Posts Tagged ‘Nitric oxide synthase’

Protected: Flywheel iNO, Three Novel Adult Patient Inhaled Nitric Oxide Product Concepts by Justin D. Pearlman MD ME PhD FACC

Posted in Medical Devices R&D Investment, Medical Imaging Technology, Image Processing/Computing, MRI, CT, Nuclear Medicine, Ultra Sound, Nitric Oxide in Health and Disease, Technology Transfer: Biotech and Pharmaceutical, tagged Heart Failure, Hypertension, nitric oxide, Nitric oxide synthase, Pulmonary hypertension, Torr on June 3, 2013|

Telling NO to Cardiac Risk

Posted in Bio Instrumentation in Experimental Life Sciences Research, Biological Networks, Gene Regulation and Evolution, Biomarkers & Medical Diagnostics, Cardiac & Vascular Repair Tools Subsegment, Cardiovascular Pharmacogenomics, Cell Biology, Signaling & Cell Circuits, Cerebrovascular and Neurodegenerative Diseases, Chemical Biology and its relations to Metabolic Disease, Chemical Genetics, Disease Biology, Small Molecules in Development of Therapeutic Drugs, Frontiers in Cardiology and Cardiovascular Disorders, Genome Biology, Health Economics and Outcomes Research, HTN, Molecular Genetics & Pharmaceutical, Nitric Oxide in Health and Disease, Origins of Cardiovascular Disease, Personalized and Precision Medicine & Genomic Research, Pharmaceutical R&D Investment, Pharmacotherapy of Cardiovascular Disease, Population Health Management, Genetics & Pharmaceutical, Regulated Clinical Trials: Design, Methods, Components and IRB related issues, Technology Transfer: Biotech and Pharmaceutical, tagged ADMA, Asymmetric dimethylarginine, Aviva Lev-Ari, Biology, Cardiovascular disease, Cardiovascular Disorders, Cell Biology, Conditions and Diseases, DDAH, Endothelium, health, Heart disease, medicine, nitric oxide, Nitric oxide synthase, NO, PubChem, research, ROS, science, Vascular smooth muscle on December 10, 2012| 9 Comments »

Telling NO to Cardiac Risk

DDAH Says NO to ADMA(1); The DDAH/ADMA/NOS Pathway(2)

Author-Writer-Reporter: Stephen J. Williams, PhD

Endothelium-derived nitric oxide (NO) has been shown to be vasoprotective. Nitric oxide enhances endothelial cell survival, inhibits excessive proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells, regulates vascular smooth muscle tone, and prevents platelets from sticking to the endothelial wall. Together with evidence from preclinical and human studies, it is clear that impairment of the NOS pathway increases risk of cardiovascular disease (3-5).

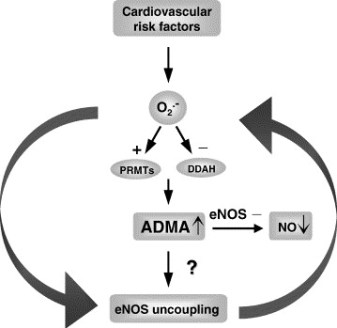

This post contains two articles on the physiological regulation of nitric oxide (NO) by an endogenous NO synthase inhibitor asymmetrical dimethylarginine (ADMA) and ADMA metabolism by the enzyme DDAH(1,2). Previous posts on nitric oxide, referenced at the bottom of the page, provides excellent background and further insight for this posting. In summary plasma ADMA levels are elevated in patients with cardiovascular disease and several large studies have shown that plasma ADMA is an independent biomarker for cardiovascular-related morbidity and mortality(6-8).

Figure 1 A. Cardiac risks of ADMA B. Effects of ADMA (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

ADMA Production and Metabolism

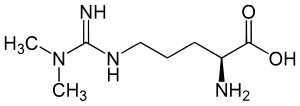

Nuclear proteins such as histones can be methylated on arginine residues by protein-arginine methyltransferases, enzymes which use S-adenosylmethionine as methyl groups. This methylation event is thought to regulate protein function, much in the way of protein acetylation and phosphorylation (9). And much like phosphorylation, these modifications are reversible through methylesterases. The proteolysis of these arginine-methyl modifications lead to the liberation of free guanidine-methylated arginine residues such as L-NMMA, asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) and symmetrical methylarginine (SDMA).

The first two, L-NMMA and ADMA, have been shown to inhibit the activity of the endothelial NOS. This protein turnover is substantial: for instance the authors note that each day 40% of constitutive protein in adult liver is newly synthesized protein. And in several diseases, such as muscular dystrophy, ischemic heart disease, and diabetes, it has been known since the 1970’s that protein catabolism rates are very high, with corresponding increased urinary excretion of ADMA(10-13). Methylarginines are excreted in the urine by cationic transport. However, the majority of ADMA and L-NMMA are degraded within the cell by dimethylaminohydrolase (DDAH), first cloned and purified in rat(14).

Figure 2. Endogenous inhibitors of NO synthase. Chemical structures generated from PubChem.

DDAH

DDAH specifically hydrolyzes ADMA and L-NMMA to yield citruline and demethylamine and usually shows co-localization with NOS. Pharmacologic inhibition of DDAH activity causes accumulation of ADMA and can reverse the NO-mediated bradykinin-induced relaxation of human saphenous vein.

Two isoforms have been found in human:

- DDAH1 (found in brain and kidney and associated with nNOS) and

- DDAH2 (highly expressed in heart, placenta, and kidney and associated with eNOS).

DDAH2 can be upregulated by all-trans retinoic acid (atRA can increase NO production). Increased reactive oxygen species and possibly homocysteine, a risk factor for cardiovascular disease, can decrease DDAH activity(15,16).

- The importance of DDAH activity can also be seen in transgenic mice which overexpress DDAH, exhibiting increased NO production, increased insulin sensitivity, and reduced vascular resistance (17). Likewise,

- Transgenic mice, null for the DDAH1, showed increase in blood pressure, decreased NO production, and significant increase in tissue and plasma ADMA and L-NMMA.

Figure 3. The DDAH/ADMA/NOS cycle. Figure adapted from Cooke and Ghebremarian (1).

As mentioned in the article by Cooke and Ghebremariam, the authors state: the weight of the evidence indicates that DDAH is a worthy therapeutic target. Agents that increase DDAH expression are known, and 1 of these, a farnesoid X receptor agonist, is in clinical trials

http://www.interceptpharma.com

An alternate approach is to

- develop an allosteric activator of the enzyme. Although

- development of an allosteric activator is not a typical pharmaceutical approach, recent studies indicate that this may be achievable aim(18).

References:

1. Cooke, J. P., and Ghebremariam, Y. T. : DDAH says NO to ADMA.(2011) Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology 31, 1462-1464

2. Tran, C. T., Leiper, J. M., and Vallance, P. : The DDAH/ADMA/NOS pathway.(2003) Atherosclerosis. Supplements 4, 33-40

3. Niebauer, J., Maxwell, A. J., Lin, P. S., Wang, D., Tsao, P. S., and Cooke, J. P.: NOS inhibition accelerates atherogenesis: reversal by exercise. (2003) American journal of physiology. Heart and circulatory physiology 285, H535-540

4. Miyazaki, H., Matsuoka, H., Cooke, J. P., Usui, M., Ueda, S., Okuda, S., and Imaizumi, T. : Endogenous nitric oxide synthase inhibitor: a novel marker of atherosclerosis.(1999) Circulation 99, 1141-1146

5. Wilson, A. M., Shin, D. S., Weatherby, C., Harada, R. K., Ng, M. K., Nair, N., Kielstein, J., and Cooke, J. P. (2010): Asymmetric dimethylarginine correlates with measures of disease severity, major adverse cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality in patients with peripheral arterial disease. Vasc Med 15, 267-274

6. Kielstein, J. T., Impraim, B., Simmel, S., Bode-Boger, S. M., Tsikas, D., Frolich, J. C., Hoeper, M. M., Haller, H., and Fliser, D. : Cardiovascular effects of systemic nitric oxide synthase inhibition with asymmetrical dimethylarginine in humans.(2004) Circulation 109, 172-177

7. Kielstein, J. T., Donnerstag, F., Gasper, S., Menne, J., Kielstein, A., Martens-Lobenhoffer, J., Scalera, F., Cooke, J. P., Fliser, D., and Bode-Boger, S. M. : ADMA increases arterial stiffness and decreases cerebral blood flow in humans.(2006) Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation 37, 2024-2029

8. Mittermayer, F., Krzyzanowska, K., Exner, M., Mlekusch, W., Amighi, J., Sabeti, S., Minar, E., Muller, M., Wolzt, M., and Schillinger, M. : Asymmetric dimethylarginine predicts major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with advanced peripheral artery disease.(2006) Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology 26, 2536-2540

9. Kakimoto, Y., and Akazawa, S.: Isolation and identification of N-G,N-G- and N-G,N’-G-dimethyl-arginine, N-epsilon-mono-, di-, and trimethyllysine, and glucosylgalactosyl- and galactosyl-delta-hydroxylysine from human urine. (1970) The Journal of biological chemistry 245, 5751-5758

