Nitric Oxide Function in Coagulation – Part II

Curator and Author: Larry H. Bernstein, MD, FCAP

Subtitle: Nitric oxide in hemostatic and bleeding mechanisms. Part II.

Summary: This is the second of a coagulation series on PharmaceuticalIntelligence(wordpress.com) treating the diverse effects of NO on platelets, the coagulation cascade, and protein-membrane interactions with low flow states, local and systemic inflammatory disease, oxidative stress, and hematologic disorders. It is highly complex as the distinction between intrinsic and extrinsic pathways become blurred as a result of endothelial shear stress, distinctly different than penetrating or traumatic injury. In addition, other factors that come into play are also considered.

Please refer to Part I.

Coagulation Pathway

The workhorse tests of the modern coagulation laboratory, the prothrombin time (PT) and the activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), are the basis for the published extrinsic and intrinsic coagulation pathways. This is, however, a much simpler model than one encounters delving into the mechanism and interactions involved in hemostasis and thrombosis, or in hemorrhagic disorders.

We first note that there are three components of the hemostatic system in all vertebrates:

- Platelets,

- vascular endothelium, and

- plasma proteins.

The liver is the largest synthetic organ, which synthesizes

- albumin,

- acute phase proteins,

- hormonal and metal binding proteins,

- albumin,

- IGF-1, and

- prothrombin, mainly responsible for the distinction between plasma and serum (defibrinated plasma).

Role of vascular endothelium.

I have identified the importance of prothrombin, thrombin, and the divalent cation Ca 2+ (1% of the total body pool), mention of heparin action, and of vitamin K (inhibited by warfarin). Endothelial functions are inherently related to procoagulation and anticoagulation. The subendothelial matrix is a complex of many materials, most important related to coagulation being collagen and von Willebrand factor.

What about extrinsic and intrinsic pathways? Tissue factor, when bound to factor VIIa, is the major activator of the extrinsic pathway of coagulation. Classically, tissue factor is not present in the plasma but only presented on cell surfaces at a wound site, which is “extrinsic” to the circulation. Or is it that simple?

Endothelium is the major synthetic and storage site for von Willebrand factor (vWF). vWF is…

- secreted from the endothelial cell both into the plasma and also

- abluminally into the subendothelial matrix, and

- acts as the intercellular glue binding platelets to one another and also to the subendothelial matrix at an injury site.

- acts as a carrier protein for factor VIII (antihemophilic factor).

- It binds to the platelet glycoprotein Ib/IX/V receptor and

- mediates platelet adhesion to the vascular wall under shear. [Lefkowitz JB. Coagulation Pathway and Physiology. Chapter I. in Hemostasis Physiology. In ( ???), pp1-12].

Ca++ and phospholipids are necessary for all of the reactions that result in the activation of prothrombin to thrombin. Coagulation is initiated by an extrinsic mechanism that

- generates small amounts of factor Xa, which in turn

- activates small amounts of thrombin.

The tissue factor/factorVIIa proteolysis of factor X is quickly inhibited by tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI).The small amounts of thrombin generated from the initial activation feedback

- to create activated cofactors, factors Va and VIIIa, which in turn help to

- generate more thrombin.

- Tissue factor/factor VIIa is also capable of indirectly activating factor X through the activation of factor IX to factor IXa.

- Finally, as more thrombin is created, it activates factor XI to factor XIa, thereby enhancing the ability to ultimately make more thrombin.

The reconceptualization of hemostasis

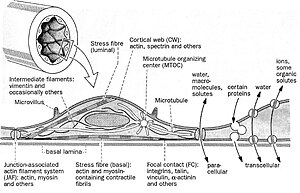

The common theme in activation and regulation of plasma coagulation is the reduction in dimensionality. Most reactions take place in a 2D world that will increase the efficiency of the reactions dramatically. The localization and timing of the coagulation processes are also dependent on the formation of protein complexes on the surface of membranes. The coagulation processes can also be controlled by certain drugs that destroy the membrane binding ability of some coagulation proteins – these proteins will be lost in the 3D world and not able to form procoagulant complexes on surfaces.

Assembly of proteins on membranes – making a 3D world flat

• The timing and efficiency of coagulation processes are handled by reduction in dimensionality

– Make 3 dimensions to 2 dimensions

• Coagulation proteins have membrane binding capacity

• Membranes provide non-coagulant and procoagulant surfaces

– Intact cells/activated cells

• Membrane binding is a target for anticoagulant drugs

– Anti-vitamin K (e.g. warfarin)

Modern View

It can be divided into the phases of initiation, amplification and propagation.

- In the initiation phase, small amounts of thrombin can be formed after exposure of tissue factor to blood.

- In the amplification phase, the traces of thrombin will be inactivated or used for amplification of the coagulation process.

At this stage there is not enough thrombin to form insoluble fibrin. In order to proceed further thrombin activates platelets, which provide a procoagulant surface for the coagulation factors. Thrombin will also activate the vital cofactors V and VIII that will assemble on the surface of activated platelets. Thrombin can also activate factor XI, which is important in a feedback mechanism.

In the final step, the propagation phase, the highly efficient tenase and prothrombinase complexes have been assembled on the membrane surface. This yields large amounts of thrombin at the site of injury that can cleave fibrinogen to insoluble fibrin. Factor XI activation by thrombin then activates factor IX, which leads to the formation of more tenase complexes. This ensures enough thrombin is formed, despite regulation of the initiating TF-FVIIa complex, thus ensuring formation of a stable fibrin clot. Factor XIII stabilizes the fibrin clot through crosslinking when activated by thrombin.

Platelet Aggregation

The activities of adenylate and guanylate cyclase and cyclic nucleotide 3′:5′-phosphodiesterase were determined during the aggregation of human blood platelets with

- thrombin, ADP,

- arachidonic acid and

- epinephrine.

[Aggregation is dependent on an intact release mechanism since inhibition of aggregation occurred with adenosine, colchicine, or EDTA. (Herman GE, Seegers WH, Henry RL. Autoprothrombin ii-a, thrombin, and epinephrine: interrelated effects on platelet aggregation. Bibl Haematol 1977;44:21-7)].

- The platelet guanylate cyclase activity during aggregation depends on the nature and mode of action of the inducing agent.

- The membrane adenylate cyclase activity during aggregation is independent of the aggregating agent and is associated with a reduction of activity and

- Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase remains unchanged during the process of platelet aggregation and release.

The role of platelets in arterial thrombosis

Formation of a thrombus on a ruptured plaque is the product of a complex interaction between coagulation factors in the plasma and platelets.

- Tissue factor (TF) released from the subendothelial tissue after endothelial damage induces a cascade of activation of coagulation factors ultimately leading to the formation of thrombin.

