Hematopoiesis

Larry H. Bernstein, MD, FCAP, Curator

LPBI

Hematopoietic Stem Cells Use a Simple Heirarchy

https://beyondthedish.files.wordpress.com/2016/01/hematopoiesis-from-multipotent-stem-cell.jpg

These papers challenge this model by arguing that the CMP does not exist. Let me say that again – the CMP, a cell that has been identified several times in mouse and human bone marrow isolates, does not exist. When CMPs were identified from mouse and human none marrow extracts, they were isolated by means of flow cytometry, which is a very powerful technique, but relies on the assumption that the cell type you want to isolate is represented by the cell surface protein you have chosen to use for its isolation. Once the presumptive CMP was isolated, it could recapitulate the myeloid lineage when implanted into the bone marrow of laboratory animals and it could also produce all the myeloid cells in cell culture. Sounds convincing doesn’t it?

In a paper in Science magazine, Faiyaz Notta and colleagues from the University of Toronto beg to differ. By using a battery of antibodies to particular cell surface molecules, Notta and others identified 11 different cell types from umbilical cord blood, bone marrow, and human fetal liver that isolates that would have traditionally been called the CMP. It turns out that the original CMP isolate was a highly heterogeneous mixture of different cell types that were all descended from the HSC, but had different developmental potencies.

Notta and others used single-cell culture assays to determine what kinds of cells these different cell types would make. Almost 3000 single-cell cultures later, it was clear that the majority of the cultured cells were unipotent (could differentiate into only one cell type) rather than multipotent. In fact, the cell that makes platelets, the megakarocyte, seems to derive directly from the MPP, which jives with the identification of megakarocyte progenitors within the HSC compartment of bone marrow that make platelets “speedy quick” in response to stress (see R. Yamamoto et al., Cell 154, 1112 (2013); S. Haas, Cell Stem Cell 17, 422 (2015)).

Another paper in the journal Cell by Paul and others from the Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel examined over 2700 mouse CMPs and subjected these cells to gene expression analyses (so-called single-cell transriptome analysis). If the CMP is truly multipotent, then you would expect it to express genes associated with lots of different lineages, but that is not what Paul and others found. Instead, their examination of 3461 genes revealed 19 different progenitor subpopulations, and each of these was primed toward one of the seven myeloid cell fates. Once again, the presumptive CMPs looked very unipotent at the level of gene expression.

One particular subpopulation of cells had all the trappings of becoming a red blood cell and there was no indication that these cells expressed any of the megakarocyte-specific genes you would expect to find if MEPS truly existed. Once again, it looks as though unipotency is the main rule once the MPP commits to a particular cell lineage.

Thus, it looks as though either the CMP is a very short-lived state or that it does not exist in mouse and human bone marrow. Paul and others did show that cells that could differentiate into more than one cell type can appear when regulation is perturbed, which suggests that under pathological conditions, this system has a degree of plasticity that allows the body to compensate for losses of particular cell lineages.

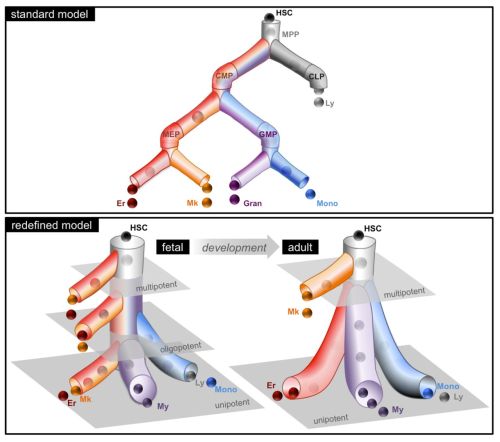

Graphical depiction of My-Er-Mk cell differentiation that encompasses the predominant lineage potential of progenitor subsets; the standard model is shown for comparison. The redefined model proposes a developmental shift in the progenitor cell architecture from the fetus, where many stem and progenitor cell types are multipotent, to the adult, where the stem cell compartment is multipotent but the progenitors are unipotent. The grayed planes represent theoretical tiers of differentiation.