10. Inoue, R., Miyake, M., Kanazawa, A., Sato, M., and Kakimoto, Y.: Decrease of 3-methylhistidine and increase of NG,NG-dimethylarginine in the urine of patients with muscular dystrophy. (1979) Metabolism: clinical and experimental 28, 801-804

11. Millward, D. J.: Protein turnover in skeletal muscle. II. The effect of starvation and a protein-free diet on the synthesis and catabolism of skeletal muscle proteins in comparison to liver. (1970) Clinical science 39, 591-603

12. Goldberg, A. L., and St John, A. C.: Intracellular protein degradation in mammalian and bacterial cells: Part 2. (1976) Annual review of biochemistry 45, 747-803

13. Dice, J. F., and Walker, C. D.: Protein degradation in metabolic and nutritional disorders. (1979) Ciba Foundation symposium, 331-350

14. Ogawa, T., Kimoto, M., and Sasaoka, K.: Purification and properties of a new enzyme, NG,NG-dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase, from rat kidney. (1989) The Journal of biological chemistry 264, 10205-10209

15. Ito, A., Tsao, P. S., Adimoolam, S., Kimoto, M., Ogawa, T., and Cooke, J. P.: Novel mechanism for endothelial dysfunction: dysregulation of dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase. (1999) Circulation 99, 3092-3095

16. Stuhlinger, M. C., Tsao, P. S., Her, J. H., Kimoto, M., Balint, R. F., and Cooke, J. P. : Homocysteine impairs the nitric oxide synthase pathway: role of asymmetric dimethylarginine.(2001) Circulation 104, 2569-2575

17. Sydow, K., Mondon, C. E., Schrader, J., Konishi, H., and Cooke, J. P.: Dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase overexpression enhances insulin sensitivity. (2008) Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology 28, 692-697

18. Zorn, J. A., and Wells, J. A.: Turning enzymes ON with small molecules. (2010) Nature chemical biology 6, 179-188

Other research papers on Nitric Oxide and Cardiac Risk were published on this Scientific Web site as follows:

The Nitric Oxide and Renal is presented in FOUR parts:

Part I: The Amazing Structure and Adaptive Functioning of the Kidneys: Nitric Oxide

Part II: Nitric Oxide and iNOS have Key Roles in Kidney Diseases

Part III: The Molecular Biology of Renal Disorders: Nitric Oxide

Part IV: New Insights on Nitric Oxide donors

Cardiac Arrhythmias: A Risk for Extreme Performance Athletes

What is the role of plasma viscosity in hemostasis and vascular disease risk?

Biochemistry of the Coagulation Cascade and Platelet Aggregation – Part I

Nitric Oxide Function in Coagulation

Nitric Oxide and iNOS have Key Roles in Kidney Diseases – Part II

Posted in Cell Biology, Signaling & Cell Circuits, Disease Biology, Small Molecules in Development of Therapeutic Drugs, HTN, Human Immune System in Health and in Disease, International Global Work in Pharmaceutical, Nitric Oxide in Health and Disease, Pharmaceutical Industry Competitive Intelligence, Systemic Inflammatory Response Related Disorders, tagged cytokine, Larry H. Bernstein, nephron, nitric oxide, Nitric oxide synthase, oxidative stress, Peroxinitrite, Renal function on November 26, 2012| 10 Comments »

Subtitle: Nitric Oxide, Peroxinitrite, and NO donors in Renal Function Loss

Curator and Author: Larry H. Bernstein, MD, FCAP

The Nitric Oxide and Renal is presented in FOUR parts:

Part I: The Amazing Structure and Adaptive Functioning of the Kidneys: Nitric Oxide

Part II: Nitric Oxide and iNOS have Key Roles in Kidney Diseases

Part III: The Molecular Biology of Renal Disorders: Nitric Oxide

Part IV: New Insights on Nitric Oxide donors

Conclusion to this series is presented in

The Essential Role of Nitric Oxide and Therapeutic NO Donor Targets in Renal Pharmacotherapy

Part II. Oxidative Stress and Regulating a Balance of Redox Potential is Central to Disordered Kidney Function

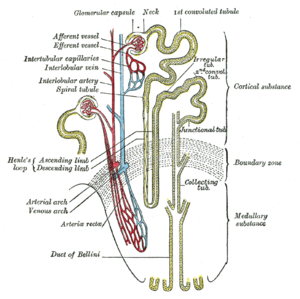

We have already described the key role that nitric oxide and the NO synthases play in reduction of oxidative stress. The balance that has to be regulated between pro- and anti-oxidative as well as inflammatory elements necessary for renal function, critically involves the circulation of the kidney. It poses an inherent risk in the kidney, where the existence of a rich circulatory and high energy cortical outer region surrounds a medullary inner portion that is engaged in the retention of water, the active transport of glucose, urea and uric acid nitrogenous waste, mineral balance and pH. In this discussion we shall look at kidney function, NO, and the large energy fluxes in the medullary tubules and interstitium. This is a continuation of of a series of posts on NO and NO related disorders, and the kidney in particular.

Part IIa. Nitric Oxide role in renal tubular epithelial cell function

Tubulointerstitial Nephritides

As part of the exponential growth in our understanding of nitric oxide (NO) in health and disease over the past 2 decades, the kidney has become appreciated as a major site where NO may play a number of important roles. Although earlier work on the kidney focused more on effects of NO at the level of larger blood vessels and glomeruli, there has been a rapidly growing body of work showing critical roles for NO in tubulointerstitial disease. In this review we discuss some of the recent contributions to this important field.

Mattana J, Adamidis A, Singhal PC. Nitric oxide and tubulointerstitial nephritides. Seminars in Nephrology 2004; 24(4):345-353.

Nitric oxide donors and renal tubular (subepithelial) matrix

Nitric oxide (NO) and its metabolite, peroxynitrite (ONOO-), are involved in renal tubular cell injury. If NO/ONOO- has an effect to reduce cell adhesion to the basement membrane, does this effect contribute to tubular obstruction and would it be partially responsible for the harmful effect of NO on the tubular epithelium during acute renal failure (ARF)?

Wangsiripaisan A, et al. examined the effect of the NO donors

- (z)-1-[2-(2-aminoethyl)-N-(2-ammonioethyl)amino]diazen-1- ium-1, 2-diolate (DETA/NO),

- spermine NONOate (SpNO), and

- the ONOO- donor 3-morpholinosydnonimine (SIN-1)

on cell-matrix adhesion to collagen types I and IV, and also fibronectin

using three renal tubular epithelial cell lines:

- LLC-PK1,

- BSC-1,

- OK.

It was only the exposure to SIN-1 that caused a dose-dependent impairment in cell-matrix adhesion. Similar results were obtained in the different cell types and matrix proteins. The effect of SIN-1 (500 microM) on LLC-PK1 cell adhesion was not associated with either cell death or alteration of matrix protein and was attenuated by either

- the NO scavenger 2-(4-carboxyphenyl)-4,4,5,5-tetramethylimidazoline-1-oxyl-3-oxide,

- the superoxide scavenger superoxide dismutase, or

- the ONOO- scavenger uric acid in a dose-dependent manner.

These investigators concluded in this seminal paper that ONOO- generated in the tubular epithelium during ischemia/reperfusion has the potential to impair the adhesion properties of tubular cells, which then may contribute to the tubular obstruction in ARF.

Wangsiripaisan A, Gengaro PE, Nemenoff RA, Ling H, et al. Effect of nitric oxide donors on renal tubular epithelial cell-matrix adhesion. Kidney Int 1999; 55(6):2281-8.

English: Reactions leading to generation of Nitric Oxide and Reactive Nitrogen Species. Novo and Parola Fibrogenesis & Tissue Repair 2008 1:5 doi:10.1186/1755-1536-1-5 (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Coexpressed Nitric Oxide Synthase and Apical β1 Integrins

In sepsis-induced acute renal failure, actin cytoskeletal alterations result in shedding of proximal tubule epithelial cells (PTEC) and tubular obstruction. This study examined the hypothesis that inflammatory cytokines, released early in sepsis, cause PTEC cytoskeletal damage and alter integrin-dependent cell-matrix adhesion. The question of whether the intermediate nitric oxide (NO) modulates these cytokine effects was also examined.

After exposure of human PTEC to

- tumor necrosis factor-α,

- interleukin-1α, and

- interferon-γ,

the actin cytoskeleton was disrupted and cells became elongated, with extension of long filopodial processes.

Cytokines induced shedding of

- viable,

- apoptotic, and

- necrotic PTEC,

which was dependent on NO synthesized by inducible NO synthase (iNOS) produced as a result of cytokine actions on PTEC.

Basolateral exposure of polarized PTEC monolayers to cytokines induced maximal NO-dependent cell shedding, mediated in part through NO effects on cGMP. Cell shedding was accompanied by dispersal of

- basolateral β1 integrins and

- E-cadherin,

with corresponding upregulation of integrin expression in clusters of cells elevated above the epithelial monolayer.

These cells demonstrated coexpression of iNOS and apically redistributed β1 integrins. These authors point out that the major ligand involved in cell anchorage was laminin, probably through interactions with the integrin α3β1. This interaction was downregulated by cytokines but was not dependent on NO. They posulate a mechanism by which inflammatory cytokines induce PTEC damage in sepsis, in the absence of hypotension and ischemia.