- Thrombin cleaves fibrinogen to fibrin, which assembles into a mesh that supports the platelet aggregates.

The Platelet

The platelets are …

- anucleated,

- discoid shaped cell fragments

- originating from megakaryocytes

- fragmented as they are released from the bone marrow

Whether they can in circumstances be developed at extramedullary sites (liver sinusoid) is another matter. They have a lifespan of 7-10 days. Of special interest is:

- They have a network of internal membranes forming a dense tubular system and the open canalicular system (OCS).

- The plasma membrane is an extension of the OCS, thereby greatly increasing the surface area of the platelet.

- The dense tubular system is comparable to the endoplasmatic reticulum in other cell types and is the main storage place of the majority of the platelet’s Ca2+.

Three types of secretory granules exist in platelets:

- the dense granules

- In the dense granules serotonin

- adenosine diphosphate (ADP) and

- Ca2+ are stored.

- a-granules contain

- P-selectin,

- fibrinogen,

- thrombospondin,

- Von Willebrand Factor,

- platelet factor 4 and

- platelet derived growth factor

- lysosomes.

Circulating platelets are kept in a resting state by endothelial cell derived

- prostacyclin (PGI2) and

- nitric oxide (NO).

PGI2 increases cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), the most potent platelet inhibitor.

Contact activation

The major regulator of the activation of the contact system is the plasma protease inhibitor, C1-INH, which inhibits activated fXII, kallikrein and fXIa. In addition, α2-macroglobulin is an important inhibitor of kallikrein and α1-antitrypsin for fXIa. Factor XII also converts the fXI to an active enzyme, fXIa, which, in turn, converts fIX to fIXa, thereby activating the intrinsic pathway of coagulation.

Activation

Several agonists can activate platelets;

- ADP,

- collagen,

- thromboxane A2 (TxA2),

- epinephrin,

- serotonine and

- thrombin,

which lead to activation previously referred to:

- platelet shape change is

- followed by aggregation and

- granule secretion.

Upon activation the discoid shape changes into a spherical form.

Activation of platelets is increased by two positive feedback loops

- arachidonic acid is cleaved from phospholipids and transformed by cyclooxygenase

(COX) to prostaglandin G2 and H2,

- followed by the formation of TxA2, a potent platelet agonist.

2. the secretion of ADP by the dense granules,

- resulting in activation of the ADP receptor P2Y12.

This causes inhibition of cyclic AMP and sustained aggregation.

Aggregation

The integrin receptor αIIbβ3 plays a vital role in platelet aggregation. The platelet agonists

- induce a conformational change of the αIIbβ3 receptor and

- exposition of binding domains for fibrinogen and von Willebrand Factor.

This allows cross-linking of platelets and the formation of aggregates.

In addition to shape change and aggregation, the membranes of the α- and dense granules fuse with the membranes of the OCS. This causes the release of their contents and the transportation of proteins embedded in their membrane to the plasma membrane.

This complex interaction between

- endothelial cells

- clotting factors

- platelets and

- other factors and cells

can be studied in both in vitro and in vivo model systems. The disadvantage of in vitro assays is that it studies the role of a certain protein or cell in isolation. Given the large number of participants and the complex interactions of thrombus formation there is need to study thrombosis and hemostasis in intact living animals, with all the components important for thrombus formation – a vessel wall and flowing blood – present.

Endothelial Damage and Role as “Primer”

- Endothelial injury changes the permeability of the arterial wall.

- This is followed by an influx of low-density lipoprotein (LDL).

- This elicits an inflammatory response in the vascular wall.

- Monocytes and T-cells bind to the endothelial cells promoting increased migration of the cells into the intima layer

- The monocytes differentiate into macrophages, which take up modified lipoproteins and transform them into foam cells.

- Concurrent with this process macrophages produce cytokines and proteases.

This is a vicious circle of lipid driven inflammation that leads to narrowing of the vessel’s lumen without early clinical consequences. Clinical manifestations of more advanced atherosclerotic disease are caused by destabilization of an atherosclerotic plaque formed as described.

- The first recognizable lesion of the stable atherosclerotic plaque is the fatty streak, which consists of the above described foam cells and T-lymphocytes in the intima.

- Further development of the lesion leads to the intermediate lesion, composed

- of layers of macrophages and smooth muscle cells.

- A more advanced stage is called the vulnerable plaque.

- It has a large lipid core that is covered by a thin fibrous cap.

- This cap separates the lipid contents of the plaque from the circulating blood.

- The vulnerable plaque is prone to rupture, resulting in the formation of a thrombus on the site of disruption or the thrombus can be superimposed on plaque erosion without signs of plaque rupture.

The formation of a superimposed thrombus on a disrupted atherosclerotic plaque in the lumen of the artery leads to

- an acute occlusion of the vessel

- hypoxia of the downstream tissue.

Depending on the location of the atherosclerotic plaque this will cause a myocardial infarction, stroke or peripheral vascular disease.

Endothelial regulation of coagulation

The endothelium attenuates platelet activity by releasing

- nitric oxide and

- prostacyclin.

Several coagulation inhibitors are produced by endothelial cells.

Endothelium-derived TFPI (on its surface) is rapidly released into circulation after heparin administration, reducing the pro-coagulant activities of TF-fVIIa. Endothelial cells also secrete heparin-sulphate, a glycosaminoglycan which catalyzes anti-coagulant activity of AT. Plasma AT binds to heparin-sulphate located on the luminal surface and in the basement membrane of the endothelium. Thrombomodulin is another endothelium-bound protein with anti-coagulant and anti-inflammatory functions. In response to systemic pro-coagulant stimuli, tissue-type plasminogen activator (tPA) is transiently released from the Weibel-Palade bodies of endothelial cells to promote fibrinolysis. Downstream of the vascular injury, the complex of TF-fVIIa/fXa is inhibited by TFPI. Plasma (free) fXa and thrombin are rapidly neutralized by heparan-bound AT. Thrombin is also taken up by endothelial surface-bound thrombomodulin.

The protein C pathway works in hemostasis to control thrombin formation in the area surrounding the clot. Thrombin, generated via the coagulation pathway, is localized to the endothelium by binding to the integral membrane protein, thrombomodulin (TM). TM by occupying exosite I on thrombin, which is required for fibrinogen binding and cleavage, reduces thrombin’s pro-coagulant activities. TM bound thrombin on the endothelial cell surface is able to cleave PC producing activated protein C (APC), a serine protease. In the presence of protein S, APC inactivates FVa and FVIIIa. The proteolytic activity of APC is regulated predominantly by a protein C inhibitor.

