Metabolomics Summary and Perspective

Author and Curator: Larry H Bernstein, MD, FCAP

This is the final article in a robust series on metabolism, metabolomics, and the “-OMICS-“ biological synthesis that is creating a more holistic and interoperable view of natural sciences, including the biological disciplines, climate science, physics, chemistry, toxicology, pharmacology, and pathophysiology with as yet unforeseen consequences.

There have been impressive advances already in the research into developmental biology, plant sciences, microbiology, mycology, and human diseases, most notably, cancer, metabolic , and infectious, as well as neurodegenerative diseases.

Acknowledgements:

I write this article in honor of my first mentor, Harry Maisel, Professor and Emeritus Chairman of Anatomy, Wayne State University, Detroit, MI and to my stimulating mentors, students, fellows, and associates over many years:

Masahiro Chiga, MD, PhD, Averill A Liebow, MD, Nathan O Kaplan, PhD, Johannes Everse, PhD, Norio Shioura, PhD, Abraham Braude, MD, Percy J Russell, PhD, Debby Peters, Walter D Foster, PhD, Herschel Sidransky, MD, Sherman Bloom, MD, Matthew Grisham, PhD, Christos Tsokos, PhD, IJ Good, PhD, Distinguished Professor, Raool Banagale, MD, Gustavo Reynoso, MD,Gustave Davis, MD, Marguerite M Pinto, MD, Walter Pleban, MD, Marion Feietelson-Winkler, RD, PhD, John Adan,MD, Joseph Babb, MD, Stuart Zarich, MD, Inder Mayall, MD, A Qamar, MD, Yves Ingenbleek, MD, PhD, Emeritus Professor, Bette Seamonds, PhD, Larry Kaplan, PhD, Pauline Y Lau, PhD, Gil David, PhD, Ronald Coifman, PhD, Emeritus Professor, Linda Brugler, RD, MBA, James Rucinski, MD, Gitta Pancer, Ester Engelman, Farhana Hoque, Mohammed Alam, Michael Zions, William Fleischman, MD, Salman Haq, MD, Jerard Kneifati-Hayek, Madeleine Schleffer, John F Heitner, MD, Arun Devakonda,MD, Liziamma George,MD, Suhail Raoof, MD, Charles Oribabor,MD, Anthony Tortolani, MD, Prof and Chairman, JRDS Rosalino, PhD, Aviva Lev Ari, PhD, RN, Rosser Rudolph, MD, PhD, Eugene Rypka, PhD, Jay Magidson, PhD, Izaak Mayzlin, PhD, Maurice Bernstein, PhD, Richard Bing, Eli Kaplan, PhD, Maurice Bernstein, PhD.

This article has EIGHT parts, as follows:

Part 1

Metabolomics Continues Auspicious Climb

Part 2

Biologists Find ‘Missing Link’ in the Production of Protein Factories in Cells

Part 3

Neuroscience

Part 4

Cancer Research

Part 5

Metabolic Syndrome

Part 6

Biomarkers

Part 7

Epigenetics and Drug Metabolism

Part 8

Pictorial

genome cartoon

iron metabolism

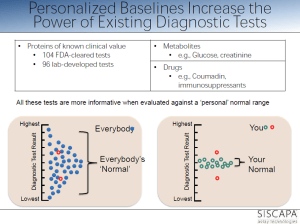

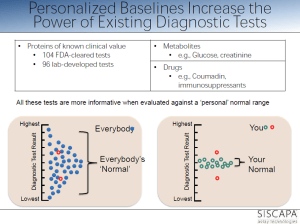

personalized reference range within population range

Part 1. MetabolomicsSurge

metagraph _OMICS

Metabolomics Continues Auspicious Climb

Jeffery Herman, Ph.D.

GEN May 1, 2012 (Vol. 32, No. 9)

Aberrant biochemical and metabolite signaling plays an important role in

- the development and progression of diseased tissue.

This concept has been studied by the science community for decades. However, with relatively

- recent advances in analytical technology and bioinformatics as well as

- the development of the Human Metabolome Database (HMDB),

metabolomics has become an invaluable field of research.

At the “International Conference and Exhibition on Metabolomics & Systems Biology” held recently in San Francisco, researchers and industry leaders discussed how

- the underlying cellular biochemical/metabolite fingerprint in response to

- a specific disease state,

- toxin exposure, or

- pharmaceutical compound

- is useful in clinical diagnosis and biomarker discovery and

- in understanding disease development and progression.

Developed by BASF, MetaMap® Tox is

- a database that helps identify in vivo systemic effects of a tested compound, including

- targeted organs,

- mechanism of action, and

- adverse events.

Based on 28-day systemic rat toxicity studies, MetaMap Tox is composed of

- differential plasma metabolite profiles of rats

- after exposure to a large variety of chemical toxins and pharmaceutical compounds.

“Using the reference data,

- we have developed more than 110 patterns of metabolite changes, which are

- specific and predictive for certain toxicological modes of action,”

said Hennicke Kamp, Ph.D., group leader, department of experimental toxicology and ecology at BASF.

With MetaMap Tox, a potential drug candidate

- can be compared to a similar reference compound

- using statistical correlation algorithms,

- which allow for the creation of a toxicity and mechanism of action profile.

“MetaMap Tox, in the context of early pre-clinical safety enablement in pharmaceutical development,” continued Dr. Kamp,

- has been independently validated “

- by an industry consortium (Drug Safety Executive Council) of 12 leading biopharmaceutical companies.”

Dr. Kamp added that this technology may prove invaluable

- allowing for quick and accurate decisions and

- for high-throughput drug candidate screening, in evaluation

- on the safety and efficacy of compounds

- during early and preclinical toxicological studies,

- by comparing a lead compound to a variety of molecular derivatives, and

- the rapid identification of the most optimal molecular structure

- with the best efficacy and safety profiles might be streamlined.

Dynamic Construct of the –Omics

Targeted Tandem Mass Spectrometry

Biocrates Life Sciences focuses on targeted metabolomics, an important approach for

- the accurate quantification of known metabolites within a biological sample.

Originally used for the clinical screening of inherent metabolic disorders from dried blood-spots of newborn children, Biocrates has developed

- a tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) platform, which allows for

- the identification,

- quantification, and

- mapping of more than 800 metabolites to specific cellular pathways.

It is based on flow injection analysis and high-performance liquid chromatography MS/MS.

common drug targets

The MetaDisIDQ® Kit is a

- “multiparamatic” diagnostic assay designed for the “comprehensive assessment of a person’s metabolic state” and

- the early determination of pathophysiological events with regards to a specific disease.

MetaDisIDQ is designed to quantify

- a diverse range of 181 metabolites involved in major metabolic pathways

- from a small amount of human serum (10 µL) using isotopically labeled internal standards,

This kit has been demonstrated to detect changes in metabolites that are commonly associated with the development of

- metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and diabetic nephropathy,

Dr. Dallman reports that data generated with the MetaDisIDQ kit correlates strongly with

- routine chemical analyses of common metabolites including glucose and creatinine

Biocrates has also developed the MS/MS-based AbsoluteIDQ® kits, which are

- an “easy-to-use” biomarker analysis tool for laboratory research.

The kit functions on MS machines from a variety of vendors, and allows for the quantification of 150-180 metabolites.

The SteroIDQ® kit is a high-throughput standardized MS/MS diagnostic assay,

- validated in human serum, for the rapid and accurate clinical determination of 16 known steroids.

Initially focusing on the analysis of steroid ranges for use in hormone replacement therapy, the SteroIDQ Kit is expected to have a wide clinical application.

Hormone-Resistant Breast Cancer

Scientists at Georgetown University have shown that

- breast cancer cells can functionally coordinate cell-survival and cell-proliferation mechanisms,

- while maintaining a certain degree of cellular metabolism.

To grow, cells need energy, and energy is a product of cellular metabolism. For nearly a century, it was thought that

- the uncoupling of glycolysis from the mitochondria,

- leading to the inefficient but rapid metabolism of glucose and

- the formation of lactic acid (the Warburg effect), was

the major and only metabolism driving force for unchecked proliferation and tumorigenesis of cancer cells.

Other aspects of metabolism were often overlooked.