Glynne PA, Picot J and Evans TJ. Coexpressed Nitric Oxide Synthase and Apical β1 Integrins Influence Tubule Cell Adhesion after Cytokine-Induced Injury. JASN 2001; 12(11): 2370-2383.

Potentiation by Nitric Oxide of Apoptosis in Renal Proximal Tubule Cells

Proximal tubular epithelial cells (PTEC) exhibit a high sensitivity to undergo apoptosis in response to proinflammatory stimuli and immunosuppressors and participate in the onset of several renal diseases. This study examined the expression of inducible nitric oxide (NO) synthase after challenge of PTEC with bacterial cell wall molecules and inflammatory cytokines and analyzed the pathways that lead to apoptosis in these cells by measuring changes in the mitochondrial transmembrane potential and caspase activation.

The data show that the apoptotic effects of proinflammatory stimuli mainly were due to the expression of inducible NO synthase. Cyclosporin A and FK506 inhibited partially NO synthesis. However, both NO and immunosuppressors induced apoptosis, probably through a common mechanism that involved the irreversible opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Activation of caspases 3 and 7 was observed in cells treated with high doses of NO and with moderate concentrations of immunosuppressors. The conclusion is that the cooperation between NO and immunosuppressors that induce apoptosis in PTEC might contribute to the renal toxicity observed in the course of immunosuppressive therapy.

HORTELANO S, CASTILLA M, TORRES AM, TEJEDOR A, and BOSCÁ L. Potentiation by Nitric Oxide of Cyclosporin A and FK506- Induced Apoptosis in Renal Proximal Tubule Cells. J Am Soc Nephrol 2000; 11: 2315–2323.

Part IIb. Related studies with ROS and/or RNS on nonrenal epithelial cells

Reactive nitrogen species block cell cycle re-entry

Endogenous sources of reactive nitrogen species (RNS) act as second messengers in a variety of cell signaling events, whereas environmental sources of RNS like nitrogen dioxide (NO2) inhibit cell survival and growth through covalent modification of cellular macromolecules.

Murine type II alveolar cells arrested in G0 by serum deprivation were exposed to either NO2 or SIN-1, a generator of RNS, during cell cycle re-entry. In serum-stimulated cells, RNS blocked cyclin D1 gene expression, resulting in cell cycle arrest at the boundary between G0 and G1. Dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCF) fluorescence indicated that RNS induced sustained production of intracellular hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), which normally is produced only transiently in response to serum growth factors.

Loading cells with catalase prevented enhanced DCF fluorescence and rescued cyclin D1 expression and S phase entry.

These studies indicate environmental RNS interfere with cell cycle re-entry through an H2O2-dependent mechanism that influences expression of cyclin D1 and progression from G0 to the G1 phase of the cell cycle.

Yuan Z, Schellekens H, Warner L, Janssen-Heininger Y, Burch P, Heintz NH. Reactive nitrogen species block cell cycle re-entry through sustained production of hydrogen peroxide. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;28(6):705-12. Epub 2003 Jan 10.

Peroxynitrite modulates MnSOD gene expression

Peroxynitrite (ONOO-) is a strong oxidant derived from nitric oxide (‘NO) and superoxide (O2.-), reactive nitrogen (RNS) and oxygen species (ROS) present in inflamed tissue. Other oxidant stresses, e.g., TNF-alpha and hyperoxia, induce mitochondrial, manganese-containing superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) gene expression.

3-morpholinosydnonimine HCI (SIN-1) (10 or 1000 microM) increased MnSOD mRNA, but did not change hypoxanthine guanine phosphoribosyl transferase (HPRT) mRNA.

Authentic peroxynitrite (ONOO ) (100-500 microM) also increased MnSOD mRNA but did not change constitutive HPRT mRNA expression. ONOO stimulated luciferase gene expression driven by a 2.5 kb fragment of the rat MnSOD gene 5′ promoter region.

MnSOD gene induction due to ONOO- was inhibited effectively by L-cysteine (10 mM) and partially inhibited by N-acetyl cysteine (50 mM) or pyrrole dithiocarbamate (10 mM).

.NO from 1-propanamine, 3-(2-hydroxy-2-nitroso-1-propylhydrazine) (PAPA NONOate) (100 or 1000 microM) did not change MnSOD or HPRT mRNA, nor did either H202 or NO2-, breakdown products of SIN-1 and ONOO, have any effect on MnSOD mRNA expression; ONOO- and SIN-1 also did not increase detectable MnSOD protein content or increase MnSOD enzymatic activity.

Nevertheless, increased steady state [O2.-] in the presence of .NO yields ONOO , and ONOO has direct, stimulatory effects on MnSOD transcript expression driven at the MnSOD gene 5′ promoter region inhibited completely by L-cysteine and partly by N-acetyl cysteine in lung epithelial cells. This raises a question of whether the same effect is seen in renal tubular epithelium.

Jackson RM, Parish G, Helton ES. Peroxynitrite modulates MnSOD gene expression in lung epithelial cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 1998; 25(4-5):463-72.

Comparative impacts of glutathione peroxidase-1 gene knockout on oxidative stress

Selenium-dependent glutathione peroxidase-1 (GPX1) protects against reactive-oxygen-species (ROS)-induced oxidative stress in vivo, but its role in coping with reactive nitrogen species (RNS) is unclear. Primary hepatocytes were isolated from GPX1-knockout (KO) and wild-type (WT) mice to test protection of GPX1 against cytotoxicity of

- superoxide generator diquat (DQ),

- NO donor S-nitroso-N-acetyl-penicillamine (SNAP) and

- peroxynitrite generator 3-morpholinosydnonimine (SIN-1).

Treating cells with SNAP (0.1 or 0.25 mM) in addition to DQ produced synergistic cytotoxicity that minimized differences in apoptotic cell death and oxidative injuries between the KO and WT cells. Less protein nitrotyrosine was induced by 0.05-0.5 mM DQ+0.25 mM SNAP in the KO than in the WT cells.

Total GPX activity in the WT cells was reduced by 65 and 25% by 0.5 mM DQ+0.1 mM SNAP and 0.5 mM DQ, respectively.

Decreases in Cu,Zn-superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity and increases in Mn-SOD activity in response to DQ or DQ+SNAP were greater in the KO cells than in the WT cells.

The study indicates GPX1 was more effective in protecting hepatocytes against oxidative injuries mediated by ROS alone than by ROS and RNS together, and knockout of GPX1 did not enhance cell susceptibility to RNS-associated cytotoxicity. Instead, it attenuated protein nitration induced by DQ+SNAP.

To better understand the mechanism(s) underlying nitric oxide (. NO)-mediated toxicity, in the presence and absence of concomitant oxidant exposure, postmitotic terminally differentiated NT2N cells, which are incapable of producing . NO, were exposed to PAPA-NONOate (PAPA/NO) and 3-morpholinosydnonimine (SIN-1).

Exposure to SIN-1, which generated peroxynitrite (ONOO) in the range of 25-750 nM/min, produced a concentration- and time-dependent delayed cell death.

In contrast, a critical threshold concentration (>440 nM/min) was required for . NO to produce significant cell injury.

There is a largely necrotic lesion after ONOO exposure and an apoptotic-like morphology after . NO exposure. Cellular levels of reduced thiols correlated with cell death, and pretreatment with N-acetylcysteine (NAC) fully protected from cell death in either PAPA/NO or SIN-1 exposure.

NAC given within the first 3 h posttreatment further delayed cell death and increased the intracellular thiol level in SIN-1 but not . NO-exposed cells.

Cell injury from . NO was independent of cGMP, caspases, and superoxide or peroxynitrite formation.

Overall, exposure of non-. NO-producing cells to . NO or peroxynitrite results in delayed cell death, which, although occurring by different mechanisms,

appears to be mediated by the loss of intracellular redox balance.

Gow AJ, Chen Q, Gole M, Themistocleous M, Lee VM, Ischiropoulos H. Two distinct mechanisms of nitric oxide-mediated neuronal cell death show thiol dependency. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2000; 278(6):C1099-107.

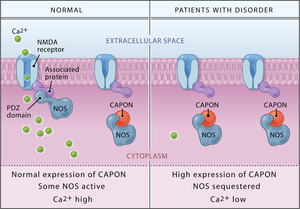

English: Binding of CAPON results in a reduction of NMDA receptor/nitric oxide synthase (NOS) complexes, leading to decreased NMDA receptor–gated calcium influx and a catalytically inactive nitric oxide synthase. Overexpression of either the full-length or the novel shortened CAPON isoform as reported by Brzustowicz and colleagues is, therefore, predicted to lead to impaired NMDA receptor–mediated glutamate neurotransmission. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

NO2 effect on phosphatidyl choline

Nitrogen dioxide (NO2) inhalation affects the extracellular surfactant as well as the structure and function of type II pneumocytes. The studies had differences in oxidant concentration, duration of exposure, and mode of NO2 application.

This study evaluated the influence of the NO2 application mode on the phospholipid metabolism of type II pneumocytes . Rats were exposed to identical NO2 body doses (720 ppm x h), which were applied continuously (10 ppm for 3 d), intermittently (10 ppm for 8 h per day, for 9 d), and repeatedly (10 ppm for 3 d, 28 d rest, and then 10 ppm for 3 d). Immediately after exposure, type II cells were isolated and evaluated for

- cell yield,

- vitality,

- phosphatidylcholine (PC) synthesis, and

- secretion.