Fibrinolytic pathway

Fibrinolysis is the physiological breakdown of fibrin to limit and resolve blood clots. Fibrin is degraded primarily by the serine protease, plasmin, which circulates as plasminogen. In an auto-regulatory manner, fibrin serves as both the co-factor for the activation of plasminogen and the substrate for plasmin. In the presence of fibrin, tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) cleaves plasminogen producing plasmin, which proteolyzes the fibrin. This reaction produces the protein fragment D-dimer, which is a useful marker of fibrinolysis, and a marker of thrombin activity because fibrin is cleaved from fibrinogen to fibrin.

Nitric Oxide and Platelet Energy Production

Nitric oxide (NO) has been increasingly recognized as an important intra- and intercellular messenger molecule with a physiological role in

- vascular relaxation

- platelet physiology

- neurotransmission and

- immune responses.

In vitro NO is a strong inhibitor of platelet adhesion and aggregation. In the blood stream, platelets remain in contact with NO that is permanently released from the endothelial cells and from activated macrophages. It has been suggested that the activated platelet itself is able to produce NO. It has been proposed that the main intracellular target for NO in platelets is soluble cytosolic guanylate cyclase. NO activates the enzyme. When activated, intracellular cGMP elevation inhibits platelet activation. Further, elevated cGMP may not be the sole factor directly involved in the inhibition of platelet activation.

Platelets are fairly active metabolically and have a total ATP turnover rate of about 3–8 times that of resting mammalian muscle. Platelets contain mitochondria which enable these cells to produce energy both in the oxidative and anaerobic pathways.

- Under aerobic conditions, ATP is produced by aerobic glycolysis which can account for 30–50% of total ATP production,

- by oxidative metabolism using glucose and glycogen (6–11%), amino-acids (7%) or free fatty acids (20–40%).

The inhibition of mitochondrial respiration by removing oxygen or by respiratory chain blockers (antimycin A, cyanide, rotenone) results in the stimulation of glycolytic flux. This phenomenon indicates that in platelets glycolysis and mitochondrial respiration are tightly functionally connected. It has been reported that the activation of human platelets by high concentration of thrombin is accompanied by an acceleration of lactate production and an increase in oxygen consumption.

The results (in porcine platelets) indicate that:

- NO is able to diminish mitochondrial energy production through the inhibition of cytochrome oxidase

- The inhibitory effect of NO on platelet secretion (but not aggregation) can be attributed to the reduction of mitochondrial energy production.

Porcine blood platelets stimulated by collagen produce more lactate. This indicates that both glycolytic and oxidative ATP production supports platelet responses, and blocking of energy production in platelets may decrease their responses. It is well established that platelet responses have different metabolic energy (ATP) requirements increasing in the order:

- Aggregation

- < dense and alfa granule secretion

- < acid hydrolase secretion.

In addition, exogenously added NO (in the form of NO donors) stimulates glycolysis in intact porcine platelets. Since in platelets glycolysis and mitochondrial respiration are tightly functionally connected, this indicates the stimulatory effect of NO on glycolysis in intact platelets may be produced by non-functional mitochondria.

Can this be the case?

- NO donors are able to inhibit both mitochondrial respiration and platelet cytochrome oxidase.

- Interestingly, the concentrations of NO donors inhibiting mitochondrial respiration and cytochrome oxidase were similar to those stimulating glycolysis in intact platelets.

Studies have shown that mitochondrial complex I is inhibited only after a prolonged (6–18 h) exposure to NO and

- This inhibition appears to result from S-nitrosylation of critical thiols in the enzyme complex.

- Further studies are needed to establish whether long term exposure of platelets to NO affects Mitochondrial complexes I and II.

Comparison of the concentrations of SNAP and SNP affecting cytochrome oxidase activity and mitochondrial respiration with those reducing the platelet responses indicates that NO does not reduce platelet aggregation through the inhibition of oxidative energy production. The concentrations of the NO donors inhibiting platelet secretion, mitochondrial respiration and cytochrome oxidase were similar. Thus, the platelet release reaction strongly depends on the oxidative energy production, and in porcine platelets NO inhibits mitochondrial energy production at the step of cytochrome oxidase.

Taking into account that platelets may contain NO synthase and are able to produce significant amounts of NO it seems possible that nitric oxide can function in these cells as a physiological regulator of mitochondrial energy production.

Key words: glycolysis, mitochondrial energy production, nitric oxide, porcine platelets.

Abbreviations: NO, nitric oxide; SNAP, S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicyllamine; SNP, sodium nitroprusside.

[M Tomasiak, H Stelmach, T Rusak and J Wysocka. Nitric oxide and platelet energy metabolism. Acta Biochimica Polonica 2004; 51(3):789–803.]

Nitric Oxide and Platelet Adhesion

The adhesion of human platelets to monolayers of bovine endothelial cells in culture was studied to determine the role of endothelium-derived nitric oxide in the regulation of platelet adhesion. The adhesion of unstimulated and thrombin-stimulated platelets, washed and labelled with indium-111, was lower in the presence than in the absence of bradykinin or exogenous nitric oxide. The inhibitory action of both bradykinin and nitric oxide was abolished by hemoglobin, but not by aspirin, and was potentiated by superoxide dismutase to a similar degree. It appears that the effect of bradykinin is mediated by the release of nitric oxide from the endothelial cells, and that nitric oxide release contributes to the non-adhesive properties of vascular endothelium.

(Radomski MW, Palmer RMJ, Moncada S. Endogenous Nitric Oxide Inhibits Human Platelet Adhesion to Vascular Endothelium. The Lancet 1987 330; 8567(2): 1057–1058.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(87)91481-4)

1 The interactions between endothelium-derived nitric oxide (NO) and prostacyclin as inhibitors of platelet aggregation were examined to determine whether release of NO accounts for the inhibition of platelet aggregation attributed to EDRF.

2 Porcine aortic endothelial cells treated with indomethacin and stimulated with bradykinin (10-100 nM) released NO in quantities sufficient to account for the inhibition of platelet aggregation attributed to endothelium-derived relaxing factor (EDRF).

3 In the absence of indomethacin, stimulation of the cells with bradykinin (1-3 nM) released small amounts of prostacyclin and EDRF which synergistically inhibited platelet aggregation.

4 EDRF and authentic NO also caused disaggregation of platelets aggregated either with collagen or with U46619.

5 A reciprocal potentiation of both the anti- and the disaggregating activity was also observed between low concentrations of prostacyclin and authentic NO or EDRF released from endothelial cells.

6 It is likely that interactions between prostacyclin and NO released by the endothelium play a role in the homeostatic regulation of platelet-vessel wall interactions.

(Radomski MW, Palmer RMJ & Moncada S. The anti-aggregating properties of vascular endothelium: interactions between prostacyclin and nitric oxide. Br J Pharmac 1987; 92: 639-646.

