminase using glutamine analogs have been unsuccessful owing to their toxicities (2). BPTES has attracted much attention as a selective, nontoxic inhibitor of KGA (15), and preclinical testing of BPTES toward human cancers has just begun (20). BPTES selectively suppresses the growth of glioma cells (21) and inhibits the growth of lymphoma tumor growth in animal model studies (22). Wang et al. (11) reported a small molecule that targets glutaminase activity and oncogenic transformation. Despite extensive studies, nothing is known about the structural and molecular basis for KGA inhibitory mechanisms and how their function is regulated during normal and cancer cell metabolism. Such limited information impedes our effort in producing better generations of inhibitors for better treatment regimens.

Comparison of the complex structures with apo cKGA structure, which has well-defined electron density for the key loop, we provide the atomic view of an allosteric binding pocket for BPTES and elucidate the inhibitory mechanism of KGA by BPTES. The key residues of the loop (Glu312-Pro329) undergo major conformational changes upon binding of BPTES. In addition, structure-based mutagenesis studies suggest that this loop is essential for stabilizing the active site. Therefore, by binding in an allosteric pocket, BPTES inhibits the enzymatic activity of KGA through (i) triggering a major conformational change on the key residues that would normally be involved in stabilizing the active sites and regulating its enzymatic activity; and (ii) forming a stable inactive tetrameric KGA form. Our findings are further supported by two very recent reports on KGA isoform (GAC) (23, 24), although these studies lack full details owing to limitation of their electron density maps. BPTES is specific to KGA but not to LGA (15). Sequence comparison of KGA with LGA (Fig. S8A) reveals two unique residues on KGA, Phe318 and Phe322, which upon mutation to LGA counterparts, become resistant to BPTES. Thus, our study provides the molecular basis of BPTES specificity.

7.7.2 Sonic hedgehog (Shh) signaling promotes tumorigenicity and stemness via activation of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in bladder cancer.

Islam SS, Mokhtari RB, Noman AS, …, van der Kwast T, Yeger H, Farhat WA.

Molec Carcinogenesis mar 2015; 54(5). http://dx.doi.org:/10.1002/mc.22300

Activation of the sonic hedgehog (Shh) signaling pathway controls tumorigenesis in a variety of cancers. Here, we show a role for Shh signaling in the promotion of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), tumorigenicity, and stemness in the bladder cancer. EMT induction was assessed by the decreased expression of E-cadherin and ZO-1 and increased expression of N-cadherin. The induced EMT was associated with increased cell motility, invasiveness, and clonogenicity. These progression relevant behaviors were attenuated by treatment with Hh inhibitors cyclopamine and GDC-0449, and after knockdown by Shh-siRNA, and led to reversal of the EMT phenotype. The results with HTB-9 were confirmed using a second bladder cancer cell line, BFTC905 (DM). In a xenograft mouse model TGF-β1 treated HTB-9 cells exhibited enhanced tumor growth. Although normal bladder epithelial cells could also undergo EMT and upregulate Shh with TGF-β1 they did not exhibit tumorigenicity. The TGF-β1 treated HTB-9 xenografts showed strong evidence for a switch to a more stem cell like phenotype, with functional activation of CD133, Sox2, Nanog, and Oct4. The bladder cancer specific stem cell markers CK5 and CK14 were upregulated in the TGF-β1 treated xenograft tumor samples, while CD44 remained unchanged in both treated and untreated tumors. Immunohistochemical analysis of 22 primary human bladder tumors indicated that Shh expression was positively correlated with tumor grade and stage. Elevated expression of Ki-67, Shh, Gli2, and N-cadherin were observed in the high grade and stage human bladder tumor samples, and conversely, the downregulation of these genes were observed in the low grade and stage tumor samples. Collectively, this study indicates that TGF-β1-induced Shh may regulate EMT and tumorigenicity in bladder cancer. Our studies reveal that the TGF-β1 induction of EMT and Shh is cell type context dependent. Thus, targeting the Shh pathway could be clinically beneficial in the ability to reverse the EMT phenotype of tumor cells and potentially inhibit bladder cancer progression and metastasis

7.7.3 Differential activation of NF-κB signaling is associated with platinum and taxane resistance in MyD88 deficient epithelial ovarian cancer cells

Gaikwad SM, Thakur B, Sakpal A, Singh RK, Ray P.

Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2015 Apr; 61:90-102

http://dx.doi.org:/10.1016/j.biocel.2015.02.001

Development of chemoresistance is a major impediment to successful treatment of patients suffering from epithelial ovarian carcinoma (EOC). Among various molecular factors, presence of MyD88, a component of TLR-4/MyD88 mediated NF-κB signaling in EOC tumors is reported to cause intrinsic paclitaxel resistance and poor survival. However, 50-60% of EOC patients do not express MyD88 and one-third of these patients finally relapses and dies due to disease burden. The status and role of NF-κB signaling in this chemoresistant MyD88(negative) population has not been investigated so far. Using isogenic cellular matrices of cisplatin, paclitaxel and platinum-taxol resistant MyD88(negative) A2780 ovarian cancer cells expressing a NF-κB reporter sensor, we showed that enhanced NF-κB activity was required for cisplatin but not for paclitaxel resistance. Immunofluorescence and gel mobility shift assay demonstrated enhanced nuclear localization of NF-κB and subsequent binding to NF-κB response element in cisplatin resistant cells. The enhanced NF-κB activity was measurable from in vivo tumor xenografts by dual bioluminescence imaging. In contrast, paclitaxel and the platinum-taxol resistant cells showed down regulation in NF-κB activity. Intriguingly, silencing of MyD88 in cisplatin resistant and MyD88(positive) TOV21G and SKOV3 cells showed enhanced NF-κB activity after cisplatin but not after paclitaxel or platinum-taxol treatments. Our data thus suggest that NF-κB signaling is important for maintenance of cisplatin resistance but not for taxol or platinum-taxol resistance in absence of an active TLR-4/MyD88 receptor mediated cell survival pathway in epithelial ovarian carcinoma.

7.7.4 Activation of apoptosis by caspase-3-dependent specific RelB cleavage in anticancer agent-treated cancer cells

Kuboki M, Ito A, Simizu S, Umezawa K.

Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015 Jan 16; 456(3):810-4

http://dx.doi.org:/10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.12.024

Highlights

- We have prepared RelB mutants that are resistant to caspase 3-induced scission.

- Vinblastine induced caspase 3-dependent site-specific RelB cleavage in cancer cells.

- Cancer cells expressing cleavage-resistant RelB showed less sensitivity to vinblastine.

- Caspase 3-induced RelB cleavage may provide positive feedback mechanism in apoptosis.

DTCM-glutarimide (DTCM-G) is a newly found anti-inflammatory agent. In the course of experiments with lymphoma cells, we found that DTCM-G induced specific RelB cleavage. Anticancer agent vinblastine also induced the specific RelB cleavage in human fibrosarcoma HT1080 cells. The site-directed mutagenesis analysis revealed that the Asp205 site in RelB was specifically cleaved possibly by caspase-3 in vinblastine-treated HT1080 cells. Moreover, the cells stably overexpressing RelB Asp205Ala were resistant to vinblastine-induced apoptosis. Thus, the specific Asp205 cleavage of RelB by caspase-3 would be involved in the apoptosis induction by anticancer agents, which would provide the positive feedback mechanism.