“.. we understand now that

- cellular metabolism is a lot more than just metabolizing glucose,”

said Robert Clarke, Ph.D., professor of oncology and physiology and biophysics at Georgetown University. Dr. Clarke, in collaboration with the Waters Center for Innovation at Georgetown University (led by Albert J. Fornace, Jr., M.D.), obtained

- the metabolomic profile of hormone-sensitive and -resistant breast cancer cells through the use of UPLC-MS.

They demonstrated that breast cancer cells, through a rather complex and not yet completely understood process,

- can functionally coordinate cell-survival and cell-proliferation mechanisms,

- while maintaining a certain degree of cellular metabolism.

This is at least partly accomplished through the upregulation of important pro-survival mechanisms; including

- the unfolded protein response;

- a regulator of endoplasmic reticulum stress and

- initiator of autophagy.

Normally, during a stressful situation, a cell may

- enter a state of quiescence and undergo autophagy,

- a process by which a cell can recycle organelles

- in order to maintain enough energy to survive during a stressful situation or,

if the stress is too great,

By integrating cell-survival mechanisms and cellular metabolism

- advanced ER+ hormone-resistant breast cancer cells

- can maintain a low level of autophagy

- to adapt and resist hormone/chemotherapy treatment.

This adaptation allows cells

- to reallocate important metabolites recovered from organelle degradation and

- provide enough energy to also promote proliferation.

With further research, we can gain a better understanding of the underlying causes of hormone-resistant breast cancer, with

- the overall goal of developing effective diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic tools.

NMR

Over the last two decades, NMR has established itself as a major tool for metabolomics analysis. It is especially adept at testing biological fluids. [Bruker BioSpin]

Historically, nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR) has been used for structural elucidation of pure molecular compounds. However, in the last two decades, NMR has established itself as a major tool for metabolomics analysis. Since

- the integral of an NMR signal is directly proportional to

- the molar concentration throughout the dynamic range of a sample,

“the simultaneous quantification of compounds is possible

- without the need for specific reference standards or calibration curves,” according to Lea Heintz of Bruker BioSpin.

NMR is adept at testing biological fluids because of

- high reproducibility,

- standardized protocols,

- low sample manipulation, and

- the production of a large subset of data,

Bruker BioSpin is presently involved in a project for the screening of inborn errors of metabolism in newborn children from Turkey, based on their urine NMR profiles. More than 20 clinics are participating to the project that is coordinated by INFAI, a specialist in the transfer of advanced analytical technology into medical diagnostics. The construction of statistical models are being developed

- for the detection of deviations from normality, as well as

- automatic quantification methods for indicative metabolites

Bruker BioSpin recently installed high-resolution magic angle spinning NMR (HRMAS-NMR) systems that can rapidly analyze tissue biopsies. The main objective for HRMAS-NMR is to establish a rapid and effective clinical method to assess tumor grade and other important aspects of cancer during surgery.

Combined NMR and Mass Spec

There is increasing interest in combining NMR and MS, two of the main analytical assays in metabolomic research, as a means

- to improve data sensitivity and to

- fully elucidate the complex metabolome within a given biological sample.

- to realize a potential for cancer biomarker discovery in the realms of diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment.

.

Using combined NMR and MS to measure the levels of nearly 250 separate metabolites in the patient’s blood, Dr. Weljie and other researchers at the University of Calgary were able to rapidly determine the malignancy of a pancreatic lesion (in 10–15% of the cases, it is difficult to discern between benign and malignant), while avoiding unnecessary surgery in patients with benign lesions.

When performing NMR and MS on a single biological fluid, ultimately “we are,” noted Dr. Weljie,

- “splitting up information content, processing, and introducing a lot of background noise and error and

- then trying to reintegrate the data…

It’s like taking a complex item, with multiple pieces, out of an IKEA box and trying to repackage it perfectly into another box.”

By improving the workflow between the initial splitting of the sample, they improved endpoint data integration, proving that

- a streamlined approach to combined NMR/MS can be achieved,

- leading to a very strong, robust and precise metabolomics toolset.

Metabolomics Research Picks Up Speed

Field Advances in Quest to Improve Disease Diagnosis and Predict Drug Response

John Morrow Jr., Ph.D.

GEN May 1, 2011 (Vol. 31, No. 9)

As an important discipline within systems biology, metabolomics is being explored by a number of laboratories for

- its potential in pharmaceutical development.

Studying metabolites can offer insights into the relationships between genotype and phenotype, as well as between genotype and environment. In addition, there is plenty to work with—there are estimated to be some 2,900 detectable metabolites in the human body, of which

- 309 have been identified in cerebrospinal fluid,

- 1,122 in serum,

- 458 in urine, and

- roughly 300 in other compartments.

Guowang Xu, Ph.D., a researcher at the Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics. is investigating the causes of death in China,

- and how they have been changing over the years as the country has become a more industrialized nation.

- the increase in the incidence of metabolic disorders such as diabetes has grown to affect 9.7% of the Chinese population.

Dr. Xu, collaborating with Rainer Lehman, Ph.D., of the University of Tübingen, Germany, compared urinary metabolites in samples from healthy individuals with samples taken from prediabetic, insulin-resistant subjects. Using mass spectrometry coupled with electrospray ionization in the positive mode, they observed striking dissimilarities in levels of various metabolites in the two groups.

“When we performed a comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography, time-of-flight mass spectrometry analysis of our samples, we observed several metabolites, including

- 2-hydroxybutyric acid in plasma,

- as potential diabetes biomarkers,” Dr. Xu explains.

In other, unrelated studies, Dr. Xu and the German researchers used a metabolomics approach to investigate the changes in plasma metabolite profiles immediately after exercise and following a 3-hour and 24-hour period of recovery. They found that

- medium-chain acylcarnitines were the most distinctive exercise biomarkers, and

- they are released as intermediates of partial beta oxidation in human myotubes and mouse muscle tissue.

Dr. Xu says. “The traditional approach of assessment based on a singular biomarker is being superseded by the introduction of multiple marker profiles.”

Typical of the studies under way by Dr. Kaddurah-Daouk and her colleaguesat Duke University

- is a recently published investigation highlighting the role of an SNP variant in

- the glycine dehydrogenase gene on individual response to antidepressants.

- patients who do not respond to the selective serotonin uptake inhibitors citalopram and escitalopram

- carried a particular single nucleotide polymorphism in the GD gene.

“These results allow us to pinpoint a possible

- role for glycine in selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor response and

- illustrate the use of pharmacometabolomics to inform pharmacogenomics.

These discoveries give us the tools for prognostics and diagnostics so that

- we can predict what conditions will respond to treatment.

“This approach to defining health or disease in terms of metabolic states opens a whole new paradigm.

By screening hundreds of thousands of molecules, we can understand

- the relationship between human genetic variability and the metabolome.”

Dr. Kaddurah-Daouk talks about statins as a current

- model of metabolomics investigations.

It is now known that the statins have widespread effects, altering a range of metabolites. To sort out these changes and develop recommendations for which individuals should be receiving statins will require substantial investments of energy and resources into defining the complex web of biochemical changes that these drugs initiate.

Furthermore, Dr. Kaddurah-Daouk asserts that,

- “genetics only encodes part of the phenotypic response.

One needs to take into account the

- net environment contribution in order to determine

- how both factors guide the changes in our metabolic state that determine the phenotype.”

Interactive Metabolomics

Researchers at the University of Nottingham use diffusion-edited nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy to assess the effects of a biological matrix on metabolites. Diffusion-edited NMR experiments provide a way to

- separate the different compounds in a mixture

- based on the differing translational diffusion coefficients (which reflect the size and shape of the molecule).

The measurements are carried out by observing

- the attenuation of the NMR signals during a pulsed field gradient experiment.

Clare Daykin, Ph.D., is a lecturer at the University of Nottingham, U.K. Her field of investigation encompasses “interactive metabolomics,”which she defines as

“the study of the interactions between low molecular weight biochemicals and macromolecules in biological samples ..

- without preselection of the components of interest.

“Blood plasma is a heterogeneous mixture of molecules that

- undergo a variety of interactions including metal complexation,

- chemical exchange processes,

- micellar compartmentation,

- enzyme-mediated biotransformations, and

- small molecule–macromolecular binding.”