Type II pneumocyte cell yield was only increased from animals that had been continuously exposed to NO2, but vitality of the isolated type II pneumocytes was not affected by the NO2 exposure modes. Continuous application of 720 ppm x h NO2 resulted in increased activity of the cytidine-5-diphosphate (CDP)-choline pathway.

- After continuous NO2 application,

- specific activity of choline kinase,

- cytidine triphosphate (CTP):cholinephosphate cytidylyltransferase,

- uptake of choline, and

- pool sizes of CDP-choline and PC

were significantly increased over those of controls.

Intermittent application of this NO2 body dose provoked less increase in PC synthesis and the synthesis parameters were comparable to those for cells from control animals after repeated exposure. Whereas PC synthesis in type II cells was stimulated by NO2, their secretory activity was reduced. Continuous exposure reduced the secretory activity most, whereas intermittent exposure nonsignificantly reduced this activity as compared with that of controls. The repeated application of NO2 produced no differences.

The authors conclude that type II pneumocytes adapt to NO2 atmospheres depending on the mode of its application, at least for the metabolism of PC and its secretion from isolated type II pneumocytes. Further studies are necessary to determine whether additional metabolic activities will also adapt to NO2 atmospheres, and if these observations are specific for NO2 or represent effects generally due to oxidants. The reader, however, asks whether this effect could also be found in renal epithelial cells, for which PC is not considered vital as for type II pneumocytes and possibly related to surfactant activity in the lung.

Müller B, Seifart C, von Wichert P, Barth PJ. Adaptation of rat type II pneumocytes to NO2: effects of NO2 application mode on phosphatidylcholine metabolism. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1998; 18(5): 712-20.

iNOS involved in immediate response to anaphylaxis

The generation of large quantities of nitric oxide (NO) is implicated in the pathogenesis of anaphylactic shock. The source of NO, however, has not been established and conflicting results have been obtained when investigators have tried to inhibit its production in anaphylaxis.

This study analyzed the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) in a mouse model of anaphylaxis.

BALB/c mice were sensitized and challenged with ovalbumin to induce anaphylaxis. Tissues were removed from the heart and lungs, and blood was drawn at different time points during the first 48 hours after induction of anaphylaxis. The Griess assay was used to measure nitric oxide generation. Nitric oxide synthase expression was examined by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction and immunohistochemistry.

A significant increase in iNOS mRNA expression and nitric oxide production was evident as early as 10 to 30 minutes after allergen challenge in both heart and lungs. In contrast, expression of eNOS mRNA was not altered during the course of the experiment.

The results support involvement of iNOS in the immediate physiological response of anaphylaxis.

Sade K, Schwartz IF, Etkin S, Schwartzenberg S, et al. Expression of Inducible Nitric Oxide

Synthase in a Mouse Model of Anaphylaxis. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 2007; 17(6):379-385.

Part IIc. Additional Nonrenal Related NO References

Nitrogen dioxide induces death in lung epithelial cells in a density-dependent manner.

Persinger RL, Blay WM, Heintz NH, Hemenway DR, Janssen-Heininger YM.

Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2001 May;24(5):583-90.

PMID: 11350828 [PubMed – indexed for MEDLINE] Free Article

2.

Molecular mechanisms of nitrogen dioxide induced epithelial injury in the lung.

Persinger RL, Poynter ME, Ckless K, Janssen-Heininger YM.

Mol Cell Biochem. 2002 May-Jun;234-235(1-2):71-80. Review.

PMID: 12162462 [PubMed – indexed for MEDLINE]

3.

Nitric oxide and peroxynitrite-mediated pulmonary cell death.

Gow AJ, Thom SR, Ischiropoulos H.

Am J Physiol. 1998 Jan;274(1 Pt 1):L112-8.

PMID: 9458808 [PubMed – indexed for MEDLINE] Free Article

4.

Mitogen-activated protein kinases mediate peroxynitrite-induced cell death in human bronchial epithelial cells.

Nabeyrat E, Jones GE, Fenwick PS, Barnes PJ, Donnelly LE.

Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003 Jun;284(6):L1112-20. Epub 2003 Feb 21.

PMID: 12598225 [PubMed – indexed for MEDLINE] Free Article

5.

Peroxynitrite inhibits inducible (type 2) nitric oxide synthase in murine lung epithelial cells in vitro.

Robinson VK, Sato E, Nelson DK, Camhi SL, Robbins RA, Hoyt JC.

Free Radic Biol Med. 2001 May 1;30(9):986-91.

PMID: 11316578 [PubMed – indexed for MEDLINE]

6.

Nitric oxide-mediated chondrocyte cell death requires the generation of additional reactive oxygen species.

Del Carlo M Jr, Loeser RF.

Arthritis Rheum. 2002 Feb;46(2):394-403.

PMID: 11840442 [PubMed – indexed for MEDLINE]

7.

Colon epithelial cell death in 2,4,6-trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid-induced colitis is associated with increased inducible nitric-oxide synthase expression and peroxynitrite production.

Yue G, Lai PS, Yin K, Sun FF, Nagele RG, Liu X, Linask KK, Wang C, Lin KT, Wong PY.

J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001 Jun;297(3):915-25.

PMID: 11356911 [PubMed – indexed for MEDLINE] Free Article

Summary

In this piece I have covered the conflicting roles of endogenous end inducible nitric oxide (eNOS and iNOS) in the reaction to reactive oxygen and nitrogen stress (ROS, RNS), and many experiments directed at sorting out these effects using continuous and intermittent delivery of NO2, production of ONOO- from .NO, and several agents that are used to upregulate and downregulate the underlying mechanism of response. These investigations are not only carried out in experiments on renal function and apoptosis, but also there are similar examples taken from studies of lung and liver. This forms a backdrop for the assessment of renal diseases:

- immune related

- acute traumatic injury

- chronic

The continuation of the discussion will be in essays that follow.

Related articles

- Differential Distribution of Nitric Oxide – A 3-D Mathematical Model (pharmaceuticalintelligence.com)

- Low Bioavailability of Nitric Oxide due to Misbalance in Cell Free Hemoglobin in Sickle Cell Disease – A Computational Model (pharmaceuticalintelligence.com)

- Crucial role of Nitric Oxide in Cancer (pharmaceuticalintelligence.com)

- Nitric Oxide and Immune responses: part 1 (pharmaceuticalintelligence.com)

- Nitric Oxide and Sepsis, Hemodynamic Collapse, and the Search for Therapeutic Options (pharmaceuticalintelligence.com)

- Statins’ nonlipid effects on vascular endothelium through eNOS activation (pharmaceuticalintelligence.com)

- Nitric Oxide and Immune Responses: Part 2 (pharmaceuticalintelligence.com)

New Insights on Nitric Oxide donors – Part IV

Posted in Biological Networks, Gene Regulation and Evolution, Biomarkers & Medical Diagnostics, Cell Biology, Signaling & Cell Circuits, Chemical Biology and its relations to Metabolic Disease, Disease Biology, Small Molecules in Development of Therapeutic Drugs, Genome Biology, HTN, Human Immune System in Health and in Disease, Metabolomics, Nitric Oxide in Health and Disease, Pharmaceutical Industry Competitive Intelligence, Proteomics, Stem Cells for Regenerative Medicine, Systemic Inflammatory Response Related Disorders, tagged Cell Biology, Larry H. Bernstein, nitric oxide, Nitric oxide synthase, Peroxinitrite, Reactive oxygen species, Renal function on November 26, 2012| 9 Comments »

Subtitle: Nitric Oxide, Peroxinitrite, and NO donors in Renal Function Loss

Curator and Author: Larry H. Bernstein, MD, FCAP

The Nitric Oxide and Renal is presented in FOUR parts:

Part I: The Amazing Structure and Adaptive Functioning of the Kidneys: Nitric Oxide

Part II: Nitric Oxide and iNOS have Key Roles in Kidney Diseases

Part III: The Molecular Biology of Renal Disorders: Nitric Oxide

Part IV: New Insights on Nitric Oxide donors

Conclusion to this series is presented in

The Essential Role of Nitric Oxide and Therapeutic NO Donor Targets in Renal Pharmacotherapy

The criticality of renal function is easily overlooked until significant loss of nephron mass is overtly seen. The kidneys become acutely and/or chronically dysfunctional in metabolic, systemic inflammatory and immunological diseases of man. We have described how the key role that nitric oxide and the NO synthases (eNOS and iNOS) play competing roles in reduction or in the genesis of reactive oxygen species. There is a balance to be struck between pro- and anti-oxidative as well as inflammatory elements for avoidance of diseases, specifically involving the circulation, but effectively not limited to any organ system. In this discussion we shall look at kidney function, NO and NO donors. This is an extension of a series of posts on NO and NO related disorders.

Part IV. New Insights on NO donors

This study investigated the involvement of nitric oxide (NO) into the irradiation-induced increase of cell attachment. These experiments explored the cellular mechanisms of low-power laser therapy.

