Summary of Translational Medicine – e-Series A: Cardiovascular Diseases, Volume Four – Part 1

Author and Curator: Larry H Bernstein, MD, FCAP

and

Curator: Aviva Lev-Ari, PhD, RN

Article ID #135: Summary of Translational Medicine – e-Series A: Cardiovascular Diseases, Volume Four – Part 1. Published on 4/28/2014

WordCloud Image Produced by Adam Tubman

Part 1 of Volume 4 in the e-series A: Cardiovascular Diseases and Translational Medicine, provides a foundation for grasping a rapidly developing surging scientific endeavor that is transcending laboratory hypothesis testing and providing guidelines to:

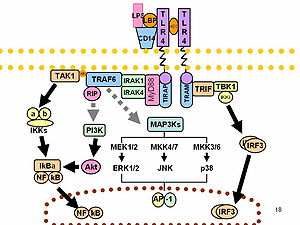

- Target genomes and multiple nucleotide sequences involved in either coding or in regulation that might have an impact on complex diseases, not necessarily genetic in nature.

- Target signaling pathways that are demonstrably maladjusted, activated or suppressed in many common and complex diseases, or in their progression.

- Enable a reduction in failure due to toxicities in the later stages of clinical drug trials as a result of this science-based understanding.

- Enable a reduction in complications from the improvement of machanical devices that have already had an impact on the practice of interventional procedures in cardiology, cardiac surgery, and radiological imaging, as well as improving laboratory diagnostics at the molecular level.

- Enable the discovery of new drugs in the continuing emergence of drug resistance.

- Enable the construction of critical pathways and better guidelines for patient management based on population outcomes data, that will be critically dependent on computational methods and large data-bases.

What has been presented can be essentially viewed in the following Table:

There are some developments that deserve additional development:

1. The importance of mitochondrial function in the activity state of the mitochondria in cellular work (combustion) is understood, and impairments of function are identified in diseases of muscle, cardiac contraction, nerve conduction, ion transport, water balance, and the cytoskeleton – beyond the disordered metabolism in cancer. A more detailed explanation of the energetics that was elucidated based on the electron transport chain might also be in order.

2. The processes that are enabling a more full application of technology to a host of problems in the environment we live in and in disease modification is growing rapidly, and will change the face of medicine and its allied health sciences.

Electron Transport and Bioenergetics

Deferred for metabolomics topic

Synthetic Biology

Introduction to Synthetic Biology and Metabolic Engineering

Kristala L. J. Prather: Part-1 <iBiology > iBioSeminars > Biophysics & Chemical Biology >

http://www.ibiology.org Lecturers generously donate their time to prepare these lectures. The project is funded by NSF and NIGMS, and is supported by the ASCB and HHMI.

Dr. Prather explains that synthetic biology involves applying engineering principles to biological systems to build “biological machines”.

| Prather 1: Synthetic Biology and Metabolic Engineering 2/6/14IntroductionLecture Overview In the first part of her lecture, Dr. Prather explains that synthetic biology involves applying engineering principles to biological systems to build “biological machines”. The key material in building these machines is synthetic DNA. Synthetic DNA can be added in different combinations to biological hosts, such as bacteria, turning them into chemical factories that can produce small molecules of choice. In Part 2, Prather describes how her lab used design principles to engineer E. coli that produce glucaric acid from glucose. Glucaric acid is not naturally produced in bacteria, so Prather and her colleagues “bioprospected” enzymes from other organisms and expressed them in E. coli to build the needed enzymatic pathway. Prather walks us through the many steps of optimizing the timing, localization and levels of enzyme expression to produce the greatest yield. Speaker Bio: Kristala Jones Prather received her S.B. degree from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and her PhD at the University of California, Berkeley both in chemical engineering. Upon graduation, Prather joined the Merck Research Labs for 4 years before returning to academia. Prather is now an Associate Professor of Chemical Engineering at MIT and an investigator with the multi-university Synthetic Biology Engineering Reseach Center (SynBERC). Her lab designs and constructs novel synthetic pathways in microorganisms converting them into tiny factories for the production of small molecules. Dr. Prather has received numerous awards both for her innovative research and for excellence in teaching. |

VIEW VIDEOS

https://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=ndThuqVumAk#t=0

https://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=ndThuqVumAk#t=12

https://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=ndThuqVumAk#t=74

https://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=ndThuqVumAk#t=129

https://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=ndThuqVumAk#t=168

https://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=ndThuqVumAk

David Bartel: micro-RNAs

I. Introduction to microRNAs

https://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=dupzE66J8u4#t=0

– See more at: http://www.ibiology.org/ibioseminars/genetics-gene-regulation/david-bartel-part-1.html#sthash.nGGr1tIt.dpuf