Many low molecular weight compounds can exist

- freely in solution,

- bound to proteins, or

- within organized aggregates such as lipoprotein complexes.

Therefore, quantitative comparison of plasma composition from

- diseased individuals compared to matched controls provides an incomplete insight to plasma metabolism.

“It is not simply the concentrations of metabolites that must be investigated,

- but their interactions with the proteins and lipoproteins within this complex web.

Rather than targeting specific metabolites of interest, Dr. Daykin’s metabolite–protein binding studies aim to study

- the interactions of all detectable metabolites within the macromolecular sample.

Such activities can be studied through the use of diffusion-edited nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, in which one can assess

- the effects of the biological matrix on the metabolites.

“This can lead to a more relevant and exact interpretation

- for systems where metabolite–macromolecule interactions occur.”

Diffusion-edited NMR experiments provide a way to separate the different compounds in a mixture based on

- the differing translational diffusion coefficients (which reflect the size and shape of the molecule).

The measurements are carried out by observing

- the attenuation of the NMR signals during a pulsed field gradient experiment.

Pushing the Limits

It is widely recognized that many drug candidates fail during development due to ancillary toxicity. Uwe Sauer, Ph.D., professor, and Nicola Zamboni, Ph.D., researcher, both at the Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule, Zürich (ETH Zürich), are applying

- high-throughput intracellular metabolomics to understand

- the basis of these unfortunate events and

- head them off early in the course of drug discovery.

“Since metabolism is at the core of drug toxicity, we developed a platform for

- measurement of 50–100 targeted metabolites by

- a high-throughput system consisting of flow injection

- coupled to tandem mass spectrometry.”

Using this approach, Dr. Sauer’s team focused on

- the central metabolism of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, reasoning that

- this core network would be most susceptible to potential drug toxicity.

Screening approximately 41 drugs that were administered at seven concentrations over three orders of magnitude, they observed changes in metabolome patterns at much lower drug concentrations without attendant physiological toxicity.

The group carried out statistical modeling of about

- 60 metabolite profiles for each drug they evaluated.

This data allowed the construction of a “profile effect map” in which

- the influence of each drug on metabolite levels can be followed, including off-target effects, which

- provide an indirect measure of the possible side effects of the various drugs.

Dr. Sauer says.“We have found that this approach is

- at least 100 times as fast as other omics screening platforms,”

“Some drugs, including many anticancer agents,

- disrupt metabolism long before affecting growth.”

killing cancer cells

Furthermore, they used the principle of 13C-based flux analysis, in which

- metabolites labeled with 13C are used to follow the utilization of metabolic pathways in the cell.

These 13C-determined intracellular responses of metabolic fluxes to drug treatment demonstrate

- the functional performance of the network to be rather robust,

conformational changes leading to substrate efflux.

leading Dr. Sauer to the conclusion that

- the phenotypic vigor he observes to drug challenges

- is achieved by a flexible make up of the metabolome.

Dr. Sauer is confident that it will be possible to expand the scope of these investigations to hundreds of thousands of samples per study. This will allow answers to the questions of

- how cells establish a stable functioning network in the face of inevitable concentration fluctuations.

Is Now the Hour?

There is great enthusiasm and agitation within the biotech community for

- metabolomics approaches as a means of reversing the dismal record of drug discovery

that has accumulated in the last decade.

While the concept clearly makes sense and is being widely applied today, there are many reasons why drugs fail in development, and metabolomics will not be a panacea for resolving all of these questions. It is too early at this point to recognize a trend or a track record, and it will take some time to see how this approach can aid in drug discovery and shorten the timeline for the introduction of new pharmaceutical agents.

Degree of binding correlated with function

Diagram_of_a_two-photon_excitation_microscope_

Part 2. Biologists Find ‘Missing Link’ in the Production of Protein Factories in Cells

Biologists at UC San Diego have found

- the “missing link” in the chemical system that

- enables animal cells to produce ribosomes

—the thousands of protein “factories” contained within each cell that

- manufacture all of the proteins needed to build tissue and sustain life.

‘Missing Link’

Their discovery, detailed in the June 23 issue of the journal Genes & Development, will not only force

- a revision of basic textbooks on molecular biology, but also

- provide scientists with a better understanding of

- how to limit uncontrolled cell growth, such as cancer,

- that might be regulated by controlling the output of ribosomes.

Ribosomes are responsible for the production of the wide variety of proteins that include

- enzymes;

- structural molecules, such as hair,

- skin and bones;

- hormones like insulin; and

- components of our immune system such as antibodies.

Regarded as life’s most important molecular machine, ribosomes have been intensively studied by scientists (the 2009 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, for example, was awarded for studies of its structure and function). But until now researchers had not uncovered all of the details of how the proteins that are used to construct ribosomes are themselves produced.

In multicellular animals such as humans,

- ribosomes are made up of about 80 different proteins

(humans have 79 while some other animals have a slightly different number) as well as

- four different kinds of RNA molecules.

In 1969, scientists discovered that

- the synthesis of the ribosomal RNAs is carried out by specialized systems using two key enzymes:

- RNA polymerase I and RNA polymerase III.

But until now, scientists were unsure if a complementary system was also responsible for

- the production of the 80 proteins that make up the ribosome.

That’s essentially what the UC San Diego researchers headed by Jim Kadonaga, a professor of biology, set out to examine. What they found was the missing link—the specialized

- system that allows ribosomal proteins themselves to be synthesized by the cell.

Kadonaga says that he and coworkers found that ribosomal proteins are synthesized via

- a novel regulatory system with the enzyme RNA polymerase II and

- a factor termed TRF2,”

“For the production of most proteins,

- RNA polymerase II functions with

- a factor termed TBP,

- but for the synthesis of ribosomal proteins, it uses TRF2.”

- this specialized TRF2-based system for ribosome biogenesis

- provides a new avenue for the study of ribosomes and

- its control of cell growth, and

“it should lead to a better understanding and potential treatment of diseases such as cancer.”

Coordination of the transcriptome and metabolome

the potential advantages conferred by distal-site protein synthesis

Other authors of the paper were UC San Diego biologists Yuan-Liang Wang, Sascha Duttke and George Kassavetis, and Kai Chen, Jeff Johnston, and Julia Zeitlinger of the Stowers Institute for Medical Research in Kansas City, Missouri. Their research was supported by two grants from the National Institutes of Health (1DP2OD004561-01 and R01 GM041249).

Turning Off a Powerful Cancer Protein

Scientists have discovered how to shut down a master regulatory transcription factor that is

- key to the survival of a majority of aggressive lymphomas,

- which arise from the B cells of the immune system.

The protein, Bcl6, has long been considered too complex to target with a drug since it is also crucial

- to the healthy functioning of many immune cells in the body, not just B cells gone bad.

The researchers at Weill Cornell Medical College report that it is possible

- to shut down Bcl6 in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL)

- while not affecting its vital function in T cells and macrophages

- that are needed to support a healthy immune system.

If Bcl6 is completely inhibited, patients might suffer from systemic inflammation and atherosclerosis. The team conducted this new study to help clarify possible risks, as well as to understand

- how Bcl6 controls the various aspects of the immune system.

The findings in this study were inspired from

- preclinical testing of two Bcl6-targeting agents that Dr. Melnick and his Weill Cornell colleagues have developed

- to treat DLBCLs.

These experimental drugs are

- RI-BPI, a peptide mimic, and

- the small molecule agent 79-6.

“This means the drugs we have developed against Bcl6 are more likely to be

- significantly less toxic and safer for patients with this cancer than we realized,”

says Ari Melnick, M.D., professor of hematology/oncology and a hematologist-oncologist at NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center.

Dr. Melnick says the discovery that

- a master regulatory transcription factor can be targeted

- offers implications beyond just treating DLBCL.

Recent studies from Dr. Melnick and others have revealed that

- Bcl6 plays a key role in the most aggressive forms of acute leukemia, as well as certain solid tumors.

Bcl6 can control the type of immune cell that develops in the bone marrow—playing many roles

- in the development of B cells, T cells, macrophages, and other cells—including a primary and essential role in

- enabling B-cells to generate specific antibodies against pathogens.

According to Dr. Melnick, “When cells lose control of Bcl6,

- lymphomas develop in the immune system.