HeLa cells were irradiated with a monochromatic visible-tonear infrared radiation (600–860 nm, 52 J/m2) or with a diode laser (820 nm, 8–120 J/m2) and the number of cells attached to a glass matrix was counted after 30 minute incubation at 37oC. The NO donors

- sodium nitroprusside (SNP),

- glyceryl trinitrate (GTN), or

- sodium nitrite (NaNO2)

were added to the cellular suspension before or after irradiation. The action spectra and the concentration and fluence dependencies obtained were compared and analyzed. The well-structured action spectrum for the increase of the adhesion of the cells, with maxima at 619, 657, 675, 740, 760, and 820 nm, points to the existence of a photoacceptor responsible for the enhancement of this property (supposedly cytochrome c oxidase, the terminal respiratory chain enzyme), as well as signaling pathways between the cell mitochondria, plasma membrane, and nucleus. Treating the cellular suspension with SNP before irradiation significantly modifies the action spectrum for the enhancement of the cell attachment property (band maxima at 642, 685, 700, 742, 842, and 856 nm).

The action of SNP, GTN, andNaNO2 added before or after irradiation depends on their concentration and radiation fluence.

The NO donors added to the cellular suspension before irradiation eliminate the radiation induced increase in the number of cells attached to the glass matrix, supposedly by way of binding NO to cytochrome c oxidase. NO added to the suspension after irradiation can also inhibit the light-induced signal downstream. Both effects of NO depend on the concentration of the NO donors added. The results indicate that NO can control the irradiation-activated reactions that increase the attachment of cells.

Karu TI, Pyatibrat LV, and Afanasyeva NI. Cellular Effects of Low Power Laser Therapy Can be Mediated by Nitric Oxide. Lasers Surg. Med 2005; 36:307–314.

Interferon a-2b (IFN-a) effect on barrier function of renal tubular epithelium

IFNa treatment can be accompanied by impaired renal function and capillary leak. This study shows IFNa produced dose-dependent and time-dependent decrease in transepithelial resistance (TER) ameliorated by tyrphostin, an inhibitor of phosphotyrosine kinase with increased expression of occludin and E-cadherin. In conclusion, IFNa can directly affect barrier function in renal epithelial cells via overexpression or missorting of the junctional proteins occludin and E-cadherin.

Lechner J, Krall M, Netzer A, Radmayr C, et al. Effects of interferon a-2b on barrier function and junctional complexes of renal proximal tubular LLC-pK1 cells. Kidney Int 1999; 55:2178-2191.

Ischemia-reperfusion injury

The pathophysiology of acute renal failure (ARF) is complex and not well understood. Numerous models of ARF suggest that oxygen-derived reactive species are important in renal ischemia-reperfusion (I-R) injury, but the nature of the mediators is still controversial. Treatment with

- oxygen radical scavengers,

- antioxidants, and

- iron chelators such as

- superoxide dismutase,

- dimethylthiourea,

- allopurinol, and

- deferoxamine

are protective in some models, and suggest a role for the hydroxyl radical formation. However, these compounds are not protective in all models of I-R injury, and direct evidence for the generation of hydroxyl radical is absent. Furthermore, these inhibitors have another property in common. They all directly scavenge or inhibit the formation of peroxynitrite (ONOO−), a highly toxic species derived from nitric oxide (NO) and superoxide. Thus, the protective effects seen with these inhibitors may be due in part to their ability to inhibit ONOO− formation.

Even though reactive oxygen species are thought to participate in ischemia-reperfusion (I-R) injury, induction of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and production of high levels of nitric oxide (NO) also contribute to this injury. NO can combine with superoxide to form the potent oxidant peroxynitrite (ONOO−). NO and ONOO− were investigated in a rat model of renal I-R injury using the selective iNOS inhibitor L-N6-(1-iminoethyl)lysine (L-NIL).

I-R surgery significantly increased plasma creatinine levels to 1.9 ± 0.3 mg/dl (P < .05) and caused renal cortical necrosis. L-NIL administration (3 mg/kg) in animals subjected to I-R significantly decreased plasma creatinine levels to 1.2 ± 0.10 mg/dl (P < .05 compared with I-R) and reduced tubular damage.

ONOO− formation was evaluated by detecting 3-nitrotyrosine-protein adducts, a stable biomarker of ONOO− formation.

- The kidneys from I-R animals had increased levels of 3-nitrotyrosine-protein adducts compared with control animals

- L-NIL-treated rats (3 mg/kg) subjected to I-R showed decreased levels of 3-nitrotyrosine-protein adducts.

These results support the hypothesis that iNOS-generated NO mediates damage in I-R injury possibly through ONOO− formation.

In summary, 3-nitrotyrosine-protein adducts were detected in renal tubules after I-R injury. Selective inhibition of iNOS by L-NIL

- decreased injury,

- improved renal function, and

- decreased apparent ONOO− formation.

Reactive nitrogen species should be considered potential therapeutic targets in the prevention and treatment of renal I-R injury.

Walker LM, Walker PD, Imam SZ, et al. Evidence for Peroxynitrite Formation in Renal Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury: Studies with the Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase InhibitorL-N6-(1-Iminoethyl)-lysine1. 2000.

Role of TNFa independent of iNOS

Renal failure is a frequent complication of sepsis, mediated by renal vasoconstrictors and vasodilators. Endotoxin induces several proinflammatory cytokines, among which tumor necrosis factor (TNF) is thought to be of major importance. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) has been suggested to be a factor in the acute renal failure in sepsis or endotoxemia. Passive immunization by anti-TNFa prevented development of septic shock in animal experiments. The development of ARF involves excessive intrarenal vasoconstriction.

Recent studies also suggest involvement of nitric oxide (NO), generated by inducible NO synthase (iNOS), in the pathogenesis of endotoxin-induced renal failure. TNF-a leads to a decrease in glomerular filtration rate (GFR). The present study tested the hypothesis that the role of TNF-a in endotoxic shock related ARF is mediated by iNOS-derived NO.

An injection of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) constituent of gram-negative bacteria to wild-type mice resulted in a 70% decrease in glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and in a 40% reduction in renal plasma flow (RPF) 16 hours after the injection.

The results occurred independent of

- hypotension,

- morphological changes,

- apoptosis, and

- leukocyte accumulation.

In mice pretreated with TNFsRp55, only a 30% decrease in GFR was observed without a significant change in RPF as compared with controls.

Effect of TNFsRp55 (10 mg/kg IP) on renal function in wild-type mice.

Mice were pretreated with TNFsRp55 for one hour before the administration of 5 mg/kg intraperitoneal endotoxin. GFR (A) and RPF (B) were determined 16 hours thereafter. Data are expressed as mean 6, SEM, N 5 6. *P , 0.05 vs. Control; §P , 0.05 vs. LPS, by ANOVA.

The serum NO concentration was significantly lower in endotoxemic wild-type mice pretreated with TNFsRp55, as compared with untreated endotoxemic wild-type mice. In LPS-injected iNOS knockout mice and wild-type mice treated with a selective iNOS inhibitor, 1400W, the development of renal failure was similar to that in wild-type mice. As in wild-type mice,TNFsRp55 significantly attenuated the decrease in GFR (a 33% decline, as compared with 75% without TNFsRp55) without a significant change in RPF in iNOS knockout mice given LPS.

These results demonstrate a role of TNF in the early renal dysfunction (16 h) in a septic mouse model independent of

- iNOS,

- hypotension,

- apoptosis,

- leukocyte accumulation,and

- morphological alterations,

thus suggesting renal hypoperfusion secondary to an imbalance between, as yet to be defined renal vasoconstrictors and vasodilators.

Knotek M, Rogachev B, Wang W,….., Edelstein CL, Dinarello CA, and Schrier RW. Endotoxemic renal failure in mice: Role of tumor necrosis factor independent of inducible nitric oxide synthase. Kidney International 2001; 59:2243–2249

Ischemic acute renal failure

Inflammation plays a major role in the pathophysiology of acute renal failure resulting from ischemia. In this review, we discuss the contribution of endothelial and epithelial cells and leukocytes to this inflammatory response. The roles of cytokines/chemokines in the injury and recovery phase are reviewed. The ability of the mouse kidney to be protected by prior exposure to ischemia or urinary tract obstruction is discussed as a potential model to emulate as we search for pharmacologic agents that will serve to protect the kidney against injury.

the inflammatory mediators produced by tubular epithelial cells and activated leukocytes in renal ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury.

Tubular epithelia produce TNF-a, IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, TGF-b, MCP-1, ENA-78, RANTES, and fractalkines, whereas leukocytes produce TNF-a, IL-1, IL-8, MCP-1, ROS, and eicosanoids. The release of these chemokines and cytokines serve as effectors for a positive feedback pathway enhancing inflammation and cell injury

the cycle of tubular epithelial cell injury and repair following renal ischemia/reperfusion.

Tubular epithelia are typically cuboidal in shape and apically-basally polarized; the Na+/K+-ATPase localizes to basolateral plasma membranes, whereas cell adhesion molecules, such as integrins localize basally. In response to ischemia reperfusion, the Na+/K+-ATPase appears apically, and integrins are detected on lateral and basal plasma membranes.

Some of the injured epithelial cells undergo necrosis and/or apoptosis detaching from the underlying basement membrane into the tubular space where they contribute to tubular occlusion. Viable cells that remain attached,

- dedifferentiate,

- spread, and

- migrate to

- repopulate the denuded basement membrane.

