Revascularization: PCI, Prior History of PCI vs CABG

Curator: Aviva Lev-Ari, PhD, RN

UPDATED 9/25/2013

Table. Comparison of Surgical Therapy and Coronary Angioplasty (Open Table in a new window)

| Endpoint | Pocock et al* | Pocock et al† | BARI Study‡ | |||

| CABG(N=358) | PTCA(N=374) | CABG(N=1303) | PTCA(N=1336) | CABG(N=914) | PTCA(N=915) | |

| Death (%) | 0.3 | 1.9 | 2.8 | 3.1 | 10.7 | 13.7 |

| Death or MI | 4.5 | 7.2 | 8.5 | 8.1 | 11.7 | 10.9 |

| Repeat CABG | 1.4 | 16.0§ | 0.8 | 18.3§ | 0.7 | 20.5§ |

| Repeat CABG or PTCA | 3.6 | 30.5§ | 3.2 | 34.5§ | 8.0 | 54.0§ |

| More than mild angina | 6.5 | 14.6§ | 12.1 | 17.8§ | … | … |

| *Meta-analysis of results of 3 trials at 1 year. Patients with single-vessel disease were studied.[22] †Meta-analysis of results of 3 trials at 1 year. Patients with multivessel disease were studied.[22]

‡Reported results are for 5-year follow-up. Patients with multivessel disease were studied.[21] § P < .05. BARI = Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation; CABG = coronary artery bypass grafting; MI = myocardial infarction; PTCA = percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. SOURCE http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/161446-overview#aw2aab6b2b5 |

||||||

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), also known as coronary angioplasty, is a nonsurgical technique for treating multiple conditions, including unstable angina, acute myocardial infarction (MI), and multivessel coronary artery disease (CAD).

Essential update: Cangrelor decreases periprocedural complications of PCI

According to a pooled analysis of 3 CHAMPION trials—CHAMPION-PCI , CHAMPION-PLATFORM , and CHAMPION-PHOENIX—cangrelor can reduce the risk of periprocedural thrombotic complications of PCI.[1, 2, 3] The 3 trials included patients with ST-elevation MI (STEMI), non-STEMI, and stable CAD who were randomly assigned to receive either cangrelor or control therapy consisting of either clopidogrel or placebo.

The primary outcome in this analysis was a composite of death, MI, ischemia-driven revascularization, or stent thrombosis at 48 hours.[2] The frequency of this outcome was significantly lower in cangrelor-treated patients than in control subjects (absolute difference, 1.9%; relative risk reduction [RRR], 19%). Stent thrombosis was also reduced in the cangrelor-treated group (absolute difference, 0.3%; RRR, 41%). Primary safety outcomes were comparable in the 2 groups, but cangrelor-treated patients had a higher rate of mild bleeding.

Indications and contraindications

Clinical indications for PCI include the following:

-

Acute STEMI

-

Non–ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome (NSTE-ACS)

-

Anginal equivalent (eg, dyspnea, arrhythmia, or dizziness or syncope)

In an asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic patient, objective evidence of a moderate-sized to large area of viable myocardium or moderate to severe ischemia on noninvasive testing is an indication for PCI. Angiographic indications include hemodynamically significant lesions in vessels serving viable myocardium (vessel diameter >1.5 mm).

Clinical contraindications for PCI include the presence of any significant comorbid conditions (this is a relative contraindication). Angiographic contraindications include the following:

-

Left main stenosis in a patient who is a surgical candidate (except in carefully selected patients[4] )

-

Diffusely diseased small-caliber artery or vein graft

-

Other coronary anatomy not amenable to PCI

In patients with stable angina, medical therapy is recommended as first-line therapy unless one or more of the following indications for cardiac catheterization and PCI or CABG are present:

-

A change in symptom severity

-

Failed medical therapy

-

High-risk coronary anatomy

-

Worsening left ventricular (LV) dysfunction

American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association (ACCF/AHA) guidelines on the management of unstable angina/non-STEMI recommend that an early invasive approach (angiography and revascularization within 24 hours) should be used to treat patients presenting with the following high-risk features[5] :