Lymphomas are ‘addicted’ to Bcl6, and therefore

- Bcl6 inhibitors powerfully and quickly destroy lymphoma cells,” .

The big surprise in the current study is that rather than functioning as a single molecular machine,

- Bcl6 functions like a Swiss Army knife,

- using different tools to control different cell types.

This multifunction paradigm could represent a general model for the functioning of other master regulatory transcription factors.

“In this analogy, the Swiss Army knife, or transcription factor, keeps most of its tools folded,

- opening only the one it needs in any given cell type,”

He makes the following analogy:

- “For B cells, it might open and use the knife tool;

- for T cells, the cork screw;

- for macrophages, the scissors.”

“this means that you only need to prevent the master regulator from using certain tools to treat cancer. You don’t need to eliminate the whole knife,” . “In fact, we show that taking out the whole knife is harmful since

- the transcription factor has many other vital functions that other cells in the body need.”

Prior to these study results, it was not known that a master regulator could separate its functions so precisely. Researchers hope this will be a major benefit to the treatment of DLBCL and perhaps other disorders that are influenced by Bcl6 and other master regulatory transcription factors.

The study is published in the journal Nature Immunology, in a paper titled “Lineage-specific functions of Bcl-6 in immunity and inflammation are mediated by distinct biochemical mechanisms”.

Part 3. Neuroscience

Vesicles influence function of nerve cells

Oct, 06 2014 source: http://feeds.sciencedaily.com

Neurons (blue) which have absorbed exosomes (green) have increased levels of the enzyme catalase (red), which helps protect them against peroxides.

Neurons (blue) which have absorbed exosomes (green) have increased levels of the enzyme catalase (red), which helps protect them against peroxides.

Tiny vesicles containing protective substances

- which they transmit to nerve cells apparently

- play an important role in the functioning of neurons.

As cell biologists at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (JGU) have discovered,

- nerve cells can enlist the aid of mini-vesicles of neighboring glial cells

- to defend themselves against stress and other potentially detrimental factors.

These vesicles, called exosomes, appear to stimulate the neurons on various levels:

- they influence electrical stimulus conduction,

- biochemical signal transfer, and

- gene regulation.

Exosomes are thus multifunctional signal emitters

- that can have a significant effect in the brain.

Exosome

The researchers in Mainz already observed in a previous study that

- oligodendrocytes release exosomes on exposure to neuronal stimuli.

- these are absorbed by the neurons and improve neuronal stress tolerance.

Oligodendrocytes, a type of glial cell, form an

- insulating myelin sheath around the axons of neurons.

The exosomes transport protective proteins such as

- heat shock proteins,

- glycolytic enzymes, and

- enzymes that reduce oxidative stress from one cell type to another,

- but also transmit genetic information in the form of ribonucleic acids.

“As we have now discovered in cell cultures, exosomes seem to have a whole range of functions,” explained Dr. Eva-Maria Krmer-Albers. By means of their transmission activity, the small bubbles that are the vesicles

- not only promote electrical activity in the nerve cells, but also

- influence them on the biochemical and gene regulatory level.

“The extent of activities of the exosomes is impressive,” added Krmer-Albers. The researchers hope that the understanding of these processes will contribute to the development of new strategies for the treatment of neuronal diseases. Their next aim is to uncover how vesicles actually function in the brains of living organisms.

http://labroots.com/user/news/article/id/217438/title/vesicles-influence-function-of-nerve-cells

The above story is based on materials provided by Universitt Mainz.

Universitt Mainz. “Vesicles influence function of nerve cells.” ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 6 October 2014. www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2014/10/141006174214.htm

Neuroscientists use snail research to help explain “chemo brain”

10/08/2014

It is estimated that as many as half of patients taking cancer drugs experience a decrease in mental sharpness. While there have been many theories, what causes “chemo brain” has eluded scientists.

In an effort to solve this mystery, neuroscientists at The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth) conducted an experiment in an animal memory model and their results point to a possible explanation. Findings appeared in The Journal of Neuroscience.

In the study involving a sea snail that shares many of the same memory mechanisms as humans and a drug used to treat a variety of cancers, the scientists identified

- memory mechanisms blocked by the drug.

Then, they were able to counteract or

- unblock the mechanisms by administering another agent.

“Our research has implications in the care of people given to cognitive deficits following drug treatment for cancer,” said John H. “Jack” Byrne, Ph.D., senior author, holder of the June and Virgil Waggoner Chair and Chairman of the Department of Neurobiology and Anatomy at the UTHealth Medical School. “There is no satisfactory treatment at this time.”

Byrne’s laboratory is known for its use of a large snail called Aplysia californica to further the understanding of the biochemical signaling among nerve cells (neurons). The snails have large neurons that relay information much like those in humans.

When Byrne’s team compared cell cultures taken from normal snails to

- those administered a dose of a cancer drug called doxorubicin,

the investigators pinpointed a neuronal pathway

- that was no longer passing along information properly.

With the aid of an experimental drug,

- the scientists were able to reopen the pathway.

Unfortunately, this drug would not be appropriate for humans, Byrne said. “We want to identify other drugs that can rescue these memory mechanisms,” he added.

According the American Cancer Society, some of the distressing mental changes cancer patients experience may last a short time or go on for years.

Byrne’s UT Health research team includes co-lead authors Rong-Yu Liu, Ph.D., and Yili Zhang, Ph.D., as well as Brittany Coughlin and Leonard J. Cleary, Ph.D. All are affiliated with the W.M. Keck Center for the Neurobiology of Learning and Memory.

Byrne and Cleary also are on the faculty of The University of Texas Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences at Houston. Coughlin is a student at the school, which is jointly operated by UT Health and The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center.

The study titled “Doxorubicin Attenuates Serotonin-Induced Long-Term Synaptic Facilitation by Phosphorylation of p38 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase” received support from National Institutes of Health grant (NS019895) and the Zilkha Family Discovery Fellowship.

Doxorubicin Attenuates Serotonin-Induced Long-Term Synaptic Facilitation by Phosphorylation of p38 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase

Source: Univ. of Texas Health Science Center at Houston

http://www.rdmag.com/news/2014/10/neuroscientists-use-snail-research-help-explain-E2_9_Cchemo-brain

Doxorubicin Attenuates Serotonin-Induced Long-Term Synaptic Facilitation by Phosphorylation of p38 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase

Rong-Yu Liu*, Yili Zhang*, Brittany L. Coughlin, Leonard J. Cleary, and John H. Byrne +Show Affiliations

The Journal of Neuroscience, 1 Oct 2014, 34(40): 13289-13300;

http://dx.doi.org:/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0538-14.2014

Doxorubicin (DOX) is an anthracycline used widely for cancer chemotherapy. Its primary mode of action appears to be

- topoisomerase II inhibition, DNA cleavage, and free radical generation.

However, in non-neuronal cells, DOX also inhibits the expression of

- dual-specificity phosphatases (also referred to as MAPK phosphatases) and thereby

- inhibits the dephosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and

- p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38 MAPK),

- two MAPK isoforms important for long-term memory (LTM) formation.

Activation of these kinases by DOX in neurons, if present,

- could have secondary effects on cognitive functions, such as learning and memory.

The present study used cultures of rat cortical neurons and sensory neurons (SNs) of Aplysia

- to examine the effects of DOX on levels of phosphorylated ERK (pERK) and

- phosphorylated p38 (p-p38) MAPK.

In addition, Aplysia neurons were used to examine the effects of DOX on

- long-term enhanced excitability, long-term synaptic facilitation (LTF), and

- long-term synaptic depression (LTD).

DOX treatment led to elevated levels of

- pERK and p-p38 MAPK in SNs and cortical neurons.

In addition, it increased phosphorylation of

- the downstream transcriptional repressor cAMP response element-binding protein 2 in SNs.

DOX treatment blocked serotonin-induced LTF and enhanced LTD induced by the neuropeptide Phe-Met-Arg-Phe-NH2. The block of LTF appeared to be attributable to

- overriding inhibitory effects of p-p38 MAPK, because

- LTF was rescued in the presence of an inhibitor of p38 MAPK

(SB203580 [4-(4-fluorophenyl)-2-(4-methylsulfinylphenyl)-5-(4-pyridyl)-1H-imidazole]) .