7.7.5 Identification of Liver Cancer Progenitors Whose Malignant Progression Depends on Autocrine IL-6 Signaling

He G, Dhar D, Nakagawa H, Font-Burgada J, Ogata H, Jiang Y, et al.

Cell. 2013 Oct 10; 155(2):384-96

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.cell.2013.09.031

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a slowly developing malignancy postulated to evolve from pre-malignant lesions in chronically damaged livers. However, it was never established that premalignant lesions actually contain tumor progenitors that give rise to cancer. Here, we describe isolation and characterization of HCC progenitor cells (HcPCs) from different mouse HCC models. Unlike fully malignant HCC, HcPCs give rise to cancer only when introduced into a liver undergoing chronic damage and compensatory proliferation. Although HcPCs exhibit a similar transcriptomic profile to bipotential hepatobiliary progenitors, the latter do not give rise to tumors. Cells resembling HcPCs reside within dysplastic lesions that appear several months before HCC nodules. Unlike early hepatocarcinogenesis, which depends on paracrine IL-6 production by inflammatory cells, due to upregulation of LIN28 expression, HcPCs had acquired autocrine IL-6 signaling that stimulates their in vivo growth and malignant progression. This may be a general mechanism that drives other IL-6-producing malignancies.

Clonal evolution and selective pressure may cause some descendants of the initial progenitor to cross the bridge of no return and form a premalignant lesion. Cancer genome sequencing indicates that most cancers require at least five genetic changes to evolve (Wood et al., 2007). It has been difficult to isolate and propagate cancer progenitors prior to detection of tumor masses. Further, it is not clear whether cancer progenitors are the precursors for the cancer stem cells (CSCs)isolated from cancers. An answer to these critical questions depends on identification and isolation of cancer progenitors, which may also enable definition of molecular markers and signaling pathways suitable for early detection and treatment.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the end product of chronic liver diseases, requires several decades to evolve (El-Serag, 2011). It is the third most deadly and fifth most common cancer worldwide, and in the United States its incidence has doubled in the past two decades. Furthermore, 8% of the world’s population are chronically infected with hepatitis B or C viruses (HBV and HCV) and are at a high risk of new HCC development (El-Serag, 2011). Up to 5% of HCV patients will develop HCC in their lifetime, and the yearly HCC incidence in patients with cirrhosis is 3%–5%. These tumors may arise from premalignant lesions, ranging from dysplastic foci to dysplastic hepatocyte nodules that are often seen in damaged and cirrhotic livers and are more proliferative than the surrounding parenchyma (Hytiroglou et al., 2007). There is no effective treatment for HCC and, upon diagnosis, most patients with advanced disease have a remaining lifespan of 4–6 months. Premalignant lesions, called foci of altered hepatocytes (FAH), were described in chemically induced HCC models (Pitot, 1990), but it was questioned whether these lesions harbor tumor progenitors or result from compensatory proliferation (Sell and Leffert, 2008). The aim of this study was to determine whether HCC progenitor cells (HcPCs) exist and if so, to isolate these cells and identify some of the signaling networks that are involved in their maintenance and progression.

We now describe HcPC isolation from mice treated with the procarcinogen diethyl nitrosamine (DEN), which induces poorly differentiated HCC nodules within 8 to 9 months (Verna et al., 1996). The use of a chemical carcinogen is justified because the finding of up to 121 mutations per HCC genome suggests that carcinogens may be responsible for human HCC induction (Guichard et al., 2012). Furthermore, 20%–30% of HCC, especially in HBV-infected individuals, evolve in noncirrhotic livers (El-Serag, 2011). Nonetheless, we also isolated HcPCs fromTak1Δhep mice, which develop spontaneous HCC as a result of progressive liver damage, inflammation, and fibrosis caused by ablation of TAK1 (Inokuchi et al., 2010). Although the etiology of each model is distinct, both contain HcPCs that express marker genes and signaling pathways previously identified in human HCC stem cells (Marquardt and Thorgeirsson, 2010) long before visible tumors are detected. Furthermore, DEN-induced premalignant lesions and HcPCs exhibit autocrine IL-6 production that is critical for tumorigenic progression. Circulating IL-6 is a risk indicator in several human pathologies and is strongly correlated with adverse prognosis in HCC and cholangiocarcinoma (Porta et al., 2008; Soresi et al., 2006). IL-6 produced by in-vitro-induced CSCs was suggested to be important for their maintenance (Iliopoulos et al., 2009). Little is known about the source of IL-6 in HCC.

DEN-Induced Collagenase-Resistant Aggregates of HCC Progenitors

A single intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of DEN into 15-day-old BL/6 mice induces HCC nodules first detected 8 to 9 months later. However, hepatocytes prepared from macroscopically normal livers 3 months after DEN administration already contain cells that progress to HCC when transplanted into the permissive liver environment of MUP-uPA mice (He et al., 2010), which express urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA) from a mouse liver-specific major urinary protein (MUP) promoter and undergo chronic liver damage and compensatory proliferation (Rhim et al., 1994). HCC markers such as α fetoprotein (AFP), glypican 3 (Gpc3), and Ly6D, whose expression in mouse liver cancer was reported (Meyer et al., 2003), were upregulated in aggregates from DEN-treated livers, but not in nonaggregated hepatocytes or aggregates from control livers (Figure S1A). Using 70 μm and 40 μm sieves, we separated aggregated from nonaggregated hepatocytes (Figure 1A) and tested their tumorigenic potential by transplantation into MUP-uPA mice (Figure 1B). To facilitate transplantation, the aggregates were mechanically dispersed and suspended in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM). Five months after intrasplenic (i.s.) injection of 104 viable cells, mice receiving cells from aggregates developed about 18 liver tumors per mouse, whereas mice receiving nonaggregated hepatocytes developed less than 1 tumor each (Figure 1B). The tumors exhibited typical trabecular HCC morphology and contained cells that abundantly express AFP (Figure S1B).

Only liver tumors were formed by the transplanted cells. Other organs, including the spleen into which the cells were injected, remained tumor free (Figure 1B), suggesting that HcPCs progress to cancer only in the proper microenvironment. Indeed, no tumors appeared after HcPC transplantation into normal BL/6 mice. But, if BL/6 mice were first treated with retrorsine (a chemical that permanently inhibits hepatocyte proliferation [Laconi et al., 1998]), intrasplenically transplanted with HcPC-containing aggregates, and challenged with CCl4 to induce liver injury and compensatory proliferation (Guo et al., 2002), HCCs readily appeared (Figure 1C). CCl4 omission prevented tumor development. Notably, MUP-uPA or CCl4-treated livers are fragile, rendering direct intrahepatic transplantation difficult. CCl4-induced liver damage, especially within a male liver, generates a microenvironment that drives HcPC proliferation and malignant progression. To examine this point, we transplanted GFP-labeled HcPC-containing aggregates into retrorsine-treated BL/6 mice and examined their ability to proliferate with or without subsequent CCl4 treatment. Indeed, the GFP+ cells formed clusters that grew in size only in CCl4-treated host livers (Figure S1E). Omission of CC14 prevented their expansion.

Because CD44 is expressed by HCC stem cells (Yang et al., 2008; Zhu et al., 2010), we dispersed the aggregates and separated CD44+ from CD44− cells and transplanted both into MUP-uPA mice. Whereas as few as 103 CD44+ cells gave rise to HCCs in 100% of recipients, no tumors were detected after transplantation of CD44− cells (Figure 1E). Remarkably, 50% of recipients developed at least one HCC after receiving as few as 102 CD44+ cells.