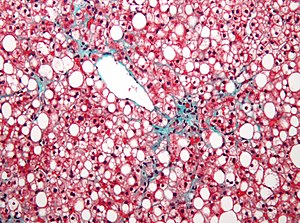

Calcium Cycling in Synthetic and Contractile Phasic or Tonic Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells

Current Basic and Pathological Approaches to

the Function of Muscle Cells and Tissues – From Molecules to HumansLarissa Lipskaia, Isabelle Limon, Regis Bobe and Roger Hajjar

Additional information is available at the end of the chapter

http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/48240

Calcium ions (Ca ) are present in low concentrations in the cytosol (~100 nM) and in high concentrations (in mM range) in both the extracellular medium and intracellular stores (mainly sarco/endo/plasmic reticulum, SR). This differential allows the calcium ion messenger that carries information

as diverse as contraction, metabolism, apoptosis, proliferation and/or hypertrophic growth. The mechanisms responsible for generating a Ca signal greatly differ from one cell type to another.

For instance, in contractile VSMCs, the initiation of contractile events is driven by mem- brane depolarization; and the principal entry-point for extracellular Ca is the voltage-operated L-type calcium channel (LTCC). In contrast, in synthetic/proliferating VSMCs, the principal way-in for extracellular Ca is the store-operated calcium (SOC) channel.

Whatever the cell type, the calcium signal consists of limited elevations of cytosolic free calcium ions in time and space. The calcium pump, sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca ATPase (SERCA), has a critical role in determining the frequency of SR Ca release by upload into the sarcoplasmic

sensitivity of SR calcium channels, Ryanodin Receptor, RyR and Inositol tri-Phosphate Receptor, IP3R.

Synthetic VSMCs have a fibroblast appearance, proliferate readily, and synthesize increased levels of various extracellular matrix components, particularly fibronectin, collagen types I and III, and tropoelastin [1].

Contractile VSMCs have a muscle-like or spindle-shaped appearance and well-developed contractile apparatus resulting from the expression and intracellular accumulation of thick and thin muscle filaments [1].

Figure 1. Schematic representation of Calcium Cycling in Contractile and Proliferating VSMCs.

Left panel: schematic representation of calcium cycling in quiescent /contractile VSMCs. Contractile re-sponse is initiated by extracellular Ca influx due to activation of Receptor Operated Ca (through phosphoinositol-coupled receptor) or to activation of L-Type Calcium channels (through an increase in luminal pressure). Small increase of cytosolic due IP3 binding to IP3R (puff) or RyR activation by LTCC or ROC-dependent Ca influx leads to large SR Ca IP3R or RyR clusters (“Ca -induced Ca SR calcium pumps (both SERCA2a and SERCA2b are expressed in quiescent VSMCs), maintaining high concentration of cytosolic Ca and setting the sensitivity of RyR or IP3R for the next spike.

Contraction of VSMCs occurs during oscillatory Ca transient.

Middle panel: schematic representa tion of atherosclerotic vessel wall. Contractile VSMC are located in the media layer, synthetic VSMC are located in sub-endothelial intima.

Right panel: schematic representation of calcium cycling in quiescent /contractile VSMCs. Agonist binding to phosphoinositol-coupled receptor leads to the activation of IP3R resulting in large increase in cytosolic Ca calcium pumps (only SERCA2b, having low turnover and low affinity to Ca depletion leads to translocation of SR Ca sensor STIM1 towards PM, resulting in extracellular Ca influx though opening of Store Operated Channel (CRAC). Resulted steady state Ca transient is critical for activation of proliferation-related transcription factors ‘NFAT).

Abbreviations: PLC – phospholipase C; PM – plasma membrane; PP2B – Ca /calmodulin-activated protein phosphatase 2B (calcineurin); ROC- receptor activated channel; IP3 – inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate, IP3R – inositol-1,4,5- trisphosphate receptor; RyR – ryanodine receptor; NFAT – nuclear factor of activated T-lymphocytes; VSMC – vascular smooth muscle cells; SERCA – sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca sarcoplasmic reticulum.

Time for New DNA Synthesis and Sequencing Cost Curves

By Rob Carlson

I’ll start with the productivity plot, as this one isn’t new. For a discussion of the substantial performance increase in sequencing compared to Moore’s Law, as well as the difficulty of finding this data, please see this post. If nothing else, keep two features of the plot in mind: 1) the consistency of the pace of Moore’s Law and 2) the inconsistency and pace of sequencing productivity. Illumina appears to be the primary driver, and beneficiary, of improvements in productivity at the moment, especially if you are looking at share prices. It looks like the recently announced NextSeq and Hiseq instruments will provide substantially higher productivities (hand waving, I would say the next datum will come in another order of magnitude higher), but I think I need a bit more data before officially putting another point on the plot.