Factor Xa–Nitric Oxide Signaling

Although primarily recognized for maintaining the hemostatic balance, blood proteases of the coagulation and fibrinolytic cascades elicit rapid cellular responses in

- vascular

- mesenchymal

- inflammatory cell types.

Considerable effort has been devoted to elucidate the molecular interface between protease-dependent signaling and pleiotropic cellular responses. This led to the identification of several membrane protease receptors, initiating intracellular signal transduction and effector functions in vascular cells. In this context, thrombin receptor activation

- generated second messengers in endothelium and smooth muscle cells,

- released inflammatory cytokines from monocytes, fibroblasts, and endothelium, and

- increased the expression of leukocyte-endothelial cell adhesion molecules.

Similarly, binding of factor Xa to effector cell protease receptor-1 (EPR-1) participated in

- in vivo acute inflammatory responses,

- platelet and brain pericyte prothrombinase activity, and

- endothelial cell and smooth muscle cell signaling and proliferation.

Factor Xa stimulated a 5- to 10-fold increased release of nitric oxide (NO) in a dose-dependent reaction (0.1–2.5 mgyml) unaffected by the thrombin inhibitor hirudin but abolished by active site inhibitors, tick anticoagulant peptide, or Glu-Gly-Arg-chloromethyl ketone. In contrast, the homologous clotting protease factor IXa or another endothelial cell ligand, fibrinogen, was ineffective.

A factor Xa inter-epidermal growth factor synthetic peptide L83FTRKL88(G) blocking ligand binding to effector cell protease receptor-1 inhibited NO release by factor Xa in a dose-dependent manner, whereas a control scrambled peptide KFTGRLL was ineffective.

Catalytically active factor Xa induced hypotension in rats and vasorelaxation in the isolated rat mesentery, which was blocked by the NO synthase inhibitor L-NG-nitroarginine methyl ester (LNAME) but not by D-NAME. Factor Xa/NO signaling also produced a dose-dependent endothelial cell release of interleukin 6 (range 0.55–3.1 ngyml) in a reaction

- inhibited by L-NAME and by the

- inter-epidermal growth factor peptide Leu83–Leu88 but

- unaffected by hirudin.

| We observe that incubation of HUVEC monolayers with factor Xa which resulted in a concentration-dependent release of NO, as determined by cGMP accumulation in these cells, was inhibited by the nitric oxide synthase antagonist L-NAME. |

Catalytically inactive DEGR-factor Xa or TAP-treated factor Xa failed to stimulate NO release by HUVEC.

To determine whether factor Xa-induced NO release could also modulate acute phase/inflammatory cytokine gene expression we examined potential changes in IL-6 release following HUVEC stimulation with factor Xa. HUVEC stimulation with factor Xa resulted in a concentration-dependent release of IL-6.

The specificity of factor Xa-induced cytokine release was investigated. Factor Xa-induced IL-6 release from HUVEC was quantitatively indistinguishable from that obtained with tumor necrosis factor-a or thrombin stimulation. This response was abolished by heat denaturation of factor Xa.

Maximal induction of interleukin 6 mRNA required a brief, 30-min stimulation with factor Xa, and was unaffected by subsequent addition of tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI). These data suggest that factor Xa-induced NO release modulates endothelial cell-dependent vasorelaxation and IL-6 cytokine gene expression.

Here, we find that factor Xa induces the release of endothelial cell NO

This pathway requires a dual step cascade, involving

This pathway requiring factor Xa binding to effector cell protease receptor-1 and a secondary step of ligand-dependent proteolysis may preserve an anti-thrombotic phenotype of endothelium but also trigger acute phase responses during activation of coagulation in vivo. |

In summary, these investigators have identified a signaling pathway centered on the ability of factor Xa to rapidly stimulate endothelial cell NO release. This involves a two-step cascade initiated by catalytic active site-independent binding of factor Xa to its receptor, EPR-1, followed by a second step of ligand dependent proteolysis.

(Papapetropoulos A, Piccardoni P, Cirino G, Bucci M, et al. Hypotension and inflammatory cytokine gene expression triggered by factor Xa–nitric oxide signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. Pharmacology. 1998; 95:4738–4742.)

Platelets and liver disease

Thrombocytopenia is a marked feature of chronic liver disease and cirrhosis. Traditionally, this thrombocytopenia was attributed to passive platelet sequestration in the spleen. More recent insights suggest an increased platelet breakdown and to a lesser extent decreased platelet production plays a more important role. Besides the reduction in number, other studies suggest functional platelet defects. This platelet dysfunction is probably both intrinsic to the platelets and secondary to soluble plasma factors. It reflects not only a decrease in aggregability, but also an activation of the intrinsic inhibitory pathways. (Witters P, Freson K, Verslype C, Peerlinck K, et al. Review article: blood platelet number and function in chronic liver disease and cirrhosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2008; 27: 1017–1029).

The shortcomings of the old Y-shaped model of normal coagulation are nowhere more apparent than in its clinical application to the complex coagulation disorders of acute and chronic liver disease. In this condition, the clotting cascade is heavily influenced by numerous currents and counter-currents resulting in a mixture of pro- and anticoagulant forces that are themselves further subject to change with altered physiological stress such as super-imposed infection or renal failure.

Multiple mechanisms exist for thrombocytopenia common in patients with cirrhosis besides hypersplenism and expected altered thrombopoietin metabolism. Increased production of two important endothelial derived platelet inhibitors

- nitric oxide and

- prostacyclin

may contribute to defective platelet activation in vivo. On the other hand, high plasma levels of vWF in cirrhosis appear to support platelet adhesion.

Reduced levels of coagulation factors V, VII, IX, X, XI, and prothrombin are also commonly observed in liver failure. Vitamin K–dependent clotting factors (II, VII, IX, X) may be defective in function as a result of decreased y-carboxylation (from vitamin K deficiency or intrinsically impaired carboxylase activity). Fibrinogen levels are decreased with advanced cirrhosis and in patients with acute liver failure.

A hyperfibrinolytic state may develop when plasminogen activation by tPA is accelerated on the fibrin surface. Physiologic stress including infection may be key in tipping this process off through increased release of tPA. Not uncommonly, laboratory abnormalities in decompensated cirrhosis come to resemble disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). Relatively stable platelet levels and characteristically high factor VIII levels distinguish this process from DIC as does the absence of uncompensated thrombin generation. The features of both hyperfibrinolysis and DIC are often evident in the decompensated liver disease patient, and the term “accelerated intravascular coagulation and fibrinolysis” (AICF) has been proposed as a way to encapsulate the process under a single heading. The essence of AICF can be postulated to be the result of formation of a fibrin clot that is more susceptible to plasmin degradation due to elevated levels of tPA coupled with inadequate release of PAI to control tPA and lack of a-2 plasmin inhibitor to quench plasmin activity and the maintenance of high local concentrations of plasminogen on clot surfaces despite lower total plasminogen production. These normally balanced processes become pronounced when disturbed by additional stress such as infection.