HcPC-Containing Aggregates in Tak1Δhep Mice

We applied the same HcPC isolation protocol to Tak1Δhep mice, which develop HCC of different etiology from DEN-induced HCC. Importantly, Tak1Δhep mice develop HCC as a consequence of chronic liver injury and fibrosis without carcinogen or toxicant exposure (Inokuchi et al., 2010). Indeed, whole-tumor exome sequencing revealed that DEN-induced HCC contained about 24 mutations per 106 bases (Mb) sequenced, with B-RafV637E being the most recurrent, whereas 1.4 mutations per Mb were detected inTak1Δhep HCC’s exome (Table S1). By contrast, Tak1Δhep HCC exhibited gene copy number changes. HCC developed in 75% of MUP-uPA mice that received dispersed Tak1Δhep aggregates, but no tumors appeared in mice receiving nonaggregated Tak1Δhep or totalTak1f/f hepatocytes (Figure 2B). bile duct ligation (BDL) or feeding with 3,5-dicarbethoxy-1,4-dihydrocollidine (DDC), treatments that cause cholestatic liver injuries and oval cell expansion (Dorrell et al., 2011), did increase the number of small hepatocytic cell aggregates (Figure S2A). Nonetheless, no tumors were observed 5 months after injection of such aggregates into MUP-uPA mice (Figure S2B). Thus, not all hepatocytic aggregates contain HcPCs, and HcPCs only appear under tumorigenic conditions.

The HcPC Transcriptome Is Similar to that of HCC and Oval Cells

To determine the relationship between DEN-induced HcPCs, normal hepatocytes, and fully transformed HCC cells, we analyzed the transcriptomes of aggregated and nonaggregated hepatocytes from male littermates 5 months after DEN administration, HCC epithelial cells from DEN-induced tumors, and normal hepatocytes from age- and gender-matched littermate controls. Clustering analysis distinguished the HCC samples from other samples and revealed that the aggregated hepatocyte samples did not cluster with each other but rather with nonaggregated hepatocytes derived from the same mouse (Figure S3A). 57% (583/1,020) of genes differentially expressed in aggregated relative to nonaggregated hepatocytes are also differentially expressed in HCC relative to normal hepatocytes (Figure 3B, top), a value that is highly significant (p < 7.13 × 10−243). More specifically, 85% (494/583) of these genes are overexpressed in both HCC and HcPC-containing aggregates (Figure 3B, bottom table). Thus, hepatocyte aggregates isolated 5 months after DEN injection contain cells that are related in their gene expression profile to HCC cells isolated from fully developed tumor nodules.

Figure 3 Aggregated Hepatocytes Exhibit an Altered Transcriptome Similar to that of HCC Cells

We examined which biological processes or cellular compartments were significantly overrepresented in the induced or repressed genes in both pairwise comparisons (Gene Ontology Analysis). As expected, processes and compartments that were enriched in aggregated hepatocytes relative to nonaggregated hepatocytes were almost identical to those that were enriched in HCC relative to normal hepatocytes (Figure 3C). Several human HCC markers, including AFP, Gpc3 and H19, were upregulated in aggregated hepatocytes (Figures 3D and 3E). Aggregated hepatocytes also expressed more Tetraspanin 8 (Tspan8), a cell-surface glycoprotein that complexes with integrins and is overexpressed in human carcinomas (Zöller, 2009). Another cell-surface molecule highly expressed in aggregated cells is Ly6D (Figures 3D and 3E). Immunofluorescence (IF) analysis revealed that Ly6D was undetectable in normal liver but was elevated in FAH and ubiquitously expressed in most HCC cells (Figure S3C). A fluorescent-labeled Ly6D antibody injected into HCC-bearing mice specifically stained tumor nodules (Figure S3D). Other cell-surface molecules that were upregulated in aggregated cells included syndecan 3 (Sdc3), integrin α 9 (Itga9), claudin 5 (Cldn5), and cadherin 5 (Cdh5) (Figure 3D). Aggregated hepatocytes also exhibited elevated expression of extracellular matrix proteins (TIF3 and Reln1) and a serine protease inhibitor (Spink3). Elevated expression of such proteins may explain aggregate formation. Aggregated hepatocytes also expressed progenitor cell markers, including the epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM) (Figure 3E) and Dlk1 (Figure 3D). We compared the HcPC and HCC (Figure 3A) to the transcriptome of DDC-induced oval cells (Shin et al., 2011). This analysis revealed a striking similarity between the HCC, HcPC, and the oval cell transcriptomes (Figure S3B). Despite these similarities, some genes that were upregulated in HcPC-containing aggregates and HCC were not upregulated in oval cells. Such genes may account for the tumorigenic properties of HcPC and HCC.

Figure 4 DEN-Induced HcPC Aggregates Express Pathways and Markers Characteristic of HCC and Hepatobiliary Stem Cells

We examined the aggregates for signaling pathways and transcription factors involved in hepatocarcinogenesis. Many aggregated cells were positive for phosphorylated c-Jun and STAT3 (Figure 4A), transcription factors involved in DEN-induced hepatocarcinogenesis (Eferl et al., 2003; He et al., 2010). Sox9, a transcription factor that marks hepatobiliary progenitors (Dorrell et al., 2011), was also expressed by many of the aggregated cells, which were also positive for phosphorylated c-Met (Figure 4A), a receptor tyrosine kinase that is activated by hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) and is essential for liver development (Bladt et al., 1995) and hepatocarcinogenesis (Wang et al., 2001). Few of the nonaggregated hepatocytes exhibited activation of these signaling pathways. Despite different etiology, HcPC-containing aggregates from Tak1Δhep mice exhibit upregulation of many of the same markers and pathways that are upregulated in DEN-induced HcPC-containing aggregates. Flow cytometry confirmed enrichment of CD44+ cells as well as CD44+/CD90+ and CD44+/EpCAM+ double-positive cells in the HcPC-containing aggregates from either DEN-treated or Tak1Δhep livers (Figure S4B).

HcPC-Containing Aggregates Originate from Premalignant Dysplastic Lesions

FAH are dysplastic lesions occurring in rodent livers exposed to hepatic carcinogens (Su et al., 1990). Similar lesions are present in premalignant human livers (Su et al., 1997). Yet, it is still debated whether FAH correspond to premalignant lesions or are a reaction to liver injury that does not lead to cancer (Sell and Leffert, 2008). In DEN-treated males, FAH were detected as early as 3 months after DEN administration (Figure 5A), concomitant with the time at which HcPC-containing aggregates were detected. In females, FAH development was delayed. FAH contained cells positive for the same progenitor cell markers and activated signaling pathways present in HcPC-containing aggregates, including AFP, CD44, and EpCAM (Figure 5C). FAH also contained cells positive for activated STAT3, c-Jun, and PCNA (Figure 5C).