-

Recurrent angina at rest or low level of activity

-

Elevated cardiac biomarkers

-

PCI in the past 6 months or prior CABG

-

New ST-segment depression

-

Elevated cardiac biomarkers

-

High-risk findings on noninvasive testing

-

Signs or symptoms of heart failure or new or worsening mitral regurgitation

-

Hemodynamic instability

-

Sustained ventricular tachycardia

-

LV systolic function < 40%

-

High risk score (eg, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction [TIMI] score >2) (see the TIMI Score for Unstable Angina Non ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction calculator)

See Overview for more detail.

Equipment

Balloon catheters for PCI have the following features:

-

A steerable guide wire precedes the balloon into the artery and permits navigation through the coronary tree

-

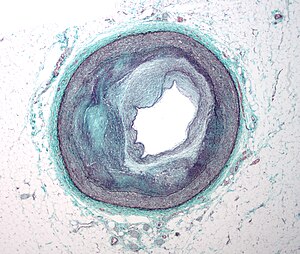

Inflation of the balloon compresses and axially redistributes atheromatous plaque and stretches the vessel wall

-

The balloon catheter also serves as an adjunctive device for many other interventional therapies

Atherectomy devices have the following features:

-

These devices are designed to physically remove coronary atheroma, calcium, and excess cellular material

-

Rotational atherectomy, which relies on plaque abrasion and pulverization, is used mostly for fibrotic or heavily calcified lesions that can be wired but not crossed or dilated by a balloon catheter

-

Atherectomy devices may be used to facilitate stent delivery in complex lesions

-

Directional coronary atherectomy (DCA) has been used to debulk coronary plaques

-

Laser atherectomy is not widely used at present

-

Atherectomy is typically followed by balloon dilation and stenting

Intracoronary stents have the following features:

-

Stents differ with respect to composition (eg, stainless steel, cobalt chromium, or nickel chromium), architectural design, and delivery system

-

Drug-eluting stents have demonstrated significant reductions in restenosis and target-lesion revascularization rates

-

In the United States, stents are available that elute the following drugs: sirolimus (Cypher), paclitaxel (Taxus), zotarolimus (Endeavor), and everolimus (Xience V)

-

Stents are conventionally placed after balloon predilation, but in selected coronary lesions, direct stenting may lead to better outcomes

Other devices used for PCI include the following:

-

Thrombus aspiration limits the adverse effects that prolonged time to treatment has on myocardial reperfusion[6]

-

Distal embolic protection during saphenous vein graft intervention has become the standard of care

See Periprocedural Care and Devices for more detail.

Technique

Intravascular ultrasonography (IVUS) is used in PCI as follows:

-

Provide information about the plaque, the vessel wall, and the degree of luminal narrowing

-

Assessment of indeterminate lesions

-

Evaluation of adequate stent deployment

Intracoronary Doppler pressure wires are used in PCI as follows:

-

To characterize coronary lesion physiology and estimate lesion severity

-

Comparison of pressure distal to a lesion with aortic pressure enables determination of fractional flow reserve (FFR)

-

An FFR measurement below 0.75-0.80 during maximal hyperemia (induced via administration of adenosine) is consistent with a hemodynamically significant lesion

Antithrombotic therapy

-

Aspirin and heparin have been the traditional adjunctive medical therapies

-

Direct thrombin inhibitors (ie, hirudin, bivalirudin) are slightly better than heparin in preventing ischemic complications during balloon angioplasty but do not affect restenosis rates

-

Low-molecular-weight heparins (LMWHs) are substituted for standard heparin at some centers

Antiplatelet therapy

Patients receiving stents are treated with a combination of aspirin and clopidogrel. Duration of therapy is as follows:

-

Bare-metal stents: A minimum of 4 weeks

-

Drug-eluting stents: A minimum of 12 months

Use of proton pump inhibitors is appropriate in patients with multiple risk factors for GI bleeding who require antiplatelet therapy.