Normal hemostasis and coagulation is now viewed as primarily a cell-based process wherein key steps in the classical clotting cascade

- occur on the phospholipid membrane surface of cells (especially platelets)

- beginning with activation of tissue factor and factor VII at the site of vascular breach

- which produces an initial “priming” amount of thrombin and a

- subsequent thrombin burst.

Coagulation and hemostasis in the liver failure patient is influenced by multiple, often opposing, and sometimes changing variables. A bleeding diathesis is usually predominant, but the assessment of bleeding risk based on conventional laboratory tests is inherently deficient.

(Caldwell SH, Hoffman M, Lisman T, Gail Macik B, et al. Coagulation Disorders and Hemostasis in Liver Disease: Pathophysiology and Critical Assessment of Current Management. Hepatology 2006;44:1039-1046.)

Bleeding after Coronary Artery bypass Graft

Cardiac surgery with concomitant CPB can profoundly alter haemostasis, predisposing patients to major haemorrhagic complications and possibly early bypass conduit-related thrombotic events as well. Five to seven percent of patients lose more than 2 litres of blood within the first 24 hours after surgery, between 1% and 5% require re-operation for bleeding. Re-operation for bleeding increases hospital mortality 3 to 4 fold, substantially increases post-operative hospital stay and has a sizeable effect on health care costs. Nevertheless, re-exploration is a strong risk factor associated with increased operative mortality and morbidity, including sepsis, renal failure, respiratory failure and arrhythmias.

(Gábor Veres. New Drug Therapies Reduce Bleeding in Cardiac Surgery. Ph.D. Doctoral Dissertation. 2010. Semmelweis University)

Hypercoagulable State in Thalassemia

As the life expectancy of β-thalassemia patients has increased in the last decade, several new complications are being recognized. The presence of a high incidence of thromboembolic events, mainly in thalassemia intermedia patients, has led to the identification of a hypercoagulable state in thalassemia. Patients with thalassemia intermedia (TI) have, in general, a milder clinical phenotype than those with TM and remain largely transfusion independent. The pathophysiology of TI is characterized by extravascular hemolysis, with the release into the peripheral circulation of damaged red blood cells (RBCs) and erythroid precursors because of a high degree of ineffective erythropoiesis. This has also been recently attributed to severe complications such as pulmonary hypertension (PHT) and thromboembolic phenomena.

Many investigators have reported changes in the levels of coagulation factors and inhibitors in thalassemic patients. Prothrombin fragment 1.2 (F1.2), a marker of thrombin generation, is elevated in TI patients. The status of protein C and protein S was investigated in thalassemia in many studies and generally they were found to be decreased; this might be responsible for the occurrence of thromboembolic events in thalassemic patients.

The pathophysiological roles of hemolysis and the dysregulation of nitric oxide homeostasis are correlated with pulmonary hypertension in sickle cell disease and in thalassemia. Nitric oxide binds soluble guanylate cyclase, which converts GTP to cGMP, relaxing vascular smooth muscle and causing vasodilatation. When plasma hemoglobin liberated from intravascularly hemolyzed sickle erythrocytes consumes nitric oxide, the balance is shifted toward vasoconstriction. Pulmonary hypertension is aggravated and in sickle cell disease, it is linked to the intensity of hemolysis. Whether the same mechanism contributes to hypercoagulability in thalassemia is not yet known.

While there are diverse factors contributing to the hypercoagulable state observed in patients with thalassemia. In most cases, a combination of these abnormalities leads to clinical thrombosis. An argument has been made for the a higher incidence of thrombotic events in TI compared to TM patients attributed to transfusion for TM. The higher rate of thrombosis in transfusion-independent TI compared to polytransused TM patients suggests a potential role for transfusions in decreasing the rate of thromboembolic events (TEE). The reduction of TEE in adequately transfused patients may be the result of decreased numbers of pathological RBCs.

(Cappellini MD, Musallam KM, Marcon A, and Taher AT. Coagulopathy in Beta-Thalassemia: Current Understanding and Future Prospects. Medit J Hemat Infect Dis 2009; 1(1):22009029.

DOI 10.4084/MJHID.2009.0292.0), www.mjhid.org/article/view/5250. ISSN 2035-3006.)

Microvascular Endothelial Dysfunction

Severe sepsis, defined as sepsis associated with acute organ dysfunction, results from a generalized inflammatory and procoagulant host response to infection. Coagulopathy in severe sepsis is commonly associated with multiple organ dysfunction, and often results in death. The molecule that is central to these effects is thrombin, although it may also have anticoagulant and antithrombotic effects through the activation of Protein C and induction of prostacyclin. In recent years, it has been recognized that chemicals produced by endothelial cells play a key role in the pathogenesis of sepsis. Thrombomodulin on endothelial cells coverts Protein C to Activated Protein C, which has important antithrombotic, profibrinolytic and anti-inflammatory properties. A number of studies have shown that Protein C levels are reduced in patients with severe infection, or even in inflammatory states without infection. Because coagulopathy is associated with high mortality rates, and animal studies have indicated that therapeutic intervention may result in improved outcomes, it was rational to initiate clinical studies.

Considering the coagulation cascade as a whole, it is the extrinsic pathway (via TF and thrombin activation) rather than the intrinsic pathway that is of primary importance in sepsis. Once coagulation has been triggered by TF activation, leading to thrombin formation, this can have further procoagulant effects, because thrombin itself can activate factors VIII, IX and X. This is normally balanced by the production of anticoagulant factors, such as TF pathway inhibitor, antithrombin and Activated Protein C.

It has been recognized that endothelial cells play a key role in the pathogenesis of sepsis, and that they produce important regulators of both coagulation and inflammation. They can express or release a number of substances, such as TF, endothelin-1 and PAI-1, which promote the coagulation process, as well as other substances, such as antithrombin, thrombomodulin, nitric oxide and prostacyclin, which inhibit it.

Protein C is the source of Activated Protein C. Although Protein C is a biomarker or indicator of sepsis, it has no known specific biological activity. Protein C is converted to Activated Protein C in the presence of normal endothelium. In patients with severe sepsis, the vascular endothelium becomes damaged. The level of thrombomodulin is significantly decreased, and the body’s ability to convert Protein C to Activated Protein C diminishes. Only when activated does Protein C have antithrombotic, profibrinolytic and anti-inflammatory properties.

Coagulation abnormalities can occur in all types of infection, including both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial infections, or even in the absence of infection, such as in inflammatory states secondary to trauma or neurosurgery. Interestingly, they can also occur in patients with localized disease, such as those with respiratory infection. In a study by Günther et al., procoagulant activity in bronchial lavage fluid from patients with pneumonia or acute respiratory distress syndrome was found to be increased compared with that from control individuals, with a correlation between the severity of respiratory failure and level of coagulant activity.