With cell proliferation, cell-cell and cell-matrix contacts are restored, and the epithelium redifferentiates and repolarizes, forming a functional, normal epithelium

Inflammation is a significant component of renal I/R injury, playing a considerable role in its pathophysiology. Although significant progress has been made in defining the major components of this process, the complex cross-talk between endothelial cells, inflammatory cells, and the injured epithelium with each generating and often responding to cytokines and chemokines is not well understood. In addition, we have not yet taken full advantage of the large body of data on inflammation in other organ systems.

Furthermore, preconditioning the kidney to afford protection to subsequent bouts of ischemia may serve as a useful model challenging us to therapeutically mimic endogenous mechanisms of protection. Understanding the inflammatory response prevalent in ischemic kidney injury will facilitate identification of molecular targets for therapeutic intervention.

Bonventre JV and Zuk A. Ischemic acute renal failure: An inflammatory disease? Forefronts in Nephrology 2002;.. :480-485

Gene expression profiles in renal proximal tubules

In kidney disease renal proximal tubular epithelial cells (RPTEC) actively contribute to the progression of tubulointerstitial fibrosis by mediating both an inflammatory response and via epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Using laser capture microdissection we specifically isolated RPTEC from cryosections of the healthy parts of kidneys removed owing to renal cell carcinoma and from kidney biopsies from patients with proteinuric nephropathies. RNA was extracted and hybridized to complementary DNA microarrays after linear RNA amplification. Statistical analysis identified 168 unique genes with known gene ontology association, which separated patients from controls.

Besides distinct alterations in signal-transduction pathways (e.g. Wnt signalling), functional annotation revealed a significant upregulation of genes involved in

- cell proliferation and cell cycle control (like insulin-like growth factor 1 or cell division cycle 34),

- cell differentiation (e.g. bone morphogenetic protein 7),

- immune response,

- intracellular transport and

- metabolism

in RPTEC from patients.

On the contrary we found differential expression of a number of genes responsible for cell adhesion (like BH-protocadherin) with a marked downregulation of most of these transcripts. In summary, our results obtained from RPTEC revealed a differential regulation of genes, which are likely to be involved in

- either pro-fibrotic or

- tubulo-protective mechanisms

in proteinuric patients at an early stage of kidney disease.

Rudnicki M, Eder S, Perco P, Enrich J, et al. Gene expression profiles of human proximal tubular epithelial cells in proteinuric nephropathies. Kidney International 2006; xx:1-11.

Kidney International advance online publication, 20 December 2006; doi:10.1038/sj.ki.5002043. http://www.kidney-international.org

Oxidative stress involved in diabetic nephropathy

Diabetic Nephropathy (DN) poses a major health problem. There is strong evidence for a potential role of the eNOS gene. The aim of this case control study was to investigate the possible role of genetic variants of the endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase (eNOS) gene and oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of nephropathy in patients with diabetes mellitus.

The study included 124 diabetic patients;

- 68 of these patients had no diabetic nephropathy (group 1) while

- 56 patients exhibited symptoms of diabetic nephropathy (group 2).

- Sixty two healthy non-diabetic individuals were also included as a control group.

Blood samples from subjects and controls were analyzed to investigate the eNOS genotypes and to estimate the lipid profile and markers of oxidative stress such as malondialdehyde (MDA) and nitric oxide (NO). No significant differences were found in the frequency of eNOS genotypes between diabetic patients (either in group 1 or group 2) and controls (p >0.05).

Also, no significant differences were found in the frequency of eNOS genotypes between group 1 and group 2 (p >0.05).

Both group 1 and group 2 had significantly higher levels of nitrite and MDA when compared with controls (all p = 0.0001). Also group 2 patients had significantly higher levels of nitrite and MDA when compared with group 1 (p = 0.02, p = 0.001 respectively).

The higher serum level of the markers of oxidative stress in diabetic patients particularly those with diabetic nephropathy suggest that oxidative stress and not the eNOS gene polymorphism is involved in the pathogenesis of the diabetic nephropathy in this subset of patients

Badawy A, Elbaz R, Abbas AM, Ahmed Elgendy A, et al. Oxidative stress and not endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase gene polymorphism involved in diabetic nephropathy. Journal of Diabetes and Endocrinology 2011; 2(3): 29-35.

Metformin in renal ischemia reperfusion

Renal ischemia plays an important role in renal impairment and transplantation.

Metformin is a biguanide used in type 2 diabetes, it inhibits hepatic glucose production and increases peripheral insulin sensitivity. While the mode of action of metformin is incompletely understood, it appears to have anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects involved in its beneficial effects on insulin resistance.

Control, Sham, ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) and Metformin treated I /R groups

A renal I/R injury was done by a left renal pedicle occlusion to induce ischemia for 45 min followed by 60 min of reperfusion with contralateral nephrectomy. Metformin pretreated I/R rats in a dose of 200 mg/kg/day for three weeks before ischemia induction.

Nitric oxide (NO), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF α) , catalase (CAT) and reduced glutathione (GSH) activities were determined in renal tissue, while creatinine clearance (CrCl) , blood urea nitrogen (BUN) were measured and 5 hour urinary volume and electrolytes were estimated .

BUN and CrCl levels in the I/R group were significantly higher than in control rats (p<0.05) table (1).

Table 1: Creatinine clearance (Cr Cl) and blood urea nitrogen( BUN) levels in control and test groups. Mean ± SD.

| Groups | CrCl (ml/min) | BUN mg/dl |

| Control group | 1.30 ±0.11 | 14.30±0.25 |

| Sham group+metformin | 1.27±0.09 | 15.70±0.19 |

| I/R group P1 | 1.85±0.25<0.001*** | 28.00±0.62<0.001*** |

| I/R+metformin group P2 P3 | 1.55±0.220.001**0.028* | 18.10±1.00<0.001***<0.001*** |

P1: Statistical significance between control group and saline treated I/R group.

P2 Statistical significance between control group and Metformin treated I/R group.

P3 Statistical significance between saline treated I/R group and Metformin treated I/R group.

When metformin was administered before I/R, BUN and CrCl levels were still significantly higher than control group but their elevation were significantly lower in comparison to I/R group alone (P<0.05).

TNF α and NO levels were significantly higher in the I/R group than those of the control group (Table 2).

Pre-treatment with metformin significantly lowered their levels in comparison to I/R group (P<0.05).

Table 2: Tumour necrosis factior α (TNF α)and inducible nitric oxide (iNO)levels in control and test groups. (Mean ± SD).

| Groups | TNF α (pmol/mg tissue) | iNO nmol/ mg tissue |

| Control group | 17.60 ±5.98 | 2.54 ± 0.82 |

| Sham group+ metformin | 16.70 ±5.50 | 2.35 ±0.80 |

| I/R group P1 | 54. 00±6.02<0.001*** | 4.50±0.89<0.001** |

| I/R+ metformin group P2 P3 | 39 ± 14.01<0.001***0.006** | 3.53±0.950.02*0.03* |

P1: Statistical significance between control group and saline treated I/R group.

P2 Statistical significance between control group and Metformin treated I/R group.

P3 Statistical significance between saline treated I/R group and Metformin treated I/R group

These results showed significant increase in

- NO,

- TNF α,

- BUN ,

- CrCl and

significant decrease in

- urinary volume ,

- electrolytes,

- CAT and

- GSH activities

in the I/R group than those in the control group.

Metformin

- decreased significantly NO, TNF α, BUN and CrCl while

- increased urinary volume, electrolytes, CAT and GSH activities.

Lipid peroxidation is related to I/R induced tissue injury. Production of inducible NO synthase (NOS) under lipid peroxidation and inflammatory conditions results in the induction of NO

which react with

- O2

- liberating peroxynitrite (OONO–).

NO itself inactivates the antioxidant enzyme system CAT and GSH.

Alteration in NO synthesis have been observed in other kidney injuries as nephrotoxicity and acute renal failure induced by endotoxins. Treatment with iNOS inhibitors improved renal function and decreased peroxynitrite radical which is believed to be responsible for the shedding of proximal convoluted tubules in I/R.

Metformin produced anti-inflammatory renoprotective effect on CrCl and diuresis in renal I/R injury.

Malek HA. The possible mechanism of action of metformin in renal ischemia reperfusion in rats. The Pharma Research Journal 2011; 6(1):42-49.

Possible role of NO donors in ARF

The L-arginine-nitric oxide (NO) pathway has been implicated in many physiological functions in the kidney, including

- regulation of glomerular hemodynamics,

- mediation of pressure-natriuresis,

- maintenance of medullary perfusion,

- blunting of tubuloglomerular feedback (TGF),

- inhibition of tubular sodium reabsorption and

- modulation of renal sympathetic nerve activity.