HcPCs Exhibit Autocrine IL-6 Expression Necessary for HCC Progression

In situ hybridization (ISH) and immunohistochemistry (IHC) revealed that DEN-induced FAH contained IL-6-expressing cells (Figures 6A, 6B, and S5), and freshly isolated DEN-induced aggregates contained more IL-6 messenger RNA (mRNA) than nonaggregated hepatocytes (Figure 6C). We examined several factors that control IL-6 expression and found that LIN28A and B were significantly upregulated in HcPCs and HCC (Figures 6D and 6E). LIN28-expressing cells were also detected within FAH (Figure 6F). As reported (Iliopoulos et al., 2009), knockdown of LIN28B in cultured HcPC or HCC cell lines decreased IL-6 expression (Figure 6G). LIN28 exerts its effects through downregulation of the microRNA (miRNA) Let-7 (Iliopoulos et al., 2009).

Figure 6 Liver Premalignant Lesions and HcPCs Exhibit Elevated IL-6 and LIN28 Expression

Figure 7 HCC Growth Depends on Autocrine IL-6 Production

The isolation and characterization of cells that can give rise to HCC only after transplantation into an appropriate host liver undergoing chronic injury demonstrates that cancer arises from progenitor cells that are yet to become fully malignant. Importantly, unlike fully malignant HCC cells, the HcPCs we isolated cannot form s.c. tumors or even liver tumors when introduced into a nondamaged liver. Liver damage induced by uPA expression or CCl4 treatment provides HcPCs with the proper cytokine and growth factor milieu needed for their proliferation. Although HcPCs produce IL-6, they may also depend on other cytokines such as TNF, which is produced by macrophages that are recruited to the damaged liver. In addition, uPA expression and CCl4 treatment may enhance HcPC growth and progression through their fibrogenic effect on hepatic stellate cells. Although HCC and other cancers have been suspected to arise from premalignant/dysplastic lesions (Hruban et al., 2007; Hytiroglou et al., 2007), a direct demonstration that such lesions progress into malignant tumors has been lacking. Based on expression of common markers—EpCAM, CD44, AFP, activated STAT3, and IL-6—that are not expressed in normal hepatocytes, we postulate that HcPCs originate from FAH or dysplastic foci, which are first observed in male mice within 3 months of DEN exposure.

7.7.6 Acetylation Stabilizes ATP-Citrate Lyase to Promote Lipid Biosynthesis and Tumor Growth

Lin R1, Tao R, Gao X, Li T, Zhou X, Guan KL, Xiong Y, Lei QY.

Mol Cell. 2013 Aug 22; 51(4):506-18

http://dx.doi.org:/10.1016/j.molcel.2013.07.002

Increased fatty acid synthesis is required to meet the demand for membrane expansion of rapidly growing cells. ATP-citrate lyase (ACLY) is upregulated or activated in several types of cancer, and inhibition of ACLY arrests proliferation of cancer cells. Here we show that ACLY is acetylated at lysine residues 540, 546, and 554 (3K). Acetylation at these three lysine residues is stimulated by P300/calcium-binding protein (CBP)-associated factor (PCAF) acetyltransferase under high glucose and increases ACLY stability by blocking its ubiquitylation and degradation. Conversely, the protein deacetylase sirtuin 2 (SIRT2) deacetylates and destabilizes ACLY. Substitution of 3K abolishes ACLY ubiquitylation and promotes de novo lipid synthesis, cell proliferation, and tumor growth. Importantly, 3K acetylation of ACLY is increased in human lung cancers. Our study reveals a crosstalk between acetylation and ubiquitylation by competing for the same lysine residues in the regulation of fatty acid synthesis and cell growth in response to glucose.

Fatty acid synthesis occurs at low rates in most nondividing cells of normal tissues that primarily uptake lipids from circulation. In contrast, increased lipogenesis, especially de novo lipid synthesis, is a key characteristic of cancer cells. Many studies have demonstrated that in cancer cells, fatty acids are preferred to be derived from de novo synthesis instead of extracellular lipid supply (Medes et al., 1953; Menendez and Lupu, 2007;Ookhtens et al., 1984; Sabine et al., 1967). Fatty acids are key building blocks for membrane biogenesis, and glucose serves as a major carbon source for de novo fatty acid synthesis (Kuhajda, 2000; McAndrew, 1986;Swinnen et al., 2006). In rapidly proliferating cells, citrate generated by the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, either from glucose by glycolysis or glutamine by anaplerosis, is preferentially exported from mitochondria to cytosol and then cleaved by ATP citrate lyase (ACLY) (Icard et al., 2012) to produce cytosolic acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA), which is the building block for de novo lipid synthesis. As such, ACLY couples energy metabolism with fatty acids synthesis and plays a critical role in supporting cell growth. The function of ACLY in cell growth is supported by the observation that inhibition of ACLY by chemical inhibitors or RNAi dramatically suppresses tumor cell proliferation and induces differentiation in vitro and in vivo (Bauer et al., 2005; Hatzivassiliou et al., 2005). In addition, ACLY activity may link metabolic status to histone acetylation by providing acetyl-CoA and, therefore, gene expression (Wellen et al., 2009).

While ACLY is transcriptionally regulated by sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 (SREBP-1) (Kim et al., 2010), ACLY activity is regulated by the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt pathway (Berwick et al., 2002; Migita et al., 2008; Pierce et al., 1982). Akt can directly phosphorylate and activate ACLY (Bauer et al., 2005; Berwick et al., 2002; Migita et al., 2008; Potapova et al., 2000). Covalent lysine acetylation has recently been found to play a broad and critical role in the regulation of multiple metabolic enzymes (Choudhary et al., 2009; Zhao et al., 2010). In this study, we demonstrate that ACLY protein is acetylated on multiple lysine residues in response to high glucose. Acetylation of ACLY blocks its ubiquitinylation and degradation, thus leading to ACLY accumulation and increased fatty acid synthesis. Our observations reveal a crosstalk between protein acetylation and ubiquitylation in the regulation of fatty acid synthesis and cell growth.

Acetylation of ACLY at Lysines 540, 546, and 554

Recent mass spectrometry-based proteomic analyses have potentially identified a large number of acetylated proteins, including ACLY (Figure S1A available online; Choudhary et al., 2009, Zhao et al., 2010). We detected the acetylation level of ectopically expressed ACLY followed by western blot using pan-specific anti-acetylated lysine antibody. ACLY was indeed acetylated, and its acetylation was increased by nearly 3-fold after treatment with nicotinamide (NAM), an inhibitor of the SIRT family deacetylases, and trichostatin A (TSA), an inhibitor of histone deacetylase (HDAC) class I and class II (Figure 1A). Experiments with endogenous ACLY also showed that TSA and NAM treatment enhanced ACLY acetylation (Figure 1B).

Figure 1 ACLY Is Acetylated at Lysines 540, 546, and 554

Ten putative acetylation sites were identified by mass spectrometry analyses (Table S1). We singly mutated each lysine to either a glutamine (Q) or an arginine (R) and found that no single mutation resulted in a significant reduction of ACLY acetylation (data not shown), indicating that ACLY may be acetylated at multiple lysine residues. Three lysine residues, K540, K546, and K554, received high scores in the acetylation proteomic screen and are evolutionarily conserved from C. elegans to mammals (Figure S1A). We generated triple Q and R mutants of K540, K546, and K554 (3KQ and 3KR) and found that both 3KQ and 3KR mutations resulted in a significant (~60%) decrease in ACLY acetylation (Figure 1C), indicating that 3K are the major acetylation sites of ACLY. Further, we found that the acetylation of endogenous ACLY is clearly increased after treatment of cells with NAM and TSA (Figure 1D). These results demonstrate that ACLY is acetylated at K540, K546, and K554.