Severe sepsis, defined as sepsis associated with acute organ dysfunction, results from a generalized inflammatory and procoagulant host response to infection. Once the endothelium becomes damaged, levels of endothelial thrombomodulin significantly decrease, and the body’s ability to convert Protein C to Activated Protein C diminishes. The ultimate cause of acute organ dysfunction in sepsis is injury to the vascular endothelium, which can result in microvascular coagulopathy.

(Vincent JL. Microvascular endothelial dysfunction: a renewed appreciation of sepsis pathophysiology.

Critical Care 2001; 5:S1–S5. http://ccforum.com/content/5/S2/S1)

Endothelial Cell Dysfunction in Severe Sepsis

During the past decade a unifying hypothesis has been developed to explain the vascular changes that occur in septic shock on the basis of the effect of inflammatory mediators on the vascular endothelium. The vascular endothelium plays a central role in the control of microvascular flow, and it has been proposed that widespread vascular endothelial activation, dysfunction and eventually injury occurs in septic shock, ultimately resulting in multiorgan failure. This has been characterized in various models of experimental septic shock. Now, direct and indirect evidence for endothelial cell alteration in humans during septic shock is emerging.

The vascular endothelium regulates the flow of nutrient substances, diverse biologically active molecules and the blood cells themselves. This role of endothelium is achieved through the presence of membrane-bound receptors for numerous molecules, including proteins, lipid transporting particles, metabolites and hormones, as well as through specific junction proteins and receptors that govern cell–cell and cell–matrix interactions. Endothelial dysfunction and/or injury with subendothelium exposure facilitates leucocyte and platelet aggregation, and aggravation of coagulopathy. Therefore, endothelial dysfunction and/or injury should favour impaired perfusion, tissue hypoxia and subsequent organ dysfunction.

Anatomical damage to the endothelium during septic shock has been assessed in several studies. A single injection of bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) has long been demonstrated to be a nonmechanical technique for removing endothelium. In endotoxic rabbits, observations tend to demonstrate that EC surface modification occurs easily and rapidly, with ECs being detached from the internal elastic lamina with an indication of subendothelial oedema. Proinflammatory cytokines increase permeability of the ECs, and this is manifested approximately 6 hours after inflammation is triggered and becomes maximal over 12–24 hours as the combination of cytokines exert potentiating effects. Endothelial physical disruption allows inflammatory fluid and cells to shift from the blood into the interstitial space.

In sepsis

- ECs become injured, prothrombotic and antifibrinolytic

- They promote platelet adhesion

- They promote leucocyte adhesion and inhibit vasodilation

An important point is that EC injury is sustained over time. In an endotoxic rabbit model, we demonstrated that endothelium denudation is present at the level of the abdominal aorta as early as after several hours following injury and persisted for at least 5 days afterward. After 21 days we observed that the endothelial surface had recovered. The de-endothelialized surface accounted for approximately 25% of the total surface.

Thrombomodulin and protein C activation at the microcirculatory level.

The endothelial cell surface thrombin (Th)-binding protein thrombomodulin (TM) is responsible for inhibition of thrombin activity. TM, when bound to Th, forms a potent protein C activator complex. Loss of TM and/or internalization results in Th–thrombin receptor (TR) interaction. Loss of TM and associated protein C activation represents the key event of decreased endothelial coagulation modulation ability and increased inflammation pathways.

( Iba T, Kidokoro A, Yagi Y: The role of the endothelium in changes in procoagulant activity in sepsis. J Am Coll Surg 1998; 187:321-329. Keywords: ATIII, antithrombin III; NF-κ, nuclear factor-κB; PAI,plasminogen activator inhibitor).

In order to test the role of the endothelial-derived relaxing factors NO and PGI2, we investigated, in dogs, the influence of a combination of NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (an inhibitor of NO synthesis) and indomethacin (an inhibitor of PGI2 synthesis). In these dogs treated with indomethacin plus NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester, the severity of the oxygen extraction defect was lower than that observed in the deoxycholate-treated dogs, suggesting that other mediators and/or mechanisms may be involved in microcirculatory control during hypoxia. One of these mediators or mechanisms could be related to hyperpolarization. Membrane potential is an important determinant of vascular smooth muscle tone through its influence on calcium influx via voltage-gated calcium channels. Hyperpolarization (as well as depolarization) has been shown to be a means of cell–cell communication in upstream vasodilatation and microcirculatory coordination. It is important to emphasize that intercell coupling exclusively involves ECs.

Interestingly, it was recently shown that sepsis, a situation that is characterized by impaired tissue perfusion and abnormal oxygen extraction, is associated with abnormal inter-EC coupling and reduction in the arteriolar conducted response. An intra-organ defect in blood flow related to abnormal vascular reactivity, cell adhesion and coagulopathy may account for impaired organ oxygen regulation and function. If specific classes of microvessels must or must not be perfused to achieve efficient oxygen extraction during limitation in oxygen delivery, then impaired vascular reactivity and vessel injury might produce a pathological limitation in supply. In sepsis, the inflammatory response profoundly alters circulatory homeostasis, and this has been referred to as a ‘malignant intravascular inflammation’ that alters vasomotor tone and the distribution of blood flow among and within organs. These mechanisms might coexist with other types of sepsis associated cell dysfunction. For example, data suggest that endotoxin directly impairs oxygen uptake in ECs and indicate the importance of endothelium respiration in maintaining vascular homeostasis under conditions of sepsis.

Consistent with the hypothesis that alteration in endothelium plays a major in the pathophysiology of sepsis, it was observed that chronic ecNOS overexpression in the endothelium of mice resulted in resistance to LPS-induced hypotension, lung injury and death . This observation was confirmed by another group of investigators, who used transgenic mice overexpressing adrenomedullin – a vasodilating peptide that acts at least in part via an NO-dependent pathway. They demonstrated resistance of these animals to LPS-induced shock, and lesser declines in blood pressure and less severe organ damage than occurred in the control animals. It might therefore be of importance to favour ecNOS expression and function during sepsis. The recent negative results obtained with therapeutic strategies aimed at blocking inducible NOS with the nonselective NOS inhibitor NG-monomethyl-L-arginine in human septic shock further confirm the overall importance of favoring vessel dilatation.

(Vallet B. Bench-to-bedside review: Endothelial cell dysfunction in severe sepsis: a role in organ dysfunction? Critical Care 2003; 7(2):130-138 (DOI 10.1186/cc1864). (Print ISSN 1364-8535; Online ISSN 1466-609X). http://ccforum.com/content/7/2/130

Thrombosis in Inflammatory Bowel Disease

An association between IBD and thrombosis has been recognized for more than 60 years. Not only are patients with IBD more likely to have thromboembolic complications, but it has also been suggested that thrombosis might be pathogenic in IBD.