These results suggest that acute application of DOX might impair the formation of LTM via the p38 MAPK pathway.

Terms: Aplysia chemotherapy ERK p38 MAPK serotonin synaptic plasticity

Technology that controls brain cells with radio waves earns early BRAIN grant

10/08/2014

bright spots = cells with increased calcium after treatment with radio waves, allows neurons to fire

BRAIN control: The new technology uses radio waves to activate or silence cells remotely. The bright spots above represent cells with increased calcium after treatment with radio waves, a change that would allow neurons to fire.

A proposal to develop a new way to

- remotely control brain cells

from Sarah Stanley, a research associate in Rockefeller University’s Laboratory of Molecular Genetics, headed by Jeffrey M. Friedman, is

- among the first to receive funding from U.S. President Barack Obama’s BRAIN initiative.

The project will make use of a technique called

- radiogenetics that combines the use of radio waves or magnetic fields with

- nanoparticles to turn neurons on or off.

The National Institutes of Health is one of four federal agencies involved in the BRAIN (Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies) initiative. Following in the ambitious footsteps of the Human Genome Project, the BRAIN initiative seeks

- to create a dynamic map of the brain in action,

a goal that requires the development of new technologies. The BRAIN initiative working group, which outlined the broad scope of the ambitious project, was co-chaired by Rockefeller’s Cori Bargmann, head of the Laboratory of Neural Circuits and Behavior.

Stanley’s grant, for $1.26 million over three years, is one of 58 projects to get BRAIN grants, the NIH announced. The NIH’s plan for its part of this national project, which has been pitched as “America’s next moonshot,” calls for $4.5 billion in federal funds over 12 years.

The technology Stanley is developing would

- enable researchers to manipulate the activity of neurons, as well as other cell types,

- in freely moving animals in order to better understand what these cells do.

Other techniques for controlling selected groups of neurons exist, but her new nanoparticle-based technique has a

- unique combination of features that may enable new types of experimentation.

- it would allow researchers to rapidly activate or silence neurons within a small area of the brain or

- dispersed across a larger region, including those in difficult-to-access locations.

Stanley also plans to explore the potential this method has for use treating patients.

“Francis Collins, director of the NIH, has discussed

- the need for studying the circuitry of the brain,

- which is formed by interconnected neurons.

Our remote-control technology may provide a tool with which researchers can ask new questions about the roles of complex circuits in regulating behavior,” Stanley says.

Rockefeller University’s Laboratory of Molecular Genetics

Source: Rockefeller Univ.

Part 4. Cancer

Two Proteins Found to Block Cancer Metastasis

Why do some cancers spread while others don’t? Scientists have now demonstrated that

- metastatic incompetent cancers actually “poison the soil”

- by generating a micro-environment that blocks cancer cells

- from settling and growing in distant organs.

The “seed and the soil” hypothesis proposed by Stephen Paget in 1889 is now widely accepted to explain how

- cancer cells (seeds) are able to generate fertile soil (the micro-environment)

- in distant organs that promotes cancer’s spread.

However, this concept had not explained why some tumors do not spread or metastasize.

The researchers, from Weill Cornell Medical College, found that

- two key proteins involved in this process work by

- dramatically suppressing cancer’s spread.

The study offers hope that a drug based on these

- potentially therapeutic proteins, prosaposin and Thrombospondin 1 (Tsp-1),

might help keep human cancer at bay and from metastasizing.

Scientists don’t understand why some tumors wouldn’t “want” to spread. It goes against their “job description,” says the study’s senior investigator, Vivek Mittal, Ph.D., an associate professor of cell and developmental biology in cardiothoracic surgery and director of the Neuberger Berman Foundation Lung Cancer Laboratory at Weill Cornell Medical College. He theorizes that metastasis occurs when

- the barriers that the body throws up to protect itself against cancer fail.

But there are some tumors in which some of the barriers may still be intact. “So that suggests

- those primary tumors will continue to grow, but that

- an innate protective barrier still exists that prevents them from spreading and invading other organs,”

The researchers found that, like typical tumors,

- metastasis-incompetent tumors also send out signaling molecules

- that establish what is known as the “premetastatic niche” in distant organs.

These niches composed of bone marrow cells and various growth factors have been described previously by others including Dr. Mittal as the fertile “soil” that the disseminated cancer cell “seeds” grow in.

Weill Cornell’s Raúl Catena, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow in Dr. Mittal’s laboratory, found an important difference between the tumor types. Metastatic-incompetent tumors

- systemically increased expression of Tsp-1, a molecule known to fight cancer growth.

- increased Tsp-1 production was found specifically in the bone marrow myeloid cells

- that comprise the metastatic niche.

These results were striking, because for the first time Dr. Mittal says

- the bone marrow-derived myeloid cells were implicated as

- the main producers of Tsp-1,.

In addition, Weill Cornell and Harvard researchers found that

- prosaposin secreted predominantly by the metastatic-incompetent tumors

- increased expression of Tsp-1 in the premetastatic lungs.

Thus, Dr. Mittal posits that prosaposin works in combination with Tsp-1

- to convert pro-metastatic bone marrow myeloid cells in the niche

- into cells that are not hospitable to cancer cells that spread from a primary tumor.

- “The very same myeloid cells in the niche that we know can promote metastasis

- can also be induced under the command of the metastatic incompetent primary tumor to inhibit metastasis,”

The research team found that

- the Tsp-1–inducing activity of prosaposin

- was contained in only a 5-amino acid peptide region of the protein, and

- this peptide alone induced Tsp-1 in the bone marrow cells and

- effectively suppressed metastatic spread in the lungs

- in mouse models of breast and prostate cancer.

This 5-amino acid peptide with Tsp-1–inducing activity

- has the potential to be used as a therapeutic agent against metastatic cancer,

The scientists have begun to test prosaposin in other tumor types or metastatic sites.

Dr. Mittal says that “The clinical implications of the study are:

- “Not only is it theoretically possible to design a prosaposin-based drug or drugs

- that induce Tsp-1 to block cancer spread, but

- you could potentially create noninvasive prognostic tests

- to predict whether a cancer will metastasize.”

The study was reported in the April 30 issue of Cancer Discovery, in a paper titled “Bone Marrow-Derived Gr1+ Cells Can Generate a Metastasis-Resistant Microenvironment Via Induced Secretion of Thrombospondin-1”.

Disabling Enzyme Cripples Tumors, Cancer Cells

First Step of Metastasis

Published: Sep 05, 2013 http://www.technologynetworks.com/Metabolomics/news.aspx?id=157138

Knocking out a single enzyme dramatically cripples the ability of aggressive cancer cells to spread and grow tumors.

The paper, published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, sheds new light on the importance of lipids, a group of molecules that includes fatty acids and cholesterol, in the development of cancer.

Researchers have long known that cancer cells metabolize lipids differently than normal cells. Levels of ether lipids – a class of lipids that are harder to break down – are particularly elevated in highly malignant tumors.

“Cancer cells make and use a lot of fat and lipids, and that makes sense because cancer cells divide and proliferate at an accelerated rate, and to do that,

- they need lipids, which make up the membranes of the cell,”

said study principal investigator Daniel Nomura, assistant professor in UC Berkeley’s Department of Nutritional Sciences and Toxicology. “Lipids have a variety of uses for cellular structure, but what we’re showing with our study is that

- lipids can send signals that fuel cancer growth.”

In the study, Nomura and his team tested the effects of reducing ether lipids on human skin cancer cells and primary breast tumors. They targeted an enzyme,

- alkylglycerone phosphate synthase, or AGPS,

- known to be critical to the formation of ether lipids.

The researchers confirmed that

- AGPS expression increased when normal cells turned cancerous.

- inactivating AGPS substantially reduced the aggressiveness of the cancer cells.

“The cancer cells were less able to move and invade,” said Nomura.

The researchers also compared the impact of

- disabling the AGPS enzyme in mice that had been injected with cancer cells.

Nomura. observes -“Among the mice that had the AGPS enzyme inactivated,

- the tumors were nonexistent,”

“The mice that did not have this enzyme

- disabled rapidly developed tumors.”

The researchers determined that

- inhibiting AGPS expression depleted the cancer cells of ether lipids.