Glycoprotein inhibitor therapy

-

Abciximab, tirofiban, and eptifibatide have all been shown to reduce ischemic complications in patients undergoing balloon angioplasty and coronary stenting

-

In primary PCI, GPIIb/IIIa receptor inhibitors have also been shown to improve flow and perfusion and to reduce adverse events

-

Abciximab may improve outcomes in patients when given before arrival in the catheterization lab for primary PCI[7]

See Technique and Medication for more detail.

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/161446-overview#aw2aab6b2b5

Outcomes comparison between PCI and CABG was explored in the past by authors on this Open Access Online Scientific Journal, in the following articles:

CABG or PCI: Patients with Diabetes – CABG Rein Supreme

To Stent or Not? A Critical Decision

http://pharmaceuticalintelligence.com/2012/10/23/to-stent-or-not-a-critical-decision/

PCI Outcomes, Increased Ischemic Risk associated with Elevated Plasma Fibrinogen not Platelet Reactivity

New Definition of MI Unveiled, Fractional Flow Reserve (FFR)CT for Tagging Ischemia

Age-Dependent Depression in Circulating Endothelial Progenitor Cells in Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting Patients

Now we are reporting an Original Contribution on this subject which includes also Prior History of PCI, a factor NOT included in the other studies. The major conclusions are the following three:

- In a contemporary cohort of STEMI patients undergoing primary PCI, a history of prior CABG was found to be an independent predictor of in-hospital mortality.

- In contrast, despite more comorbidities at the time of STEMI, patients with prior PCI had no significant difference in the rates of death, stroke, or periprocedural MI when compared to a STEMI population without prior coronary revascularization.

- Thus, only prior surgical — and not percutaneous — revascularization should be considered a significant risk factor in the setting of primary PCI.

Number 1, above is related to patient medical history of cardiovascular disease SEVERITY prior to CABG

Number 2, above indicates that patients can tolerate and benefit several cycles of PCI and stent implantation rather than PCI being a determinant predictor of future prognosis

Number 3, above is as well related to patient medical history of cardiovascular disease SEVERITY prior to CABG

The Original Contribution on this subject is present, below.

The Impact of Previous Revascularization on Clinical Outcomes in Patients Undergoing Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention

Travis J. Bench, MD1, Puja B. Parikh, MD1, Allen Jeremias, MD1, Sorin J. Brener, MD2, Srihari S. Naidu, MD3,

Richard A. Shlofmitz, MD4, Thomas Pappas, MD4, Kevin P. Marzo, MD3, Luis Gruberg, MD1

Authors Affiliations:

1Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Stony Brook University Medical Center, Stony Brook, New York,

2Department of Cardiology, Methodist Hospital, Brooklyn, New York,

3Division of Cardiology, Winthrop University Hospital, Mineola,

New York, and

4The Heart Center, St Francis Hospital, Roslyn, New York.

The authors report no conflicts of interest regarding the content herein.

Manuscript submitted October 10, 2012, provisional acceptance given October 20, 2012, final version accepted November 28, 2012.

Address for correspondence:

Luis Gruberg, MD, FACC, Department of Medicine, Division of Cardiology, Health Sciences Center, T16-080, Stony Brook, NY 11794- 8160. Email: luis.gruberg@stonybrook.edu

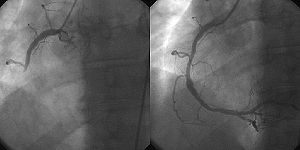

Abstract : While the impact of prior coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG) on in-hospital outcomes in patients with STelevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) has been described, data are limited on patients with prior percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) undergoing primary PCI in the setting of an STEMI. The aim of the present study was to assess the effect of previous revascularization on in-hospital outcomes in STEMI patients undergoing primary PCI. Between January 2004 and December 2007, a total of 1649 patients underwent primary PCI for STEMI at four New York State hospitals. Baseline clinical and angiographic characteristics and in-hospital outcomes were prospectively collected as part of the New York State PCI Reporting System (PCIRS). Patients with prior surgical or percutaneous coronary revascularization were compared to those without prior coronary revascularization. Of the 1649 patients presenting with STEMI, a total of 93 (5.6%) had prior CABG, 258 (15.7%) had prior PCI, and 1298 (78.7%) had no history of prior coronary revascularization. Patients with prior CABG were significantly older and had higher rates of peripheral vascular disease, diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, and prior stroke. Additionally, compared with those patients with a history of prior PCI as well as those without prior coronary revascularization, patients with previous CABG had more left main interventions (24% vs 2% and 2%; P<.001), but were less often treated with drug-eluting stents (47% vs 61% and 72%; P<.001).