Glucose Promotes ACLY Acetylation to Stabilize ACLY

In mammalian cells, glucose is the main carbon source for de novo lipid synthesis. We found that ACLY levels increased with increasing glucose concentration, which also correlated with increased ACLY 3K acetylation (Figure 1E). Furthermore, to confirm whether the glucose level affects ACLY protein stability in vivo, we intraperitoneally injected glucose in BALB/c mice and found that high glucose resulted in a significant increase of ACLY protein levels (Figure 1F).

To determine whether ACLY acetylation affects its protein levels, we treated HeLa and Chang liver cells with NAM and TSA and found an increase in ACLY protein levels (Figure S1G, upper panel). ACLY mRNA levels were not significantly changed by the treatment of NAM and TSA (Figure S1G, lower panel), indicating that this upregulation of ACLY is mostly achieved at the posttranscriptional level. Indeed, ACLY protein was also accumulated in cells treated with the proteasome inhibitor MG132, indicating that ACLY stability could be regulated by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway (Figure 1G). Blocking deacetylase activity stabilized ACLY (Figure S1H). The stabilization of ACLY induced by high glucose was associated with an increase of ACLY acetylation at K540, K546, and K554. Together, these data support a notion that high glucose induces both ACLY acetylation and protein stabilization and prompted us to ask whether acetylation directly regulates ACLY stability. We then generated ACLYWT, ACLY3KQ, and ACLY3KRstable cells after knocking down the endogenous ACLY. We found that the ACLY3KR or ACLY3KQmutant was more stable than the ACLYWT (Figures 1I and S1I). Collectively, our results suggest that glucose induces acetylation at K540, 546, and 554 to stabilize ACLY.

Acetylation Stabilizes ACLY by Inhibiting Ubiquitylation

To determine the mechanism underlying the acetylation and ACLY protein stability, we first examined ACLY ubiquitylation and found that it was actively ubiquitylated (Figure 2A). Previous proteomic analyses have identified K546 in ACLY as a ubiquitylation site (Wagner et al., 2011). In order to identify the ubiquitylation sites, we tested the ubiquitylation levels of double mutants 540R–546R and 546–554R (Figure S2A). We found that the ubiquitylation of the 540R-546R and 546R-554R mutants is partially decreased, while mutation of K540, K546, and K554 (3KR), which changes all three putative acetylation lysine residues of ACLY to arginine residues, dramatically reduced the ACLY ubiquitylation level (Figures 2B and S2A), indicating that 3K lysines might also be the ubiquitylation target residues. Moreover, inhibition of deacetylases by NAM and TSA decreased ubiquitylation of WT but not 3KQ or 3KR mutant ACLY (Figure 2C). These results implicate an antagonizing role of the acetylation towards the ubiquitylation of ACLY at these three lysine residues.

Figure 2 Acetylation Protects ACLY from Proteasome Degradation by Inhibiting Ubiquitylation

We found that ACLY acetylation was only detected in the nonubiquitylated, but not the ubiquitylated (high-molecular-weight), ACLY species. This result indicates that ACLY acetylation and ubiquitylation are mutually exclusive and is consistent with the model that K540, K546, and K554 are the sites of both ubiquitylation and acetylation. Therefore, acetylation of these lysines would block ubiquitylation.

We also found that glucose upregulates ACLY acetylation at 3K and decreases its ubiquitylation (Figure S2B). High glucose (25 mM) effectively decreased ACLY ubiquitylation, while inhibition of deacetylases clearly diminished its ubiquitylation (Figure 2E). We conclude that acetylation and ubiquitylation occur mutually exclusively at K540, K546, and K554 and that high-glucose-induced acetylation at these three sites blocks ACLY ubiquitylation and degradation.

UBR4 Targets ACLY for Degradation

UBR4 was identified as a putative ACLY-interacting protein by affinity purification coupled with mass spectrometry analysis (data not shown). To address if UBR4 is a potential ACLY E3 ligase, we determined the interaction between ACLY and UBR4 and found that ACLY interacted with the E3 ligase domain of UBR4; this interaction was enhanced by MG132 treatment (Figure 3A). UBR4 knockdown in A549 cells resulted in an increase of endogenous ACLY protein level (Figure 3C). Moreover, UBR4 knockdown significantly stabilized ACLY (Figure 3D) and decreased ACLY ubiquitylation (Figure 3E). Taken together, these results indicate that UBR4 is an ACLY E3 ligase that responds to glucose regulation.

Figure 3 UBR4 Is the E3 Ligase of ACLY

PCAF Acetylates ACLY

PCAF knockdown significantly reduced acetylation of 3K, indicating that PCAF is a potential 3K acetyltransferase in vivo (Figure 4C, upper panel). Furthermore, PCAF knockdown decreased the steady-state level of endogenous ACLY, but not ACLY mRNA (Figure 4C, middle and lower panels). Moreover, we found that PCAF knockdown destabilized ACLY (Figure 4D). In addition, overexpression of PCAF decreases ACLY ubiquitylation (Figure 4E), while PCAF inhibition increases the interaction between UBR4 E3 ligase domain and wild-type ACLY, but not 3KR (Figure 4F). Together, our results indicate that PCAF increases ACLY protein level, possibly via acetylating ACLY at 3K.

Figure 4 PCAF Is the Acetylase of ACLY

SIRT2 Deacetylates ACLY

Figure 5 SIRT2 Decreases ACLY Acetylation and Increases Its Protein Levels In Vivo

Acetylation of ACLY Promotes Cell Proliferation and De Novo Lipid Synthesis

The protein levels of ACLY 3KQ and 3KR were accumulated to a level higher than the wild-type cells upon extended culture in low-glucose medium (Figure S6A, right panel), indicating a growth advantage conferred by ACLY stabilization resulting from the disruption of both acetylation and ubiquitylation at K540, K546, and K554. Cellular acetyl-CoA assay showed that cells expressing 3KQ or 3KR mutant ACLY produce more acetyl-CoA than cells expressing the wild-type ACLY under low glucose (Figures 6B and S6B), further supporting the conclusion that 3KQ or 3KR mutation stabilizes ACLY.

Figure 6 Acetylation of ACLY at 3K Promotes Lipogenesis and Tumor Cell Proliferation

ACLY is a key enzyme in de novo lipid synthesis. Silencing ACLY inhibited the proliferation of multiple cancer cell lines, and this inhibition can be partially rescued by adding extra fatty acids or cholesterol into the culture media (Zaidi et al., 2012). This prompted us to measure extracellular lipid incorporation in A549 cells after knockdown and ectopic expression of ACLY. We found that when cultured in low glucose (2.5 mM), cells expressing wild-type ACLY uptake significantly more phospholipids compared to cells expressing 3KQ or 3KR mutant ACLY (Figures 6C, 6D, and S6D). When cultured in the presence of high glucose (25 mM), however, cells expressing either the wild-type, 3KQ, or 3KR mutant ACLY all have reduced, but similar, uptake of extracellular phospholipids (Figures 6C, 6D, and S6D). The above results are consistent with a model that acetylation of ACLY induced by high glucose increases its stability and stimulates de novo lipid synthesis.