Fetal HSCs, however, are a bird of a different feather, since they divide quickly and reside in fetal liver. Also, these HSCs seem to produce CMPs, which is more in line with the classical model. Does the environmental difference or fetal liver and bone marrow make the difference? In adult bone marrow, some HSCs nestle next to blood vessels where they encounter cells that hang around blood vessels known as “pericytes.” These pericytes sport a host of cell surface molecules that affect the proliferative status of HSCs (e.g., nestin, NG2). What about fetal liver? That’s not so clear – until now.

In the same issue of Science magazine, Khan and others from the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx, New York, report that fetal liver also has pericytes that express the same cell surface molecules as the ones in bone marrow, and the removal of these cells reduces the numbers of and proliferative status of fetal liver HSCs.

Now we have a conundrum, because the same cells in bone marrow do not drive HSC proliferation, but instead drive HSC quiescence. What gives? Khan and others showed that the fetal liver pericytes are part of an expanding and constantly remodeling blood system in the liver and this growing, dynamic environment fosters a proliferative behavior in the fetal HSCs.

When umbilical inlet is closed at birth, the liver pericytes stop expressing Nestin and NG2, which drives the HSCs from the fetal liver to the other place were such molecules are found in abundance – the bone marrow.

These models give us a better view of the inner workings of HSC differentiation. Since HSC transplantation is one of the mainstays of leukemia and lymphoma treatment, understanding HSC biology more perfectly will certainly yield clinical pay dirt in the future.

In a classical view of hematopoiesis, the various blood cell lineages arise via a hierarchical scheme starting with multipotent stem cells that become increasingly restricted in their differentiation potential through oligopotent and then unipotent progenitors. We developed a cell-sorting scheme to resolve myeloid (My), erythroid (Er), and megakaryocytic (Mk) fates from single CD34+ cells and then mapped the progenitor hierarchy across human development. Fetal liver contained large numbers of distinct oligopotent progenitors with intermingled My, Er, and Mk fates. However, few oligopotent progenitor intermediates were present in the adult bone marrow. Instead, only two progenitor classes predominate, multipotent and unipotent, with Er-Mk lineages emerging from multipotent cells. The developmental shift to an adult “two-tier” hierarchy challenges current dogma and provides a revised framework to understand normal and disease states of human hematopoiesis.

Transcriptional Heterogeneity and Lineage Commitment in Myeloid Progenitors

Jalal A. Khan, et al. Science 08 Jan 2016; 351(6269):176-180 http://dx.doi.org:/10.1126/science.aad0084

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) undergo dramatic expansion in the fetal liver before migrating to their definitive site in the bone marrow. Khan et al. identify portal vessel–associated Nestin+NG2+ pericytes as critical HSC niche components (see the Perspective by Cabezas-Wallscheid and Trumpp). The portal vessel niche and HSCs expand according to fractal geometries, suggesting that niche cells—rather than factors expressed by the niche—drive HSC proliferation. After birth, arterial portal vessels transform into portal veins, and lose Nestin+NG2+pericytes. When this happens, the niche is lost and HSCs migrate away from the neonatal liver.

Whereas the cellular basis of the hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) niche in the bone marrow has been characterized, the nature of the fetal liver niche is not yet elucidated. We show that Nestin+NG2+ pericytes associate with portal vessels, forming a niche promoting HSC expansion. Nestin+NG2+ cells and HSCs scale during development with the fractal branching patterns of portal vessels, tributaries of the umbilical vein. After closure of the umbilical inlet at birth, portal vessels undergo a transition from Neuropilin-1+Ephrin-B2+ artery to EphB4+ vein phenotype, associated with a loss of periportal Nestin+NG2+ cells and emigration of HSCs away from portal vessels. These data support a model in which HSCs are titrated against a periportal vascular niche with a fractal-like organization enabled by placental circulation.