Illumina’s instruments are now responsible for such a high percentage of sequencing output that the company is effectively setting prices for the entire industry. Illumina is being pushed by competition to increase performance, but this does not necessarily translate into lower prices. It doesn’t behoove Illumina to drop prices at this point, and we won’t see any substantial decrease until a serious competitor shows up and starts threatening Illumina’s market share. The absence of real competition is the primary reason sequencing prices have flattened out over the last couple of data points.

Note that the oligo prices above are for column-based synthesis, and that oligos synthesized on arrays are much less expensive. However, array synthesis comes with the usual caveat that the quality is generally lower, unless you are getting your DNA from Agilent, which probably means you are getting your dsDNA from Gen9.

Note also that the distinction between the price of oligos and the price of double-stranded sDNA is becoming less useful. Whether you are ordering from Life/Thermo or from your local academic facility, the cost of producing oligos is now, in most cases, independent of their length. That’s because the cost of capital (including rent, insurance, labor, etc) is now more significant than the cost of goods. Consequently, the price reflects the cost of capital rather than the cost of goods. Moreover, the cost of the columns, reagents, and shipping tubes is certainly more than the cost of the atoms in the sDNA you are ostensibly paying for. Once you get into longer oligos (substantially larger than 50-mers) this relationship breaks down and the sDNA is more expensive. But, at this point in time, most people aren’t going to use longer oligos to assemble genes unless they have a tricky job that doesn’t work using short oligos.

Looking forward, I suspect oligos aren’t going to get much cheaper unless someone sorts out how to either 1) replace the requisite human labor and thereby reduce the cost of capital, or 2) finally replace the phosphoramidite chemistry that the industry relies upon.

IDT’s gBlocks come at prices that are constant across quite substantial ranges in length. Moreover, part of the decrease in price for these products is embedded in the fact that you are buying smaller chunks of DNA that you then must assemble and integrate into your organism of choice.

Someone who has purchased and assembled an absolutely enormous amount of sDNA over the last decade, suggested that if prices fell by another order of magnitude, he could switch completely to outsourced assembly. This is a potentially interesting “tipping point”. However, what this person really needs is sDNA integrated in a particular way into a particular genome operating in a particular host. The integration and testing of the new genome in the host organism is where most of the cost is. Given the wide variety of emerging applications, and the growing array of hosts/chassis, it isn’t clear that any given technology or firm will be able to provide arbitrary synthetic sequences incorporated into arbitrary hosts.

TrackBack URL: http://www.synthesis.cc/cgi-bin/mt/mt-t.cgi/397

Startup to Strengthen Synthetic Biology and Regenerative Medicine Industries with Cutting Edge Cell Products

28 Nov 2013 | PR Web

Dr. Jon Rowley and Dr. Uplaksh Kumar, Co-Founders of RoosterBio, Inc., a newly formed biotech startup located in Frederick, are paving the way for even more innovation in the rapidly growing fields of Synthetic Biology and Regenerative Medicine. Synthetic Biology combines engineering principles with basic science to build biological products, including regenerative medicines and cellular therapies. Regenerative medicine is a broad definition for innovative medical therapies that will enable the body to repair, replace, restore and regenerate damaged or diseased cells, tissues and organs. Regenerative therapies that are in clinical trials today may enable repair of damaged heart muscle following heart attack, replacement of skin for burn victims, restoration of movement after spinal cord injury, regeneration of pancreatic tissue for insulin production in diabetics and provide new treatments for Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases, to name just a few applications.

While the potential of the field is promising, the pace of development has been slow. One main reason for this is that the living cells required for these therapies are cost-prohibitive and not supplied at volumes that support many research and product development efforts. RoosterBio will manufacture large quantities of standardized primary cells at high quality and low cost, which will quicken the pace of scientific discovery and translation to the clinic. “Our goal is to accelerate the development of products that incorporate living cells by providing abundant, affordable and high quality materials to researchers that are developing and commercializing these regenerative technologies” says Dr. Rowley

Life at the Speed of Light

http://kcpw.org/?powerpress_pinw=92027-podcast

NHMU Lecture featuring – J. Craig Venter, Ph.D.

Founder, Chairman, and CEO – J. Craig Venter Institute; Co-Founder and CEO, Synthetic Genomics Inc.