3K Acetylation of ACLY Is Increased in Lung Cancer

ACLY is reported to be upregulated in human lung cancer (Migita et al., 2008). Many small chemicals targeting ACLY have been designed for cancer treatment (Zu et al., 2012). The finding that 3KQ or 3KR mutant increased the ability of ACLY to support A549 lung cancer cell proliferation prompted us to examine 3K acetylation in human lung cancers. We collected a total of 54 pairs of primary human lung cancer samples with adjacent normal lung tissues and performed immunoblotting for ACLY protein levels. This analysis revealed that, when compared to the matched normal lung tissues, 29 pairs showed a significant increase of total ACLY protein using b-actin as a loading control (Figures 7A and S7A). The tumor sample analyses demonstrate that ACLY protein levels are elevated in lung cancers, and 3K acetylation positively correlates with the elevated ACLY protein. These data also indicate that ACLY with 3K acetylation may be potential biomarker for lung cancer diagnosis.

Figure 7 Acetylation of ACLY at 3K Is Upregulated in Human Lung Carcinoma

Dysregulation of cellular metabolism is a hallmark of cancer (Hanahan and Weinberg, 2011; Vander Heiden et al., 2009). Besides elevated glycolysis, increased lipogenesis, especially de novo lipid synthesis, also plays an important role in tumor growth. Because most carbon sources for fatty acid synthesis are from glucose in mammalian cells (Wellen et al., 2009), the channeling of carbon into de novo lipid synthesis as building blocks for tumor cell growth is primarily linked to acetyl-CoA production by ACLY. Moreover, the ACLY-catalyzed reaction consumes ATP. Therefore, as the key cellular energy and carbon source, one may expect a role for glucose in ACLY regulation. In the present study, we have uncovered a mechanism of ACLY regulation by glucose that increases ACLY protein level to meet the enhanced demand of lipogenesis in growing cells, such as tumor cells (Figure 7C). Glucose increases ACLY protein levels by stimulating its acetylation.

Upregulation of ACLY is common in many cancers (Kuhajda, 2000; Milgraum et al., 1997; Swinnen et al., 2004; Yahagi et al., 2005). This is in part due to the transcriptional activation by SREBP-1 resulting from the activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway in cancers (Kim et al., 2010; Nadler et al., 2001; Wang and Dey, 2006). In this study, we report a mechanism of ACLY regulation at the posttranscriptional level. We propose that acetylation modulated by glucose status plays a crucial role in coordinating the intracellular level of ACLY, hence fatty acid synthesis, and glucose availability. When glucose is sufficient, lipogenesis is enhanced. This can be achieved, at least in part, by the glucose-induced stabilization of ACLY. High glucose increases ACLY acetylation, which inhibits its ubiquitylation and degradation, leading to the accumulation of ACLY and enhanced lipogenesis. In contrast, when glucose is limited, ACLY is not acetylated and thus can be ubiquitylated, leading to ACLY degradation and reduced lipogenesis. Moreover, our data indicate that acetylation and ubiquitylation in ACLY may compete with each other by targeting the same lysine residues at K540, K546, and K554. Consistently, previous proteomic analyses have identified K546 in ACLY as a ubiquitylation site (Wagner et al., 2011). Similar models of different modifications on the same lysine residues have been reported in the regulation of other proteins (Grönroos et al., 2002; Li et al., 2002, 2012). We propose that acetylation and ubiquitylation have opposing effects in the regulation of ACLY by competitively modifying the same lysine residues. The acetylation-mimetic 3KQ and the acetylation-deficient 3KR mutants behaved indistinguishably in most biochemical and functional assays, mainly due to the fact that these mutations disrupt lysine ubiquitylation that primarily occurs on these three residues.

ACLY is increased in lung cancer tissues compared to adjacent tissues. Consistently, ACLY acetylation at 3K is also significantly increased in lung cancer tissues. These observations not only confirm ACLY acetylation in vivo, but also suggest that ACLY 3K acetylation may play a role in lung cancer development. Our study reveals a mechanism of ACLY regulation in response to glucose signals.

7.7.7 Monoacylglycerol Lipase Regulates a Fatty Acid Network that Promotes Cancer Pathogenesis

Nomura DK1, Long JZ, Niessen S, Hoover HS, Ng SW, Cravatt BF.

Cell. 2010 Jan 8; 140(1):49-61

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016.2Fj.cell.2009.11.027

Highlights

- Monoacylglycerol lipase (MAGL) is elevated in aggressive human cancer cells

- Loss of MAGL lowers fatty acid levels in cancer cells and impairs pathogenicity

- MAGL controls a signaling network enriched in protumorigenic lipids

- A high-fat diet can restore the growth of tumors lacking MAGL in vivo

http://www.cell.com/cms/attachment/1082768/7977146/fx1.jpg

Tumor cells display progressive changes in metabolism that correlate with malignancy, including development of a lipogenic phenotype. How stored fats are liberated and remodeled to support cancer pathogenesis, however, remains unknown. Here, we show that the enzyme monoacylglycerol lipase (MAGL) is highly expressed in aggressive human cancer cells and primary tumors, where it regulates a fatty acid network enriched in oncogenic signaling lipids that promotes migration, invasion, survival, and in vivo tumor growth. Overexpression of MAGL in nonaggressive cancer cells recapitulates this fatty acid network and increases their pathogenicity—phenotypes that are reversed by an MAGL inhibitor. Impairments in MAGL-dependent tumor growth are rescued by a high-fat diet, indicating that exogenous sources of fatty acids can contribute to malignancy in cancers lacking MAGL activity. Together, these findings reveal how cancer cells can co-opt a lipolytic enzyme to translate their lipogenic state into an array of protumorigenic signals.

We show that the enzyme monoacylglycerol lipase (MAGL) is highly expressed in aggressive human cancer cells and primary tumors, where it regulates a fatty acid network enriched in oncogenic signaling lipids that promotes migration, invasion, survival, and in vivo tumor growth. Overexpression of MAGL in non-aggressive cancer cells recapitulates this fatty acid network and increases their pathogenicity — phenotypes that are reversed by an MAGL inhibitor. Interestingly, impairments in MAGL-dependent tumor growth are rescued by a high-fat diet, indicating that exogenous sources of fatty acids can contribute to malignancy in cancers lacking MAGL activity. Together, these findings reveal how cancer cells can co-opt a lipolytic enzyme to translate their lipogenic state into an array of pro-tumorigenic signals.

The conversion of cells from a normal to cancerous state is accompanied by reprogramming of metabolic pathways (Deberardinis et al., 2008; Jones and Thompson, 2009; Kroemer and Pouyssegur, 2008), including those that regulate glycolysis (Christofk et al., 2008; Gatenby and Gillies, 2004), glutamine-dependent anaplerosis (DeBerardinis et al., 2008; DeBerardinis et al., 2007; Wise et al., 2008), and the production of lipids (DeBerardinis et al., 2008; Menendez and Lupu, 2007). Despite a growing appreciation that dysregulated metabolism is a defining feature of cancer, it remains unclear, in many instances, how such biochemical changes occur and whether they play crucial roles in disease progression and malignancy.