Coagulation Described. See Part I. (Cascade)

Endothelial injury exposes TF, which forms a complex with factor VII. This complex activates factors X and, to a lesser extent, IX. TFPI prevents this activation progressing further; for coagulation to progress, factor Xa must be produced via factors IX and VIII. Thrombin, generated by the initial production of factor Xa, activates factor VIII and, through factor XI, factor IX, resulting in further activation of factor X. This positive feedback loop allows coagulation to proceed. Fibrin polymers are stabilized by factor XIIIa. Activated proteins CS (APCS) together inhibit factors VIIIa and Va, whereas antithrombin (AT) inhibits factors VIIa, IXa, Xa, and XIa. Fibrinolysis balances this system through the action of plasmin on fibrin. Plasminogen activator inhibitor controls the plasminogen activator-induced conversion of plasminogen to plasmin.

Inflammation and Thrombotic Processes Linked

Although interest has recently moved away from the proposal that ischemia is a primary cause of IBD, it has become increasingly clear that inflammatory and thrombotic processes are linked. A vascular component to the pathogenesis of CD was first proposed only a year after Crohn et al. described the condition. Subsequently, in 1989, a series of changes comprising vascular injury, focal arteritis, fibrin deposition, arterial occlusion, and then microinfarction or neovascularization was proposed as a possible pathogenetic sequence in CD. In this study, resin casts of the intestinal vasculature showed changes ranging from intravascular fibrin deposition to complete thrombotic occlusion. Furthermore, the early vascular changes appeared to precede mucosal changes, suggesting that they were more likely to cause rather than result from the pathologic features of CD. Subsequent studies showed that intravascular fibrin deposition occurred at the site of granulomatous destruction of mesenteric blood vessels, and positive immunostaining for platelet glycoprotein IIIa occurred in fibrinoid plugs of mucosal capillaries in CD. In addition, intracapillary thrombus has been identified in biopsies from inflamed rectal mucosa from patients with CD. When combined with evidence of ongoing intravascular coagulation in both active and quiescent CD, the above data point toward a thrombotic element contributing to the pathogenesis of CD.

Not only are many different prothrombotic changes described in association with IBD, but they can also have multiple causes. Hyperhomocysteinemia, for example, is known to predispose to thrombosis, and patients with IBD are more likely to have hyperhomocysteinemia than control subjects. Hyperhomocysteinemia in IBD might be due to multiple possible causes, such as deficiencies of vitamin B12 as a result of terminal ileal disease or resection; B6, which is commonly reduced in IBD. A vegan diet can’t be discarded either because of seriously deficient methyl donors (S-adenosyl methionine).

The realization that platelets are not only prothrombotic but also proinflammatory has stimulated interest in their role in both the pathogenesis and complications of IBD. The association between thrombocytosis and active IBD was first described more than 30 years ago. More recent observations link decreased or normal platelet survival to IBD-related thrombocytosis, possibly due to increased thrombopoiesis. This in turn could be driven by an interleukin-6 –induced increase in thrombopoietin synthesis in the liver. Spontaneous in vitro platelet aggregation occurs in platelets isolated from 30% of patients with IBD but not in platelets from control subjects. Moreover, collagen, arachidonic acid, ristocetin, and ADP-induced platelet activation are more marked in platelets from patients with active IBD than in those from healthy volunteers.

The roles of activated platelets and PLAs in mucosal inflammation. Activated platelets can interact with other cells involved in the inflammatory response either through direct contact or through the release of soluble mediators. Activated platelets interact directly with activated vascular endothelium, causing the latter to express adhesion molecules and release inflammatory and chemotactic cytokines.

Platelet activation might be pathogenic in IBD in several ways. Platelet activation might increase platelet aggregation, hence increasing the likelihood of thrombus formation at sites of vascular injury, for example, within the mesenteric circulation. P-selectin is the major ligand for leukocyte-endothelial interaction and is responsible for the rolling of platelets, leukocytes, and PLAs on vascular endothelium. Moreover, platelets adherent to injured vascular endothelium support leukocyte adhesion via P-selectin, an effect that could contribute to leukocyte emigration from the vasculature into the lamina propria in patients with IBD. In addition, P-selectin is the major platelet ligand for platelet-leukocyte interaction, which in turn causes both leukocyte activation and further platelet activation.

Platelet-Leukocyte Aggregation

Recently, studies showing that platelets and leukocytes that circulate together in aggregates (PLA) are more activated than those that circulate alone have generated interest in the role of PLA in various inflammatory and thrombotic conditions. PLA numbers are increased in patients with ischemic heart disease, systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis, myeloproliferative disorders, and sepsis and are increased by smoking.

We have recently shown that patients with IBD have more PLAs than both healthy and inflammatory control subjects (patients with inflammatory arthritides). As with platelet activation, there was no correlation with disease activity, suggesting that increased PLA formation might be an underlying abnormality. PLAs could contribute to the pathogenesis of IBD in a number of ways. As previously mentioned, TF is key to the initiation of thrombus formation. TF has recently been demonstrated on the surface of activated platelets and in platelet-derived microvesicles. Interaction between neutrophils and activated platelets or microvesicles vastly increases the activity of “intravascular” TF.

Conclusion

It is becoming increasingly apparent that thrombosis and inflammation are intrinsically linked. Hence the involvement of thrombotic processes in the pathogenesis of IBD, although perhaps not as the primary event, seems likely. Indeed, with the recently mounting evidence of the role of activated platelets and of their interaction with leukocytes in the pathogenesis of IBD, it seems even more probable that thrombosis plays some role in the pathogenic process.

(Irving PM, Pasi KJ, and Rampton DS. Thrombosis and Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2005;3:617–628. PII: 10.1053/S1542-3565(05)00154-0.)

Bleeding in Patients with Renal Insufficiency

Approximately 20–40% of critically ill patients will have renal insufficiency at the time of admission or will develop it during their ICU stay, depending on the definition of renal insufficiency and the case mix of the ICU. Such patients are also predisposed to bleeding because of uremic platelet dysfunction, typically multiple comorbidities, coagulopathies and frequent concomitant treatment with antiplatelet or anticoagulant agents.

The impairment in hemostasis in uremic patients is multifactorial and includes physiological defects in platelet hemostasis, an imbalance of mediators of normal endothelial function and frequent comorbidities such as vascular disease, anemia and the frequent need for medical interventions required to treat such comorbidities. Physiologic alterations in uremia include:

- decreased platelet glycoprotein IIb–IIIa binding to both von Willebrand factor (vWf) and fibrinogen, causing an impairment in platelet aggregation;

- increased prostacyclin and nitric oxide production, both potent inhibitors of platelet activation and vasoconstriction; and

- decreased levels of platelet adenosine diphosphate (ADP) and serotonin, causing an impairment in platelet secretion.