- AGPS altered levels of other types of lipids important to the ability of the cancer cells to survive and spread, including

- prostaglandins and acyl phospholipids.

“What makes AGPS stand out as a treatment target is that the enzyme seems to simultaneously

- regulate multiple aspects of lipid metabolism

- important for tumor growth and malignancy.”

Future steps include the

- development of AGPS inhibitors for use in cancer therapy,

“This study sheds considerable light on the important role that AGPS plays in ether lipid metabolism in cancer cells, and it suggests that

- inhibitors of this enzyme could impair tumor formation,”

said Benjamin Cravatt, Professor and Chair of Chemical Physiology at The Scripps Research Institute, who is not part of the UC.

Agilent Technologies Thought Leader Award Supports Translational Research Program

Published: Mon, March 04, 2013

The award will support Dr DePinho’s research into

- metabolic reprogramming in the earliest stages of cancer.

Agilent Technologies Inc. announces that Dr. Ronald A. DePinho, a world-renowned oncologist and researcher, has received an Agilent Thought Leader Award.

DePinho is president of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. DePinho and his team hope to discover and characterize

- alterations in metabolic flux during tumor initiation and maintenance, and to identify biomarkers for early detection of pancreatic cancer together with

- novel therapeutic targets.

Researchers on his team will work with scientists from the university’s newly formed Institute of Applied Cancer Sciences.

The Agilent Thought Leader Award provides funds to support personnel as well as a state-of-the-art Agilent 6550 iFunnel Q-TOF LC/MS system.

“I am extremely pleased to receive this award for metabolomics research, as the survival rates for pancreatic cancer have not significantly improved over the past 20 years,” DePinho said. “This technology will allow us to

- rapidly identify new targets that drive the formation, progression and maintenance of pancreatic cancer.

Discoveries from this research will also lead to

- the development of effective early detection biomarkers and novel therapeutic interventions.”

“We are proud to support Dr. DePinho’s exciting translational research program, which will make use of

- metabolomics and integrated biology workflows and solutions in biomarker discovery,”

said Patrick Kaltenbach, Agilent vice president, general manager of the Liquid Phase Division, and the executive sponsor of this award.

The Agilent Thought Leader Program promotes fundamental scientific advances by support of influential thought leaders in the life sciences and chemical analysis fields.

The covalent modifier Nedd8 is critical for the activation of Smurf1 ubiquitin ligase in tumorigenesis

Ping Xie, Minghua Zhang, Shan He, Kefeng Lu, Yuhan Chen, Guichun Xing, et al.

Nature Communications 2014; 5(3733). http://dx.doi.org:/10.1038/ncomms4733

Neddylation, the covalent attachment of ubiquitin-like protein Nedd8, of the Cullin-RING E3 ligase family

- regulates their ubiquitylation activity.

However, regulation of HECT ligases by neddylation has not been reported to date. Here we show that

- the C2-WW-HECT ligase Smurf1 is activated by neddylation.

Smurf1 physically interacts with

- Nedd8 and Ubc12,

- forms a Nedd8-thioester intermediate, and then

- catalyses its own neddylation on multiple lysine residues.

Intriguingly, this autoneddylation needs

- an active site at C426 in the HECT N-lobe.

Neddylation of Smurf1 potently enhances

- ubiquitin E2 recruitment and

- augments the ubiquitin ligase activity of Smurf1.

The regulatory role of neddylation

- is conserved in human Smurf1 and yeast Rsp5.

Furthermore, in human colorectal cancers,

- the elevated expression of Smurf1, Nedd8, NAE1 and Ubc12

- correlates with cancer progression and poor prognosis.

These findings provide evidence that

- neddylation is important in HECT ubiquitin ligase activation and

- shed new light on the tumour-promoting role of Smurf1.

Swinging domains in HECT E3

Subject terms: Biological sciences Cancer Cell biology

Figure 1: Smurf1 expression is elevated in colorectal cancer tissues.

Smurf1 expression is elevated in colorectal cancer tissues.

(a) Smurf1 expression scores are shown as box plots, with the horizontal lines representing the median; the bottom and top of the boxes representing the 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively; and the vertical bars representing the ra

Figure 2: Positive correlation of Smurf1 expression with Nedd8 and its interacting enzymes in colorectal cancer.

Positive correlation of Smurf1 expression with Nedd8 and its interacting enzymes in colorectal cancer

(a) Representative images from immunohistochemical staining of Smurf1, Ubc12, NAE1 and Nedd8 in the same colorectal cancer tumour. Scale bars, 100 μm. (b–d) The expression scores of Nedd8 (b, n=283 ), NAE1 (c, n=281) and Ubc12 (d, n=19…

Figure 3: Smurf1 interacts with Ubc12.

Smurf1 interacts with Ubc12

(a) GST pull-down assay of Smurf1 with Ubc12. Both input and pull-down samples were subjected to immunoblotting with anti-His and anti-GST antibodies. Smurf1 interacted with Ubc12 and UbcH5c, but not with Ubc9. (b) Mapping the regions…

Figure 4: Nedd8 is attached to Smurf1through C426-catalysed autoneddylation.

Nedd8 is attached to Smurf1through C426-catalysed autoneddylation

(a) Covalent neddylation of Smurf1 in vitro.Purified His-Smurf1-WT or C699A proteins were incubated with Nedd8 and Nedd8-E1/E2. Reactions were performed as described in the Methods section. Samples were analysed by western blotting wi…

Figure 5: Neddylation of Smurf1 activates its ubiquitin ligase activity.

Neddylation of Smurf1 activates its ubiquitin ligase activity.

(a) In vivo Smurf1 ubiquitylation assay. Nedd8 was co-expressed with Smurf1 WT or C699A in HCT116 cells (left panels). Twenty-four hours post transfection, cells were treated with MG132 (20 μM, 8 h). HCT116 cells were transfected with…

http://www.nature.com/ncomms/2014/140513/ncomms4733/carousel/ncomms4733-f1.jpg

http://www.nature.com/ncomms/2014/140513/ncomms4733/carousel/ncomms4733-f2.jpg

http://www.nature.com/ncomms/2014/140513/ncomms4733/carousel/ncomms4733-f3.jpg

http://www.nature.com/ncomms/2014/140513/ncomms4733/carousel/ncomms4733-f4.jpg

http://www.nature.com/ncomms/2014/140513/ncomms4733/carousel/ncomms4733-f5.jpg

http://www.nature.com/ncomms/2014/140513/ncomms4733/carousel/ncomms4733-f6.jpg

http://www.nature.com/ncomms/2014/140513/ncomms4733/carousel/ncomms4733-f7.jpg

http://www.nature.com/ncomms/2014/140513/ncomms4733/carousel/ncomms4733-f8.jpg

The deubiquitylase USP33 discriminates between RALB functions in autophagy and innate immune response

M Simicek, S Lievens, M Laga, D Guzenko, VN. Aushev, et al.

Nature Cell Biology 2013; 15, 1220–1230 http://dx.doi.org:/10.1038/ncb2847

The RAS-like GTPase RALB mediates cellular responses to nutrient availability or viral infection by respectively

- engaging two components of the exocyst complex, EXO84 and SEC5.

- RALB employs SEC5 to trigger innate immunity signalling, whereas

- RALB–EXO84 interaction induces autophagocytosis.

How this differential interaction is achieved molecularly by the RAL GTPase remains unknown.

We found that whereas GTP binding

ubiquitylation of RALB at Lys 47

- tunes its activity towards a particular effector.

Specifically, ubiquitylation at Lys 47

- sterically inhibits RALB binding to EXO84, while

- facilitating its interaction with SEC5.

Double-stranded RNA promotes

- RALB ubiquitylation and

- SEC5–TBK1 complex formation.

In contrast, nutrient starvation

- induces RALB deubiquitylation

- by accumulation and relocalization of the deubiquitylase USP33

- to RALB-positive vesicles.

Deubiquitylated RALB

- promotes the assembly of the RALB–EXO84–beclin-1 complexes

- driving autophagosome formation. Thus,

- ubiquitylation within the effector-binding domain

- provides the switch for the dual functions of RALB in

- autophagy and innate immune responses.