Among dysregulated metabolic pathways, heightened de novo lipid biosynthesis, or the development a “lipogenic” phenotype (Menendez and Lupu, 2007), has been posited to play a major role in cancer. For instance, elevated levels of fatty acid synthase (FAS), the enzyme responsible for fatty acid biosynthesis from acetate and malonyl CoA, are correlated with poor prognosis in breast cancer patients, and inhibition of FAS results in decreased cell proliferation, loss of cell viability, and decreased tumor growth in vivo (Kuhajda et al., 2000; Menendez and Lupu, 2007; Zhou et al., 2007). FAS may support cancer growth, at least in part, by providing metabolic substrates for energy production (via fatty acid oxidation) (Buzzai et al., 2005; Buzzai et al., 2007; Liu, 2006). Many other features of lipid biochemistry, however, are also critical for supporting the malignancy of cancer cells, including:

- the generation of building blocks for newly synthesized membranes to accommodate high rates of proliferation (DeBerardinis et al., 2008; Deberardinis et al., 2008),

- the composition and regulation of membrane structures that coordinate signal transduction and motility [e.g., lipid rafts (Gao and Zhang, 2008), invadopodia (Stylli et al., 2008), blebs (Fackler and Grosse, 2008)] and

- the biosynthesis of an array of pro-tumorigenic lipid signaling molecules.

Prominent examples of lipid messengers that contribute to cancer include:

- phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate [PI(3,4,5)P3], which is formed by the action of phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase and activates protein kinase B/Akt to promote cell proliferation and survival (Yuan and Cantley, 2008; Zunder et al., 2008);

- lysophosphatidic acid (LPA), which signals through a family of G-protein coupled receptors to stimulate cancer aggressiveness (Mills and Moolenaar, 2003; Ren et al., 2006); and

- prostaglandins formed by cyclooxygenases, which support migration and tumor-host interactions (Gupta et al., 2007; Marnett, 1992).

Here, we use functional proteomic methods to discover a lipolytic enzyme, monoacylglycerol lipase (MAGL), that is highly elevated in aggressive cancer cells from multiple tissues of origin. We show that MAGL, through hydrolysis of monoacylglycerols (MAGs), controls free fatty acid (FFA) levels in cancer cells. The resulting MAGL-FFA pathway feeds into a diverse lipid network enriched in pro-tumorigenic signaling molecules and promotes migration, survival, and in vivo tumor growth. Aggressive cancer cells thus pair lipogenesis with high lipolytic activity to generate an array of pro-tumorigenic signals that support their malignant behavior.

Activity-Based Proteomic Analysis of Hydrolytic Enzymes in Human Cancer Cells

To identify enzyme activities that contribute to cancer pathogenesis, we conducted a functional proteomic analysis of a panel of aggressive and non-aggressive human cancer cell lines from multiple tumors of origin, including melanoma [aggressive (C8161, MUM2B), non-aggressive (MUM2C)], ovarian [aggressive (SKOV3), non-aggressive (OVCAR3)], and breast [aggressive (231MFP), non-aggressive (MCF7)] cancer. Aggressive cancer lines were confirmed to display much greater in vitro migration and in vivo tumor-growth rates compared to their non-aggressive counterparts (Figure S1), as previously shown (Jessani et al., 2004;Jessani et al., 2002; Seftor et al., 2002; Welch et al., 1991). Proteomes from these cancer lines were screened by activity-based protein profiling (ABPP) using serine hydrolase-directed fluorophosphonate (FP) activity-based probes (Jessani et al., 2002; Patricelli et al., 2001). Serine hydrolases are one of the largest and most diverse enzyme classes in the human proteome (representing ~ 1–1.5% of all human proteins) and play important roles in many biochemical processes of potential relevance to cancer, such as proteolysis (McMahon and Kwaan, 2008; Puustinen et al., 2009), signal transduction (Puustinen et al., 2009), and lipid metabolism (Menendez and Lupu, 2007; Zechner et al., 2005). The goal of this study was to identify hydrolytic enzyme activities that were consistently altered in aggressive versus non-aggressive cancer lines, working under the hypothesis that these conserved enzymatic changes would have a high probability of contributing to the pathogenic state of cancer cells.

Among the more than 50 serine hydrolases detected in this analysis (Tables S1–3), two enzymes, KIAA1363 and MAGL, were found to be consistently elevated in aggressive cancer cells relative to their non-aggressive counterparts, as judged by spectral counting (Jessani et al., 2005; Liu et al., 2004). We confirmed elevations in KIAA1363 and MAGL in aggressive cancer cells by gel-based ABPP, where proteomes are treated with a rhodamine-tagged FP probe and resolved by 1D-SDS-PAGE and in-gel fluorescence scanning (Figure 1A). In both cases, two forms of each enzyme were detected (Figure 1A), due to differential glycoslyation for KIAA1363 (Jessani et al., 2002), and possibly alternative splicing for MAGL (Karlsson et al., 2001). We have previously shown that KIAA1363 plays a role in regulating ether lipid signaling pathways in aggressive cancer cells (Chiang et al., 2006). On the other hand, very little was known about the function of MAGL in cancer.

Figure 1 MAGL is elevated in aggressive cancer cells, where the enzyme regulates monoacylgycerol (MAG) and free fatty acid (FFA) levels

The heightened activity of MAGL in aggressive cancer cells was confirmed using the substrate C20:4 MAG (Figure 1B). Since several enzymes have been shown to display MAG hydrolytic activity (Blankman et al., 2007), we confirmed the contribution that MAGL makes to this process in cancer cells using the potent and selective MAGL inhibitor JZL184 (Long et al., 2009a).

MAGL Regulates Free Fatty Acid Levels in Aggressive Cancer Cells

MAGL is perhaps best recognized for its role in degrading the endogenous cannabinoid 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG, C20:4 MAG), as well as other MAGs, in brain and peripheral tissues (Dinh et al., 2002; Long et al., 2009a; Long et al., 2009b; Nomura et al., 2008). Consistent with this established function, blockade of MAGL by JZL184 (1 μM, 4 hr) produced significant elevations in the levels of several MAGs, including 2-AG, in each of the aggressive cancer cell lines (Figure 1C and Figure S2). Interestingly, however, MAGL inhibition also caused significant reductions in the levels of FFAs in aggressive cancer cells (Figure 1D and Figure S2). This surprising finding contrasts with the function of MAGL in normal tissues, where the enzyme does not, in general, control the levels of FFAs (Long et al., 2009a; Long et al., 2009b;Nomura et al., 2008).

Metabolic labeling studies using the non-natural C17:0-MAG confirmed that MAGs are converted to LPC and LPE by aggressive cancer cells, and that this metabolic transformation is significantly enhanced by treatment with JZL184 (Figure S1). Finally, JZL184 treatment did not affect the levels of MAGs and FFAs in non-aggressive cancer lines (Figure 1C, D), consistent with the negligible expression of MAGL in these cells (Figure 1A, B).

We next stably knocked down MAGL expression by RNA interference technology using two independent shRNA probes (shMAGL1, shMAGL2), both of which reduced MAGL activity by 70–80% in aggressive cancer lines (Figure 2A, D and Figure S2). Other serine hydrolase activities were unaffected by shMAGL probes (Figure 2A, D and Figures S2), confirming the specificity of these reagents. Both shMAGL probes caused significant elevations in MAGs and corresponding reductions in FFAs in aggressive melanoma (Figure 2B, C), ovarian (Figure 2E, F), and breast cancer cells (Figure S2).

Figure 2 Stable shRNA-mediated knockdown of MAGL lowers FFA levels in aggressive cancer cells.