Despite a low incidence of adverse in-hospital events, prior CABG was associated with higher all-cause in-hospital mortality (6.5% vs 2.2%; P=.012), and as a result, higher overall MACE (6.5% vs 2.7%; P=.039). By multivariate analysis, prior CABG (odds ratio, 3.40; 95% confidence interval, 1.15-10.00) was independently associated with in-hospital mortality. In contrast, patients with prior PCI had similar rates of MACE (4.3% vs 2.7%; P=.18) and inhospital mortality (3.1% vs 2.2%; P=.4) when compared to the de novo population. Patients with a prior history of CABG, but not prior PCI, undergoing primary PCI in the setting of STEMI have significantly worse in-hospital outcomes when compared with patients who had no prior history of coronary artery revascularization. Thus, only prior surgical — and not percutaneous — revascularization should be considered a significant risk factor in the setting of primary PCI.

J INVASIVE CARDIOL 2013;25(4):166-169

Key words: PCI risk factor, CABG

Demographics and Angiographic Characteristics

Between 2004 and 2007, a total of 25,025 patients underwent PCI at these medical institutions, and their data were prospectively collected and submitted as required by the New York State Department of Health. Of these patients, a total of 1649 underwent primary PCI in the setting of an STEMI and constituted our study population. In this group, a total

No Prior Revascularization (n = 1298)

Prior PCI (n = 258)

Prior CABG (n = 93)

Demographics

Age (years) 61 ± 13 62 ± 12 67 ± 12 <.001

Male gender 956 (73.6%) 194 (75.2%) 76 (81.7%) .21

White 1165 (89.8%) 231 (89.5%) 87 (93.5%) .51

African-American 78 (6%) 18 (7%) 1 (1.1%) .51

Hispanic 91 (7%) 11 (4.3%) 4 (4.3%) .51

Medical history

Ejection fraction (%) 43 ± 12 44 ± 13 45 ± 11 .079

Diabetes mellitus 196 (15.1%) 69 (26.7%) 27 (29%) <.001

Peripheral vascular disease 53 (4.1%) 25 (9.7%) 12 (12.9%) <.001

Chronic lung disease 47 (3.6%) 17 (6.6%) 4 (4.3%) .09

Congestive heart failure 74 (5.7%) 25 (9.7%) 10 (10.8%) .02

Prior myocardial infarction 3 (0.2%) 1 (0.4%) 1 (1.1%) .35

Prior cerebrovascular event 56 (4.3%) 9 (3.5%) 10 (11%) .01

Chronic dialysis 6 (0.5%) 6 (2.3%) 0 (0%) .004

Creatinine (mg/dL) 1.1 ± 0.8 1.3 ± 1.4 1.3 ± 1.1 .002

Glomerular filtration rate (mL/min/1.73 m2) 79 ± 26 75 ± 28 71 ± 27 .002

Angiographic characteristics

Left main 19 (1.5%) 5 (1.9%) 22 (23.7%) <.001

Left anterior descending 942 (72.6%) 178 (69%) 69 (74.2%) .45

Left circumflex 579 (44.6%) 122 (47.3%) 70 (75.3%) <.001

Right coronary 806 (62.1%) 187 (72.5%) 67 (72%) .002

Graft (arterial or venous) n/a n/a 20 (21.5%)

Stent type

Bare-metal stent 241 (18.6%) 52 (20.2%) 23 (24.7%) .31

Drug-eluting stent 928 (71.5%) 158 (61.2%) 44 (47.3%) <.001

of 1298 patients (78.7%) had no prior history of revascularization,

while 93 patients (5.6%) had a history of previous

CABG and 258 (15.7%) had a history of previous PCI. Considerable

differences in baseline clinical and procedural characteristics were noted among these groups (Table 1).