J. Craig Venter, Ph.D., is Founder, Chairman, and CEO of the J. Craig Venter Institute (JVCI), a not-for-profit, research organization dedicated to human, microbial, plant, synthetic and environmental research. He is also Co-Founder and CEO of Synthetic Genomics Inc. (SGI), a privately-held company dedicated to commercializing genomic-driven solutions to address global needs.

In 1998, Dr. Venter founded Celera Genomics to sequence the human genome using new tools and techniques he and his team developed. This research culminated with the February 2001 publication of the human genome in the journal, Science. Dr. Venter and his team at JVCI continue to blaze new trails in genomics. They have sequenced and a created a bacterial cell constructed with synthetic DNA, putting humankind at the threshold of a new phase of biological research. Whereas, we could previously read the genetic code (sequencing genomes), we can now write the genetic code for designing new species.

The science of synthetic genomics will have a profound impact on society, including new methods for chemical and energy production, human health and medical advances, clean water, and new food and nutritional products. One of the most prolific scientists of the 21st century for his numerous pioneering advances in genomics, he guides us through this emerging field, detailing its origins, current challenges, and the potential positive advances.

His work on synthetic biology truly embodies the theme of “pushing the boundaries of life.” Essentially, Venter is seeking to “write the software of life” to create microbes designed by humans rather than only through evolution. The potential benefits and risks of this new technology are enormous. It also requires us to examine, both scientifically and philosophically, the question of “What is life?”

J Craig Venter wants to digitize DNA and transmit the signal to teleport organisms

2013 Genomics: The Era Beyond the Sequencing of the Human Genome: Francis Collins, Craig Venter, Eric Lander, et al.

Human Longevity Inc (HLI) – $70M in Financing of Venter’s New Integrative Omics and Clinical Bioinformatics

Where Will the Century of Biology Lead Us?

By Randall Mayes

A technology trend analyst offers an overview of synthetic biology, its potential applications, obstacles to its development, and prospects for public approval.

- In addition to boosting the economy, synthetic biology projects currently in development could have profound implications for the future of manufacturing, sustainability, and medicine.

- Before society can fully reap the benefits of synthetic biology, however, the field requires development and faces a series of hurdles in the process. Do researchers have the scientific know-how and technical capabilities to develop the field?

Biology + Engineering = Synthetic Biology

Bioengineers aim to build synthetic biological systems using compatible standardized parts that behave predictably. Bioengineers synthesize DNA parts—oligonucleotides composed of 50–100 base pairs—which make specialized components that ultimately make a biological system. As biology becomes a true engineering discipline, bioengineers will create genomes using mass-produced modular units similar to the microelectronics and computer industries.

Currently, bioengineering projects cost millions of dollars and take years to develop products. For synthetic biology to become a Schumpeterian revolution, smaller companies will need to be able to afford to use bioengineering concepts for industrial applications. This will require standardized and automated processes.

A major challenge to developing synthetic biology is the complexity of biological systems. When bioengineers assemble synthetic parts, they must prevent cross talk between signals in other biological pathways. Until researchers better understand these undesired interactions that nature has already worked out, applications such as gene therapy will have unwanted side effects. Scientists do not fully understand the effects of environmental and developmental interaction on gene expression. Currently, bioengineers must repeatedly use trial and error to create predictable systems.

Similar to physics, synthetic biology requires the ability to model systems and quantify relationships between variables in biological systems at the molecular level.

The second major challenge to ensuring the success of synthetic biology is the development of enabling technologies. With genomes having billions of nucleotides, this requires fast, powerful, and cost-efficient computers. Moore’s law, named for Intel co-founder Gordon Moore, posits that computing power progresses at a predictable rate and that the number of components in integrated circuits doubles each year until its limits are reached. Since Moore’s prediction, computer power has increased at an exponential rate while pricing has declined.

DNA sequencers and synthesizers are necessary to identify genes and make synthetic DNA sequences. Bioengineer Robert Carlson calculated that the capabilities of DNA sequencers and synthesizers have followed a pattern similar to computing. This pattern, referred to as the Carlson Curve, projects that scientists are approaching the ability to sequence a human genome for $1,000, perhaps in 2020. Carlson calculated that the costs of reading and writing new genes and genomes are falling by a factor of two every 18–24 months. (see recent Carlson comment on requirement to read and write for a variety of limiting conditions).