Its net effect in the kidney is to promote natriuresis and diuresis, contributing to adaptation to variations of dietary salt intake and maintenance of normal blood pressure.

| RAS | Renal hemodynamics | Sodium balance |

| Medullary perfusion | ||

| Pressure-natriuresis | ||

| Salt intake | Tubulo-glomerular feedback | Blood pressure |

| Tubular sodium reabsorption | ||

| Blood pressure | Renal sympathetic activity | Regulation |

| Extrarenal factors | Intrarenal functions | Physiological roles |

Role of nitric oxide in renal physiology. RAS, renin-angiotensin system

Nitric oxide has been implicated in many physiologic processes that influence both acute and long-term control of kidney function. Its net effect in the kidney is to promote natriuresis and diuresis, contributing to adaptation to variations of dietary salt intake and maintenance of normal blood pressure. A pretreatment with nitric oxide donors or L-arginine may prevent the ischemic acute renal injury. In chronic kidney diseases, the systolic blood pressure is correlated with the plasma level of asymmetric dimethylarginine, an endogenous inhibitor of nitric oxide synthase.

A reduced production and biological action of nitric oxide is associated with an elevation of arterial pressure, and conversely, an exaggerated activity may represent a compensatory mechanism to mitigate the hypertension.

JongUn Lee. Nitric Oxide in the Kidney : Its Physiological Role and Pathophysiological Implications. Electrolyte & Blood Pressure 2008; 6:27-34.

Renal Hypoxia and Dysoxia following Reperfusion

Acute renal failure (ARF) is a common condition which develops in 5% of hospitalized patients. Of the patients who develop ARF, ~10% eventually require renal replacement therapy. Among critical care patients who have acute renal failure and survive, 2%-10% develop terminal renal failure and require long-term dialysis.

The kidneys are particularly susceptible to ischemic injury in many clinical conditions such as renal transplantation, treatment of suprarenal aneurysms, renal artery reconstructions, contrast-agent induced nephropathy, cardiac arrest, and shock. One reason for renal sensitivity to ischemia is that the kidney microvasculature is highly complex and must meet a high energy demand. Under normal, steady state conditions, the oxygen (O2) supply to the renal tissues is well in excess of oxygen demand.

Under pathological conditions, the delicate balance of oxygen supply versus demand is easily disturbed due to the unique arrangement of the renal microvasculature and its increasing numbers of diffusive shunting pathways.

The renal microvasculature is serially organized, with almost all descending vasa recta emerging from the efferent arterioles of the juxtamedullary glomeruli. Adequate tissue oxygenation is thus partially dependent on the maintenance of medullary perfusion by adequate cortical perfusion. This, combined with the low amount of medullary blood flow (~10% of total renal blood flow) in the U-shaped microvasculature of the medulla allows O2 shunting between the descending and ascending vasa recta and contributes to the high sensitivity of the medulla and cortico-medullary junction to decreased O2 supply.

Whereas past investigations have focused mainly on tubular injury as the main cause of ischemia-related acute renal failure, increasing evidence implicates alterations in the intra-renal microcirculation pathway and in the O2 handling. Indeed, although acute tubular necrosis (ATN) has classically been believed to be the leading cause of ARF, data from biopsies in patients with ATN have shown few or no changes consistent with tubular necrosis. The role played by microvascular dysfunction, however, has generated increasing interest. The complex pathophysiology of ischemic ARF includes the inevitable reperfusion phase associated with oxidative stress, cellular dysfunction and altered signal transduction.

During this process, alterations in oxygen transport pathways can result in cellular hypoxia and/or dysoxia. In this context, the distinction between hypoxia and dysoxia is that cellular hypoxia refers to the condition of decreased availability of oxygen due to inadequate convective delivery from the microcirculation. Cellular dysoxia, in contrast, refers to a pathological condition where the ability of mitochondria to perform oxidative phosphorylation is limited, regardless of the amount of available oxygen. The latter condition is associated with mitochondrial failure and/or activation of alternative pathways for oxygen consumption. Thus, we would expect that an optimal balance between oxygen supply and demand is essential to reducing damage from renal ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury (Figure 1).

Complex interactions exist between tubular injury, microvascular injury, and inflammation after renal I/R. On the one hand, insults to the tubule cells promotes the liberation of a number of inflammatory mediators, such as TNF-á, IL-6, TGF-â, and chemotactic cytokines (RANTES, monocyte chemotactic protein-1, ENA-78, Gro-á, and IL-8). On the other hand, chemokine production can promote leukocyte-endothelium interactions and leukocyte activation, resulting in renal blood flow impairment and the expansion of tubular damage.

renal hemodynamics and electrolyte reabsorption

Adequate medullary tissue oxygenation, in terms of balanced oxygen supply and demand, is dependent on the maintenance of medullary perfusion by adequate cortical perfusion and also on the high rate of O2 consumption required for active electrolyte transport. Furthermore, renal blood flow is closely associated with renal sodium transport.

In addition to having a limited O2 supply due to the anatomy of the microcirculation anatomy, the sensitivity of the medulla to hypoxic conditions results from this high O2 consumption. Renal sodium transport is the main O2-consuming function of the kidney and is closely linked to renal blood flow for sodium transport, particularly in the thick ascending limbs of the loop of Henle and the S3 segments of the proximal tubules.

Medullary renal blood flow is also highly dependent on cortical perfusion, with almost all descending vasa recta emerging from the efferent arteriole of juxta medullary glomeruli. A profound reduction in cortical perfusion can disrupt medullary blood flow and lead to an imbalance between O2 supply and O2 consumption. On theother hand, inhibition of tubular reabsorption by diuretics increases medullary pO2 by decreasing the activity of Na+/K+-ATPases and local O2 consumption.

Mitochondrial activity and NO-mediated O2 consumption

The medulla has been found to be the main site of production of NO in the kidney. In addition to the actions described above, NO appears to be a key regulator of renal tubule cell metabolism by inhibiting the activity of the Na+-K+-2Cl– cotransporter and reducing Na+/H+ exchange. Since superoxide (O2–) is required to inhibit solute transport activity, it was assumed that these effects were mediated by peroxynitrite (OONO–). Indeed, mitochondrial nNOS upregulation, together with an increase in NO production, has been shown to increase mitochondrial peroxynitrite generation, which in turn, can induce cytochrome c release and promote apoptosis. NO has also been shown to directly compete with O2 at the mitochondrial level. These findings support the idea that NO acts as an endogenous regulator to match O2 supply to O2 consumption, especially in the renal medulla.

NO reversibly binds to the O2 binding site of cytochrome oxidase, and acts as a potent, rapid, and reversible inhibitor of cytochrome oxidase in competition with molecular O2. This inhibition could be dependent on the O2 level, since the IC50 (the concentration of NO that reduces the specified response by half) decreases with reduction in O2 concentration. The inhibition of electron flux at the cytochrome oxidase level switches the electron transport chain to a reduced state, and consequently leads to depolarization of the mitochondrial membrane potential and electron leakage.

To summarize, while the NO/O2 ratio can act as a regulator of cellular O2 consumption by matching decreases in O2 delivery to decreases in cellular O2 cellular, the inhibitory effect of NO on mitochondrial respiration under hypoxic conditions further impairs cellular aerobic metabolism This leads to a state of “cytopathic hypoxia,” as described in the sepsis literature.

Only cell-secreted NO competes with O2 and to regulate mitochondrial respiration. In addition to the 3 isoforms (eNOS, iNOS, cnNOS), an α-isoform of neuronal NOS, the mitochondrial isoform (mNOS) located in the inner mitochondrial membrane, has also been shown to regulate mitochondrial respiration.

These data support a role for NO in the balanced regulation of renal O2 supply and O2 consumption after renal I/R However, the relationships between the determinants of O2 supply, O2 consumption, and renal function, and their relation to renal damage remain largely unknown.

Sustained endothelial activation

Ischemic renal failure leads to persistent endothelial activation, mainly in the form of endothelium-leukocyte interactions and the activation of adhesion molecules.

This persistent activation can

- compromise renal blood flow,

- prevent the recovery of adequate tissue oxygenation, and

- jeopardize tubular cell survival despite the initial recovery of renal tubular function.

A 30-50% reduction in microvascular density was seen 40 weeks after renal ischemic injury in a rat model. Vascular rarefaction has been proposed to induce chronic hypoxia resulting in tubulointerstitial fibrosis via the molecular activation of fibrogenic factors such as

- transforming growth factor (TGF)-β,

- collagen, and

- fibronectin,

all of which may play an important role in the progression of chronic renal disease.

Adaptation to hypoxia

Over the last decade, the role of hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs) in O2 supply and adaptation to hypoxic conditions has found increasing support. HIFs are O2-sensitive transcription factors involved in O2-dependent gene regulation that mediate cellular adaptation to O2 deprivation and tissue protection under hypoxic conditions in the kidney.

NO generation can promote HIF-1α accumulation in a cGMP-independent manner. However, Hagen et al. (2003) showed that NO may reduce the activation of HIF in hypoxia via the inhibitory effect of NO on cytochrome oxidase. Therefore, it seems that NO has pleiotropic effects on HIF expression, with various responses related to different pathways.

HIF-1α upregulates a number of factors implicated in cytoprotection, including angiogenic growth factors, such as

- vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGF),

- endothelial progenitor cell recruitment via the endothelial expression of SDF-1,

- heme-oxygenase-1 (HO-1), and

- erythropoietin (EPO), and

- vasomotor regulation.

HO-1 produces carbon monoxide (a potent vasodilator) while degrading heme, which may preserve tissue blood flow during reperfusion. Thus, it has been suggested that

- the induction of HO-1 can protect the kidney from ischemic damage by decreasing oxidative damage and NO generation.