Part 5. Metabolic Syndrome

Single Enzyme is Necessary for Development of Diabetes

Published: Aug 20, 2014 http://www.technologynetworks.com/Metabolomics/news.aspx?ID=169416

12-LO enzyme promotes the obesity-induced oxidative stress in the pancreatic cells.

An enzyme called 12-LO promotes the obesity-induced oxidative stress in the pancreatic cells that leads

- to pre-diabetes, and diabetes.

12-LO’s enzymatic action is the last step in

- the production of certain small molecules that harm the cell,

according to a team from Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis.

The findings will enable the development of drugs that can interfere with this enzyme, preventing or even reversing diabetes. The research is published ahead of print in the journal Molecular and Cellular Biology.

In earlier studies, these researchers and their collaborators at Eastern Virginia Medical School showed that

- 12-LO (which stands for 12-lipoxygenase) is present in these cells

- only in people who become overweight.

The harmful small molecules resulting from 12-LO’s enzymatic action are known as HETEs, short for hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid.

- HETEs harm the mitochondria, which then

- fail to produce sufficient energy to enable

- the pancreatic cells to manufacture the necessary quantities of insulin.

For the study, the investigators genetically engineered mice that

- lacked the gene for 12-LO exclusively in their pancreas cells.

Mice were either fed a low-fat or high-fat diet.

Both the control mice and the knockout mice on the high fat diet

- developed obesity and insulin resistance.

The investigators also examined the pancreatic beta cells of both knockout and control mice, using both microscopic studies and molecular analysis. Those from the knockout mice were intact and healthy, while

- those from the control mice showed oxidative damage,

- demonstrating that 12-LO and the resulting HETEs

- caused the beta cell failure.

Mirmira notes that fatty diet used in the study was the Western Diet, which comprises mostly saturated-“bad”-fats. Based partly on a recent study of related metabolic pathways, he says that

- the unsaturated and mono-unsaturated fats-which comprise most fats in the healthy,

- relatively high fat Mediterranean diet-are unlikely to have the same effects.

“Our research is the first to show that 12-LO in the beta cell

- is the culprit in the development of pre-diabetes, following high fat diets,” says Mirmira.

“Our work also lends important credence to the notion that

- the beta cell is the primary defective cell in virtually all forms of diabetes and pre-diabetes.”

A New Player in Lipid Metabolism Discovered

Published: Aug18, 2014 http://www.technologynetworks.com/Metabolomics/news.aspx?ID=169356

Specially engineered mice gained no weight, and normal counterparts became obese

- on the same high-fat, obesity-inducing Western diet.

Specially engineered mice that lacked a particular gene did not gain weight

- when fed a typical high-fat, obesity-inducing Western diet.

Yet, these mice ate the same amount as their normal counterparts that became obese.

The mice were engineered with fat cells that lacked a gene called SEL1L,

- known to be involved in the clearance of mis-folded proteins

- in the cell’s protein making machinery called the endoplasmic reticulum (ER).

When mis-folded proteins are not cleared but accumulate,

- they destroy the cell and contribute to such diseases as

- mad cow disease,

- Type 1 diabetes and

- cystic fibrosis.

“The million-dollar question is why don’t these mice gain weight? Is this related to its inability to clear mis-folded proteins in the ER?” said Ling Qi, associate professor of molecular and biochemical nutrition and senior author of the study published online July 24 in Cell Metabolism. Haibo Sha, a research associate in Qi’s lab, is the paper’s lead author.

Interestingly, the experimental mice developed a host of other problems, including

- postprandial hypertriglyceridemia,

- and fatty livers.

“Although we are yet to find out whether these conditions contribute to the lean phenotype, we found that

- there was a lipid partitioning defect in the mice lacking SEL1L in fat cells,

- where fat cells cannot store fat [lipids], and consequently

- fat goes to the liver.

During the investigation of possible underlying mechanisms, we discovered

- a novel function for SEL1L as a regulator of lipid metabolism,” said Qi.

Sha said “We were very excited to find that

- SEL1L is required for the intracellular trafficking of

- lipoprotein lipase (LPL), acting as a chaperone,” .

and added that “Using several tissue-specific knockout mouse models,

- we showed that this is a general phenomenon,”

Without LPL, lipids remain in the circulation;

- fat and muscle cells cannot absorb fat molecules for storage and energy combustion,

People with LPL mutations develop

- postprandial hypertriglyceridemia similar to

- conditions found in fat cell-specific SEL1L-deficient mice, said Qi.

Future work will investigate the

- role of SEL1L in human patients carrying LPL mutations and

- determine why fat cell-specific SEL1L-deficient mice remain lean under Western diets, said Sha.

Co-authors include researchers from Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles; Wageningen University in the Netherlands; Georgia State University; University of California, Los Angeles; and the Medical College of Soochow University in China.

The study was funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health, the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development National Institutes of Health, the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Chinese National Science Foundation, the American Diabetes Association, Cornell’s Center for Vertebrate Genomics and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Part 6. Biomarkers

Biomarkers Take Center Stage

Josh P. Roberts

GEN May 1, 2013 (Vol. 33, No. 9) http://www.genengnews.com/

While work with biomarkers continues to grow, scientists are also grappling with research-related bottlenecks, such as

- affinity reagent development,

- platform reproducibility, and

- sensitivity.

Biomarkers by definition indicate some state or process that generally occurs

- at a spatial or temporal distance from the marker itself, and

it would not be an exaggeration to say that biomedicine has become infatuated with them:

- where to find them,

- when they may appear,

- what form they may take, and

- how they can be used to diagnose a condition or

- predict whether a therapy may be successful.

Biomarkers are on the agenda of many if not most industry gatherings, and in cases such as Oxford Global’s recent “Biomarker Congress” and the GTC “Biomarker Summit”, they hold the naming rights. There, some basic principles were built upon, amended, and sometimes challenged.

In oncology, for example, biomarker discovery is often predicated on the premise that

- proteins shed from a tumor will traverse to and persist in, and be detectable in, the circulation.

By quantifying these proteins—singularly or as part of a larger “signature”—the hope is

- to garner information about the molecular characteristics of the cancer

- that will help with cancer detection and

- personalization of the treatment strategy.

Yet this approach has not yet turned into the panacea that was hoped for. Bottlenecks exist in

- affinity reagent development,

- platform reproducibility, and

- sensitivity.

There is also a dearth of understanding of some of the

- fundamental principles of biomarker biology that we need to know the answers to,

said Parag Mallick, Ph.D., whose lab at Stanford University is “working on trying to understand where biomarkers come from.”

There are dogmas saying that

- circulating biomarkers come solely from secreted proteins.

But Dr. Mallick’s studies indicate that fully

- 50% of circulating proteins may come from intracellular sources or

- proteins that are annotated as such.

“We don’t understand the processes governing

- which tumor-derived proteins end up in the blood.”

Other questions include “how does the size of a tumor affect how much of a given protein will be in the blood?”—perhaps

- the tumor is necrotic at the center, or

- it’s hypervascular or hypovascular.

He points out “The problem is that these are highly nonlinear processes at work, and

- there is a large number of factors that might affect the answer to that question,” .

Their research focuses on using

- mass spectrometry and

- computational analysis

- to characterize the biophysical properties of the circulating proteome, and

- relate these to measurements made of the tumor itself.

Furthermore, he said – “We’ve observed that the proteins that are likely to

- first show up and persist in the circulation, ..

- are more stable than proteins that don’t,”

- “we can quantify how significant the effect is.”

The goal is ultimately to be able to

- build rigorous, formal mathematical models that will allow something measured in the blood

- to be tied back to the molecular biology taking place in the tumor.

And conversely, to use those models

- to predict from a tumor what will be found in the circulation.

“Ultimately, the models will allow you to connect the dots between

- what you measure in the blood and the biology of the tumor.”

Bound for Affinity Arrays

Affinity reagents are the main tools for large-scale protein biomarker discovery. And while this has tended to mean antibodies (or their derivatives), other affinity reagents are demanding a place in the toolbox.

Affimers, a type of affinity reagent being developed by Avacta, consist of

- a biologically inert, biophysically stable protein scaffold

- containing three variable regions into which

- distinct peptides are inserted.

The resulting three-dimensional surface formed by these peptides

- interacts and binds to proteins and other molecules in solution,

- much like the antigen-binding site of antibodies.