Startup to Strengthen Synthetic Biology and Regenerative Medicine Industries with Cutting Edge Cell Products

Synthetic Biology: On Advanced Genome Interpretation for Gene Variants and Pathways: What is the Genetic Base of Atherosclerosis and Loss of Arterial Elasticity with Aging

Synthesizing Synthetic Biology: PLOS Collections

http://pharmaceuticalintelligence.com/2012/08/17/synthesizing-synthetic-biology-plos-collections/

Capturing ten-color ultrasharp images of synthetic DNA structures resembling numerals 0 to 9

Silencing Cancers with Synthetic siRNAs

http://pharmaceuticalintelligence.com/2013/12/09/silencing-cancers-with-synthetic-sirnas/

Genomics Now—and Beyond the Bubble

Futurists have touted the twenty-first century as the century of biology based primarily on the promise of genomics. Medical researchers aim to use variations within genes as biomarkers for diseases, personalized treatments, and drug responses. Currently, we are experiencing a genomics bubble, but with advances in understanding biological complexity and the development of enabling technologies, synthetic biology is reviving optimism in many fields, particularly medicine.

BY MICHAEL BROOKS 17 APR, 2014 http://www.newstatesman.com/

Michael Brooks holds a PhD in quantum physics. He writes a weekly science column for the New Statesman, and his most recent book is The Secret Anarchy of Science.

The basic idea is that we take an organism – a bacterium, say – and re-engineer its genome so that it does something different. You might, for instance, make it ingest carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, process it and excrete crude oil.

That project is still under construction, but others, such as using synthesised DNA for data storage, have already been achieved. As evolution has proved, DNA is an extraordinarily stable medium that can preserve information for millions of years. In 2012, the Harvard geneticist George Church proved its potential by taking a book he had written, encoding it in a synthesised strand of DNA, and then making DNA sequencing machines read it back to him.

When we first started achieving such things it was costly and time-consuming and demanded extraordinary resources, such as those available to the millionaire biologist Craig Venter. Venter’s team spent most of the past two decades and tens of millions of dollars creating the first artificial organism, nicknamed “Synthia”. Using computer programs and robots that process the necessary chemicals, the team rebuilt the genome of the bacterium Mycoplasma mycoides from scratch. They also inserted a few watermarks and puzzles into the DNA sequence, partly as an identifying measure for safety’s sake, but mostly as a publicity stunt.

What they didn’t do was redesign the genome to do anything interesting. When the synthetic genome was inserted into an eviscerated bacterial cell, the new organism behaved exactly the same as its natural counterpart. Nevertheless, that Synthia, as Venter put it at the press conference to announce the research in 2010, was “the first self-replicating species we’ve had on the planet whose parent is a computer” made it a standout achievement.

Today, however, we have entered another era in synthetic biology and Venter faces stiff competition. The Steve Jobs to Venter’s Bill Gates is Jef Boeke, who researches yeast genetics at New York University.

Boeke wanted to redesign the yeast genome so that he could strip out various parts to see what they did. Because it took a private company a year to complete just a small part of the task, at a cost of $50,000, he realised he should go open-source. By teaching an undergraduate course on how to build a genome and teaming up with institutions all over the world, he has assembled a skilled workforce that, tinkering together, has made a synthetic chromosome for baker’s yeast.

Stepping into DIYbio and Synthetic Biology at ScienceHack

Posted April 22, 2014 by Heather McGaw and Kyrie Vala-Webb

We got a crash course on genetics and protein pathways, and then set out to design and build our own pathways using both the “Genomikon: Violacein Factory” kit and Synbiota platform. With Synbiota’s software, we dragged and dropped the enzymes to create the sequence that we were then going to build out. After a process of sketching ideas, mocking up pathways, and writing hypotheses, we were ready to start building!

The night stretched long, and at midnight we were forced to vacate the school. Not quite finished, we loaded our delicate bacteria, incubator, and boxes of gloves onto the bus and headed back to complete our bacterial transformation in one of our hotel rooms. Jammed in between the beds and the mini-fridge, we heat-shocked our bacteria in the hotel ice bucket. It was a surreal moment.

While waiting for our bacteria, we held an “unconference” where we explored bioethics, security and risk related to synthetic biology, 3D printing on Mars, patterns in juggling (with live demonstration!), and even did a Google Hangout with Rob Carlson. Every few hours, we would excitedly check in on our bacteria, looking for bacterial colonies and the purple hue characteristic of violacein.

Most impressive was the wildly successful and seamless integration of a diverse set of people: in a matter of hours, we were transformed from individual experts and practitioners in assorted fields into cohesive and passionate teams of DIY biologists and science hackers. The ability of everyone to connect and learn was a powerful experience, and over the course of just one weekend we were able to challenge each other and grow.

Returning to work on Monday, we were hungry for more. We wanted to find a way to bring the excitement and energy from the weekend into the studio and into the projects we’re working on. It struck us that there are strong parallels between design and DIYbio, and we knew there was an opportunity to bring some of the scientific approaches and curiosity into our studio.