In addition to other factors, small peptides containing the RGD (Arg-Gly-Asp) sequence of amino acids have been shown to be inhibitors of platelet aggregation that act by competing with vWf and fibrinogen for binding to the glycoprotein IIb–IIIa receptor.

Conclusion

ICU patients have dynamic risks of thrombosis and bleeding. Invasive procedures may require temporary interruption of anticoagulants. Consequently, approaches to thromboprophylaxis require daily reevaluation.

(Cook DJ, Douketis J, Arnold D, and Crowther MA. Bleeding and venous thromboembolism in the critically ill with emphasis on patients with renal insufficiency. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2009;15:455–462.)

Epicrisis

I have covered a large amount of material on one of the most complex systems in medicine, and still not comprehensive, with a sufficient dash of repetition. The task is to have some grasp of the cell-mediated imbalances inherent if coagulation and bleeding disorders. The key points are:

- inflammation and oxidative stress invariably lurk in the background

- the Y-shaped model with an extrinsic, intrinsic, and common pathway has no basis in understanding

- the current model is based on a cell-mediated concept of endothelial damage and platelet-endothelial interaction

- the model has 3 components: Initiation, Amplification, Propagation

- NO and prostacyclin have key roles in the process

- The plasma proteins involved are in the serine-protease class of enzymes

- The conversion of Protein C to APC has a central role as anti-coagulant

Part II has explored organ system abnormalities that are all related to impairment of the Nitric Oxide balance and dual platelet-endothelial roles.

- interaction of Nitric Oxide and Prostacyclin in Vascular Endothelium (pharmaceuticalintelligence.com)

- Nitric oxide: role in Cardiovascular health and disease (pharmaceuticalintelligence.com)

- Nitric Oxide has a ubiquitous role in the regulation of glycolysis -with a concomitant influence on mitochondrial function (pharmaceuticalintelligence.com)

- Differential Distribution of Nitric Oxide – A 3-D Mathematical Model (pharmaceuticalintelligence.com)

- Nitric Oxide and Sepsis, Hemodynamic Collapse, and the Search for Therapeutic Options (pharmaceuticalintelligence.com)

- Potentiation of Thrombin Generation in Hemophilia A Plasma by Coagulation Factor VIII and Characterization of Antibody-Specific Inhibition (plosone.org)

- Nitric Oxide Covalent Modifications: A Putative Therapeutic Target? (pharmaceuticalintelligence.com)

- Nitric Oxide and Immune responses: part 1 (pharmaceuticalintelligence.com)

- Nitric Oxide and Immune Responses: Part 2 (pharmaceuticalintelligence.com)

- Statins’ nonlipid effects on vascular endothelium through eNOS activation (pharmaceuticalintelligence.com)

Computational models are very efficient tools to understand complex reactions like NO towards physiological conditions. Among them wall shear stress is one of the major factors which is reviewed in the article – “Differential Distribution of Nitric Oxide – A 3-D Mathematical Model”.

Moreover, decrease in availability of NO can lead to many complications like pulmonary hypertension. Some of the causes of decrease in NO have been identified as clinical hypertension,right ventricular overload which can lead to cardiac heart failure,low levels of zinc and high levels of cardiac necrosis.

Sickle Cell disease patients, a hereditary disease, are also known to have decreased levels of NO which can become physiologically challenging. In USA alone, there are 90,000 people who are affected by Sickle cell disease.

Sickle cell disease is breakage of red blood cells (RBC) membrane and resulting release of the hemoglobin (Hb) into blood plasma. This process is also known as Hemolysis. Sickle cell disease is caused by single mutation of Hb which changes RBC from round shape to sickle or crescent shapes (Figure 1).

Figure 1 (B) shows abnormal, sickled red blood cells The inset image shows a cross-section of a sickle cell with long polymerized HbS strands stretching and distorting the cell shape.

Image Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sickle-cell_disease

RBCs generally breakdown and release Hbs in blood plasma after they reach their end of life span. Thus, in case of Sickle cell disease, there is more cell free Hb than normal. Furthermore, it is known that NO has a very high affinity towards Hbs, which is one of the ways free NO is regulated in blood. As a result presence of larger amounts of cell free Hb in Sickle cell disease lead to less availability of NO.

As to “a quantitative relationship between cell free Hb and depletion of NO”, Deonikar and Kavdia (J. Appl. Physiol., 2012) addressed this question by developing a model of a single idealized arteriole, with different layers of blood vessels diffusing nutrients to tissue layers (Figure 2: Deonikar and Kavdia Figure 1).

The model and its parameters are explained in the previously published paper by same authors Deonikar and Kavdia, Annals of Biomed., 2010, who reported that the reaction rate between NO and RBC is 0.2 x 105, M-1 s-1 than 1.4 x 105, M-1 s-1 as previously reported by Butler et.al., Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1998. Their results show that even small increase in cell free Hb, 0.5uM, can decrease NO concentrations by 3-7 fold. Their mathematical analysis shows that the increase in diffusion resistance of NO from vascular lumen to cell free zone has no effect on NO distribution and concentration with available levels of cell free Hb.

Deonikar and Kavdia’s model, a simple representation shows that for SC disease patients, decrease in levels of bioavailable NO is attributed to cell free Hb, which is in abundant for these patients. Their results show that small increase by 0.5 uM in cell free Hb can cause a large decrease in NO concentrations.

Sources:

Deonikar and Kavdia (2012):http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22223452

Previous model explaining mathematical representation and parameters used in the model :Deonikar and Kavdia,Annals of Biomed., 2010.

Previous paper stating reaction rate of Hb and NO: Butleret.al., Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1998.

Causes of decrease in NO

Clinical Hypertension :http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11311074

Right ventricular overload :http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9559613

Low levels of zinc and high levels of cardiac necrosis :http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11243421

Sickle Cell Source:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sickle-cell_disease

http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/sca/

NO Sources:

Differential Distribution of Nitric Oxide – A 3-D Mathematical Model:

Discovery of NO and its effects of vascular biology

Nitric oxide: role in Cardiovascular health and disease

The rationale and use of inhaled NO in Pulmonary Artery Hypertension and Right Sided Heart Failure

Endothelial Function and Cardiovascular Disease

Interaction of Nitric Oxide and Prostacyclin in Vascular Endothelium

Endothelial Dysfunction, Diminished Availability of cEPCs, Increasing CVD Risk – Macrovascular Disease – Therapeutic Potential of cEPCs