Unlike antibodies, Affimers are relatively small (13 KDa),

- non-post-translationally modified proteins

- that can readily be expressed in bacterial culture.

They may be made to bind surfaces through unique residues

- engineered onto the opposite face of the Affimer,

- allowing the binding site to be exposed to the target in solution.

“We don’t seem to see in what we’ve done so far

- any real loss of activity or functionality of Affimers when bound to surfaces—

they’re very robust,” said CEO Alastair Smith, Ph.D.

Avacta is taking advantage of this stability and its large libraries of Affimers to develop

- very large affinity microarrays for

- drug and biomarker discovery.

To date they have printed arrays with around 20–25,000 features, and Dr. Smith is “sure that we can get toward about 50,000 on a slide,” he said. “There’s no real impediment to us doing that other than us expressing the proteins and getting on with it.”

Customers will be provided with these large, complex “naïve” discovery arrays, readable with standard equipment. The plan is for the company to then “support our customers by providing smaller arrays with

- the Affimers that are binding targets of interest to them,” Dr. Smith foretold.

And since the intellectual property rights are unencumbered,

- Affimers in those arrays can be licensed to the end users

- to develop diagnostics that can be validated as time goes on.

Around 20,000-Affimer discovery arrays were recently tested by collaborator Professor Ann Morgan of the University of Leeds with pools of unfractionated serum from patients with symptoms of inflammatory disease. The arrays

- “rediscovered” elevated C-reactive protein (CRP, the clinical gold standard marker)

- as well as uncovered an additional 22 candidate biomarkers.

- other candidates combined with CRP, appear able to distinguish between different diseases such as

- rheumatoid arthritis,

- psoriatic arthritis,

- SLE, or

- giant cell arteritis.

Epigenetic Biomarkers

Sometimes biomarkers are used not to find disease but

- to distinguish healthy human cell types, with

- examples being found in flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry.

These widespread applications, however, are difficult to standardize, being

- subject to arbitrary or subjective gating protocols and other imprecise criteria.

Epiontis instead uses an epigenetic approach. “What we need is a unique marker that is

- demethylated only in one cell type and

- methylated in all the other cell types,”

Each cell of the right cell type will have

- two demethylated copies of a certain gene locus,

- allowing them to be enumerated by quantitative PCR.

The biggest challenge is finding that unique epigenetic marker. To do so they look through the literature for proteins and genes described as playing a role in the cell type’s biology, and then

- look at the methylation patterns to see if one can be used as a marker,

They also “use customized Affymetrix chips to look at the

- differential epigenetic status of different cell types on a genomewide scale.”

explained CBO and founder Ulrich Hoffmueller, Ph.D.

The company currently has a panel of 12 assays for 12 immune cell types. Among these is an assay for

- regulatory T (Treg) cells that queries the Foxp3 gene—which is uniquely demethylated in Treg

- even though it is transiently expressed in activated T cells of other subtypes.

Also assayed are Th17 cells, difficult to detect by flow cytometry because

- “the cells have to be stimulated in vitro,” he pointed out.

Developing New Assays for Cancer Biomarkers

Researchers at Myriad RBM and the Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas are collaborating to develop

- new assays for cancer biomarkers on the Myriad RBM Multi-Analyte Profile (MAP) platform.

The release of OncologyMAP 2.0 expanded Myriad RBM’s biomarker menu to over 250 analytes, which can be measured from a small single sample, according to the company. Using this menu, L. Stephen et al., published a poster, “Analysis of Protein Biomarkers in Prostate and Colorectal Tumor Lysates,” which showed the results of

- a survey of proteins relevant to colorectal (CRC) and prostate (PC) tumors

- to identify potential proteins of interest for cancer research.

The study looked at CRC and PC tumor lysates and found that 102 of the 115 proteins showed levels above the lower limit of quantification.

- Four markers were significantly higher in PC and 10 were greater in CRC.

For most of the analytes, duplicate sections of the tumor were similar, although some analytes did show differences. In four of the CRC analytes, tumor number four showed differences for CEA and tumor number 2 for uPA.

Thirty analytes were shown to be

- different in CRC tumor compared to its adjacent tissue.

- Ten of the analytes were higher in adjacent tissue compared to CRC.

- Eighteen of the markers examined demonstrated —-

significant correlations of CRC tumor concentration to serum levels.

“This suggests.. that the Oncology MAP 2.0 platform “provides a good method for studying changes in tumor levels because many proteins can be assessed with a very small sample.”

Clinical Test Development with MALDI-ToF

While there have been many attempts to translate results from early discovery work on the serum proteome into clinical practice, few of these efforts have progressed past the discovery phase.

Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight (MALDI-ToF) mass spectrometry on unfractionated serum/plasma samples offers many practical advantages over alternative techniques, and does not require

- a shift from discovery to development and commercialization platforms.

Biodesix claims it has been able to develop the technology into

- a reproducible, high-throughput tool to

- routinely measure protein abundance from serum/plasma samples.

“.. we improved data-analysis algorithms to

- reproducibly obtain quantitative measurements of relative protein abundance from MALDI-ToF mass spectra.

Heinrich Röder, CTO points out that the MALDI-ToF measurements

- are combined with clinical outcome data using

- modern learning theory techniques

- to define specific disease states

- based on a patient’s serum protein content,”

The clinical utility of the identification of these disease states can be investigated through a retrospective analysis of differing sample sets. For example, Biodesix clinically validated its first commercialized serum proteomic test, VeriStrat®, in 85 different retrospective sample sets.

Röder adds that “It is becoming increasingly clear that

- the patients whose serum is characterized as VeriStrat Poor show

- consistently poor outcomes irrespective of

- tumor type,

- histology, or

- molecular tumor characteristics,”

MALDI-ToF mass spectrometry, in its standard implementation,

- allows for the observation of around 100 mostly high-abundant serum proteins.

Further, “while this does not limit the usefulness of tests developed from differential expression of these proteins,

- the discovery potential would be greatly enhanced

- if we could probe deeper into the proteome

- while not giving up the advantages of the MALDI-ToF approach,”

Biodesix reports that its new MALDI approach, Deep MALDI™, can perform

- simultaneous quantitative measurement of more than 1,000 serum protein features (or peaks) from 10 µL of serum in a high-throughput manner.

- it increases the observable signal noise ratio from a few hundred to over 50,000,

- resulting in the observation of many lower-abundance serum proteins.

Breast cancer, a disease now considered to be a collection of many complexes of symptoms and signatures—the dominant ones are labeled Luminal A, Luminal B, Her2, and Basal— which suggests different prognose, and

- these labels are considered too simplistic for understanding and managing a woman’s cancer.

Studies published in the past year have looked at

- somatic mutations,

- gene copy number aberrations,

- gene expression abnormalities,

- protein and miRNA expression, and

- DNA methylation,

coming up with a list of significantly mutated genes—hot spots—in different categories of breast cancers. Targeting these will inevitably be the focus of much coming research.

“We’ve been taking these large trials and profiling these on a variety of array or sequence platforms. We think we’ll get

- prognostic drivers

- predictive markers for taxanes and

- monoclonal antibodies and

- tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors,”

explained Brian Leyland-Jones, Ph.D., director of Edith Sanford Breast Cancer Research. “We will end up with 20–40 different diseases, maybe more.”

Edith Sanford Breast Cancer Research is undertaking a pilot study in collaboration with The Scripps Research Institute, using a variety of tests on 25 patients to see how the information they provide complements each other, the overall flow, and the time required to get and compile results.

Laser-captured tumor samples will be subjected to low passage whole-genome, exome, and RNA sequencing (with targeted resequencing done in parallel), and reverse-phase protein and phosphorylation arrays, with circulating nucleic acids and circulating tumor cells being queried as well. “After that we hope to do a 100- or 150-patient trial when we have some idea of the best techniques,” he said.

Dr. Leyland-Jones predicted that ultimately most tumors will be found

- to have multiple drivers,

- with most patients receiving a combination of two, three, or perhaps four different targeted therapies.

Reduce to Practice

According to Randox, the evidence Investigator is a sophisticated semi-automated biochip system designed for research, clinical, forensic, and veterinary applications.