- in addition to its anti-apoptotic properties, EPO may protect the kidney from ischemic damage by restoring the renal microcirculation

(by stimulating the mobilization and differentiation of progenitor cells toward an endothelial phenotype and by inducing NO release from eNOS).

Pharmacological interventions

Use of pharmacological interventions which act at the microcirculatory level may be a successful strategy to overcome ischemia-induced vascular damage and prevent ARF.

Activated protein C (APC), an endogenous vitamin K-dependent serine protease with multiple biological activities, may meet these criteria. Along with antithrombotic and profibrinolytic properties, APC can reduce the chemotaxis and interactions of leukocytes with activated endothelium. However, renal dysfunction was not improved in the largest study published so far. In addition, APC has been discontinued by Lilly for the use intended in severe sepsis.

- neither drugs with renal vasodilatory effects (i.e., dopamine, fenoldopam, endothelin receptors blockers, adenosine antagonists) or

- agents that decrease renal oxygen consumption (i.e., loop diuretics) have been shown to protect the kidney from ischemic damage.

We have to bear in mind that a magic bullet to treat the highly complex condition of which is renal I/R is not in sight. We can expect that understanding the balance between O2 delivery and O2 consumption, as well as the function of O2-consuming pathways (i.e., mitochondrial function, reactive oxygen species generation) will be central to this treatment strategy.

Take home point

The deleterious effects of NO are thought to be associated with the NO generated by the induction of iNOS and its contribution to oxidative stress both resulting in vascular dysfunction and tissue damage. Ischemic injury also leads to structural damage to the endothelium and leukocyte infiltration. Consequently, renal tissue hypoxia is proposed to promote the initial tubular damage, leading to acute organ dysfunction.

Comment: I express great appreciation for refeering to this work, which does provide enormous new insights into hypoxia-induced acute renal failure, and ties together the anatomy, physiology, and gene regulation through signaling pathways.

Ince C, Legrand M, Mik E , Johannes T, Payen D. Renal Hypoxia and Dysoxia following Reperfusion of the Ischemic Kidney. Molecular Medicine (Proof) 2008; pp36. www.molmed.org

English: Major cellular sources of ROS in living cells. Novo and Parola Fibrogenesis & Tissue Repair 2008 1:5 doi:10.1186/1755-1536-1-5 (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Nitric oxide and non-hemodynamic functions of the kidney

One of the major scientific advances in the past decade in understanding of the renal function and disease is the prolific growth of literature incriminating nitric oxide (NO) in renal physiology and pathophysiology. NO was first shown to be identical with endothelial derived relaxing factor (EDRF) in 1987 and this was followed by a rapid flurry of information defining the significance of NO in not only vascular physiology and hemodynamics but also in neurotransmission, inflammation and immune defense systems.

Although most actions of NO are mediated by cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) signaling, S-nitrosylation of cysteine residues in target proteins constitutes another well defined non-cGMP dependent mechanism of NO effects.

Recent years have witnessed a phenomenal scientific interest in the vascular biology, particularly the relevance of nitric oxide (NO) in cardiovascular and renal physiology and pathophysiology. Although hemodynamic actions of NO received initial attention, a variety of non-hemodynamic actions are now known to be mediated by NO in the normal kidney,which include

- tubular transport of electrolyte and water,

- maintenance of acid-base homeostasis,

- modulation of glomerular and interstitial functions,

- renin-angiotensin activation and

- regulation of immune defense mechanism in the kidney.

Table 1 : Functions of NO in the kidney

1. Renal macrovascular and microvascular dilatation (afferent > efferent)

2. Regulation of mitochondrial respiration.

3. Modulation renal medullary blood flow

4. Stimulation of fluid, sodium and HCO3 – reabsorption in the proximal tubule

5. Stimulation of renal acidification in proximal tubule by stimulation of NHE activity

6. Inhibition of Na+, Cl- and HCO3 – reabsorption in the mTALH

7. Inhibition of Na+ conductance in the CCD

8. Inhibition of H+-ATPase in CCD

One of the renal regulatory mechanisms related to maintenance of arterial blood pressure involves the phenomenon of pressure-natriuresis in response to elevation of arterial pressure. This effect implies inhibition of tubular sodium reabsorption resulting in natriuresis, in an effort to lower arterial pressure. Experimental evidence indicates that intra-renal NO modulates pressure natriuresis.

Furthermore many studies have confirmed the role of intra renal NO in mediating tubulo-glomerular feedback (TGF). In vivo micropuncture studies have shown that NO derived from nNOS in macula densa specifically inhibits the TGF responses leading to renal afferent arteriolar vasoconstriction in response to sodium reabsorption in the distal tubule. Other recent studies support the inhibitory role of NO from eNOS and iNOS in mTALH segment on TGF effects.

Recent observations in vascular biology have yielded new information that endothelial dysfunction early in the course might contribute to the pathophysiology of acute renal failure. Structural and functional changes in the vascular endothelium are demonstrable in early ischemic renal failure. Altered NO production and /or decreased bioavailability of NO comprise the endothelial dysfunction in acute renal failure.

Several studies have indicated imbalance of NOS activity with enhanced expression and activity of iNOS and decreased eNOS in ischemic kidneys. The imbalance results from enhanced iNOS activity and attenuated eNOS activity in the kidney.

Many experimental studies support a contributory role for NO in glomerulonephritis (GN). Evidence from recent studies pointed out that NO may be involved in peroxynitrite formation, pro-inflammatory chemokines and signaling pathways in addition to direct glomerular effects that promote albumin permeability in GN.

Although originally macrophages and other leukocytes were first considered as the source renal NO production in GN, it is now clear iNOS derived NO from glomerular mesangial cells are the primary source of NO in GN.

In most pathological states, the role of NO is

- dependent on the stage of the disease,

- the nitric oxide synthase (NOS) isoform involved and

- the presence or absence of other modifying intrarenal factors.

Additionally NO may have a dual role in several disease states of the kidney such as

- acute renal failure,

- inflammatory nephritides,

- diabetic nephropathy and

- transplant rejection.

A rapidly growing body of evidence supports a critical role for NO in tubulointerstitial nephritis (TIN). In the rat model of autoimmune TIN, Gabbai et al. demonstrated increased iNOS expression in the kidney and NO metabolites in urine and plasma. However the effects of iNOS on renal damage in TIN seem to have a biphasic effect- since iNOS specific inhibitors (eg. L-Nil) are renoprotective in the acute phase while they actually accelerated the renal damage in the chronic phase. Thus chronic NOS inhibition is used to induce chronic tubulointerstitial injury and fibrosis along with mild glomerulosclerosis and hypertension.

Major pathways of L-arginine metabolism.

- L-arginine may be metabolized by the urea cycle enzyme arginase to L-ornithine and urea

- by arginine decarboxylase to agmatine and CO2 or

- by NOS to nitric oxide (NO) and L-citrulline.

Adapted from Klahr S: Can L-arginine manipulation reduce renal disease? Semin Nephrol 1999; 61:304-309.

It is obvious that kidney is not only a major source of arginine and nitric oxide but NO plays an important role in the water and electrolyte balance and acid-base physiology and many other homeostatic functions in the kidney. Unfortunately we are far from a precise understanding of the significance of NO alterations in various disease states primarily due to conflicting data from the existing literature.

Therapeutic potential for manipulation of L-arginine- nitric oxide axis in renal disease states has been discussed. More studies are required to elucidate the abnormalities in NO

metabolism in renal diseases and to confirm the therapeutic potential of L-arginine.

Sharma SP. Nitric oxide and the kidney. Indian J Nephrol 2004;14: 77-84

Inhibition of Constitutive Nitric Oxide Synthase

Excess NO generation plays a major role in the hypotension and systemic vasodilatation characteristic of sepsis. Yet the kidney response to sepsis is characterized by vasoconstriction resulting in renal dysfunction.

We have examined the roles of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and endothelial NOS (eNOS) on the renal effects of lipopolysaccharide administration by comparing the effects of specific iNOS inhibition, L-N6-(1-iminoethyl)lysine (L-NIL), and 2,4-diamino-6-hydroxy-pyrimidine vs. nonspecific NOS inhibitors (nitro-L-arginine-methylester). cGMP responses to carbamylcholine (CCh) (stimulated, basal) and sodium nitroprusside in isolated glomeruli were used as indices of eNOS and guanylate cyclase (GC) activity, respectively.

LPS significantly decreased blood pressure and GFR (P =0.05) and inhibited the cGMP response to CCh. GC activity was reciprocally increased. L-NIL and 2,4-diamino-6-hydroxy-pyrimidine administration prevented the decrease in GFR, restored the normal response to CCh, and GC activity was normalized. In vitro application of L-NIL also restored CCh responses in LPS glomeruli.

Neuronal NOS inhibitors verified that CCh responses reflected eNOS activity. L-NAME, a nonspecific inhibitor, worsened GFR, a reduction that was functional and not related to glomerular thrombosis, and eliminated the CCh response. No differences were observed in eNOS mRNA expression among the experimental groups.

Selective iNOS inhibition prevents reductions in GFR, whereas nonselective inhibition of NOS further decreases GFR. These findings suggest that the decrease in GFR after LPS is due to local inhibition of eNOS by iNOS, possibly via NO autoinhibition.