Together, these data demonstrate that both acute (pharmacological) and stable (shRNA) blockade of MAGL cause elevations in MAGs and reductions in FFAs in aggressive cancer cells. These intriguing findings indicate that MAGL is the principal regulator of FFA levels in aggressive cancer cells. Finally, we confirmed that MAGL activity (Figure 3A, B) and FFA levels (Figure 3C) are also elevated in high-grade primary human ovarian tumors compared to benign or low-grade tumors. Thus, heightened expression of the MAGL-FFA pathway is a prominent feature of both aggressive human cancer cell lines and primary tumors.

Figure 3 High-grade primary human ovarian tumors possess elevated MAGL activity and FFAs compared to benign tumors.

Disruption of MAGL Expression and Activity Impairs Cancer Pathogenicity

shMAGL cancer lines were next examined for alterations in pathogenicity using a set of in vitro and in vivo assays. shMAGL-melanoma (C8161), ovarian (SKOV3), and breast (231MFP) cancer cells exhibited significantly reduced in vitro migration (Figure 4A, F and Figure S2), invasion (Figure 4B, G and Figure S2), and cell survival under serum-starvation conditions (Figure 4C, H and Figure S2). Acute pharmacological blockade of MAGL by JZL184 also decreased cancer cell migration (Figure S2), but not survival, possibly indicating that maximal impairments in cancer aggressiveness require sustained inhibition of MAGL.

Figure 4 shRNA-mediated knockdown and pharmacological inhibition of MAGL impair cancer aggressiveness.

MAGL Overexpression Increases FFAs and the Aggressiveness of Cancer Cells

Stable MAGL-overexpressing (MAGL-OE) and control [expressing an empty vector or a catalytically inactive version of MAGL, where the serine nucleophile was mutated to alanine (S122A)] variants of MUM2C and OVCAR3 cells were generated by retroviral infection and evaluated for their respective MAGL activities by ABPP and C20:4 MAG substrate assays. Both assays confirmed that MAGL-OE cells possess greater than 10-fold elevations in MAGL activity compared to control cells (Figure 5A and Figure S4). MAGL-OE cells also showed significant reductions in MAGs (Figure 5B andFigure S4) and elevated FFAs (Figure 5C and Figure S4). This altered metabolic profile was accompanied by increased migration (Figure 5D and Figure S4), invasion (Figure 5E and Figure S4), and survival (Figure S4) in MAGL-OE cells. None of these effects were observed in cancer cells expressing the S122A MAGL mutant, indicating that they require MAGL activity. MAGL-OE MUM2C cells also showed enhanced tumor growth in vivo compared to control cells (Figure 5F). Notably, the increased tumor growth rate of MAGL-OE MUM2C cells nearly matched that of aggressive C8161 cells (Figure S4). These data indicate that the ectopic expression of MAGL in non-aggressive cancer cells is sufficient to elevate their FFA levels and promote pathogenicity both in vitro and in vivo.

Figure 5 Ectopic expression of MAGL elevates FFA levels and enhances the in vitro and in vivo pathogenicity of MUM2C melanoma cells.

Metabolic Rescue of Impaired Pathogenicity in MAGL-Disrupted Cancer Cells

MAGL could support the aggressiveness of cancer cells by either reducing the levels of its MAG substrates, elevating the levels of its FFA products, or both. Among MAGs, the principal signaling molecule is the endocannabinoid 2-AG, which activates the CB1 and CB2 receptors (Ahn et al., 2008; Mackie and Stella, 2006). The endocannabinoid system has been implicated previously in cancer progression and, depending on the specific study, shown to promote (Sarnataro et al., 2006; Zhao et al., 2005) or suppress (Endsley et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2008) cancer pathogenesis. Neither a CB1 or CB2 antagonist rescued the migratory defects of shMAGL cancer cells (Figure S5). CB1 and CB2 antagonists also did not affect the levels of MAGs or FFAs in cancer cells (Figure S5).

We then determined whether increased FFA delivery could rectify the tumor growth defect observed for shMAGL cells in vivo. Immune-deficient mice were fed either a normal chow or high-fat diet throughout the duration of a xenograft tumor growth experiment. Notably, the impaired tumor growth rate of shMAGL-C8161 cells was completely rescued in mice fed a high-fat diet. In contrast, shControl-C8161 cells showed equivalent tumor growth rates on a normal versus high-fat diet. The recovery in tumor growth for shMAGL-C8161 cells in the high-fat diet group correlated with significantly increases levels of FFAs in excised tumors (Figure 6D). Collectively, these results indicate that MAGL supports the pathogenic properties of cancer cells by maintaining tonically elevated levels of FFAs.

Figure 6 Recovery of the pathogenic properties of shMAGL cancer cells by treatment with exogenous fatty acids.

MAGL Regulates a Fatty Acid Network Enriched in Pro-Tumorigenic Signals

Studies revealed that neither

- the MAGL-FFA pathway might serve as a means to regenerate NAD+ (via continual fatty acyl glyceride/FFA recycling) to fuel glycolysis, or

- increased lipolysis could be to generate FFA substrates for β-oxidation, which may serve as an important energy source for cancer cells (Buzzai et al., 2005), or

- CPT1 blockade (reduced expression of CPT1 in aggressive cancer cells (data not shown) has been reported previously (Deberardinis et al., 2006))

providing evidence against a role for β-oxidation as a downstream mediator of the pathogenic effects of the MAGL-fatty acid pathway.

Considering that FFAs are fundamental building blocks for the production and remodeling of membrane structures and signaling molecules, perturbations in MAGL might be expected to affect several lipid-dependent biochemical networks important for malignancy. To test this hypothesis, we performed lipidomic analyses of cancer cell models with altered MAGL activity, including comparisons of:

- MAGL-OE versus control cancer cells (OVCAR3, MUM2C), and

- shMAGL versus shControl cancer cells (SKOV3, C8161).

Complementing these global profiles, we also conducted targeted measurements of specific bioactive lipids (e.g., prostaglandins) that are too low in abundance for detection by standard lipidomic methods. The resulting data sets were then mined to identify a common signature of lipid metabolites regulated by MAGL, which we defined as metabolites that were significantly increased or reduced in MAGL–OE cells and showed the opposite change in shMAGL cells relative to their respective control groups (Figure 7A, B and Table S4).

Figure 7 MAGL regulates a lipid network enriched in pro-tumorigenic signaling molecules.

Most of the lipids in the MAGL-fatty acid network, including several lysophospholipids (LPC, LPA, LPE), ether lipids (MAGE, alkyl LPE), phosphatidic acid (PA), and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), displayed similar profiles to FFAs, being consistently elevated and reduced in MAGL-OE and shMAGL cells, respectively. Only MAGs were found to show the opposite profile (elevated and reduced in shMAGL and MAGL-OE cells, respectively). Interestingly, virtually this entire lipidomic signature was also observed in aggressive cancer cells when compared to their non-aggressive counterparts (e.g., C8161 versus MUM2C and SKOV3 versus OVCAR3, respectively; Table S4). These findings demonstrate that MAGL regulates a lipid network in aggressive cancer cells that consists of not only FFAs and MAGs, but also a host of secondary lipid metabolites. Increases (rather than decreases) in LPCs and LPEs were observed in JZL184-treated cells (Figure S1 and Table S4). These data indicate that acute and chronic blockade of MAGL generate distinct metabolomic effects in cancer cells, likely reflecting the differential outcomes of short- versus long-term depletion of FFAs.