Discussion

While STEMI patients with prior CABG are well known to have worse clinical outcomes than those without prior revascularization, a direct comparison between patients who underwent primary PCI in the setting of prior CABG or prior PCI has not yet been reported. The principal findings from the present analysis suggest that in a contemporary, unrestricted patient population presenting with STEMI and undergoing primary PCI, patients with a prior history of CABG are:

(1) usually older and have multiple comorbidities, including peripheral vascular disease, diabetes, and chronic obstructive lung disease;

(2) are more likely to undergo intervention on a native vessel and not a bypass graft;

(3) are more likely to be treated with bare-metal stents; and (4) have higher rates of in-hospital mortality without a significant increase in stroke or MI rates, when compared with patients with a prior history of PCI or patients with no previous history of coronary artery revascularization. Interestingly, these outcomes did not apply to patients with a history of prior PCI in this analysis. Instead, this cohort of patients had no significant difference in the rate of death, stroke, or periprocedural infarction when compared to a STEMI population without prior coronary revascularization, despite a significantly higher burden of comorbidities than those with no prior revascularization.

Our findings concur with previous studies that have shown higher mortality rates among patients with prior surgical bypass presenting with acute MI.7,9,14 Despite changes in revascularization strategies over the past 30 years, invasive therapies to treat acute coronary syndromes in patients with prior bypass surgery appear to have yielded less robust results than in other populations. In fact, Stone and colleagues already described in the Primary Angioplasty in Myocardial Infarction (PAMI-2) study that patients with a previous CABG undergoing primary PCI in the setting of an acute MI had significantly greater in-hospital mortality than patients without previous CABG, especially if the infarct-related vessel was a bypass conduit. However, by logistic regression analysis, only advanced age (P=.004), triple-vessel disease (P=.004), and Killip class ≥2 (P=.02) were independent predictors of in-hospital mortality in that study.13 In a more contemporary study of 128 STEMI patients with prior CABG, who were enrolled in the Assessment of PEXelizumab in Acute

Figure 1. In-hospital major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE), mortality, and stroke rates for patients without prior history of coronary revascularization (light grey bars), prior percutaneous coronary revascularization (PCI) (dark grey bars), and prior coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) (black bars). Vol. 25, No. 4, April 2013 169

STEMI and Prior Revascularization Myocardial Infarction (APEX-AMI) trial, Welsh and colleagues reported that post-CABG patients are less likely to undergo acute reperfusion (only 79% underwent primary PCI), have worse angiographic outcomes following primary PCI, and have higher 90-day mortality rates (19.0% vs 5.7%; P=.05). This difference was even more apparent when the infarct-related artery was a bypass graft that was not successfully reperfused (23.1% vs 8.5%; P=.03).3 These results are similar to our current analysis, where in-hospital mortality rates for patients who underwent primary PCI of a graft were numerically roughly 4 times as high as those undergoing PCI of a native vessel. Likewise, Gurfinkel et al reported a significant reduction in hard endpoints, such as all-cause death and MI at 6 months in patients treated with an invasive approach in the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE).15 In this large, multinational, observational study of 3853 patients with prior bypass surgery presenting with an acute coronary syndrome, only 497 (12.9%) were managed invasively and the rest were treated medically.

Despite significant differences in baseline characteristics, including a higher rate of STEMI in patients treated invasively (14% vs 27%; P<.001), in-hospital mortality was similar in both groups (3.4% vs 3.2%; P=.86). However, at 6-month follow-up, mortality was significantly higher in those patients treated medically (6.5% vs 3.4%; P<.02) as was the combined endpoint of death or MI (11% vs 5.8%; P<.01).

Whether these results apply to patients with a prior history of PCI has not been well defined. By the nature of vascular disease, patients with prior PCI are more likely to have more comorbidities than those without prior revascularization, a finding confirmed in our study. Despite considerable differences in baseline characteristics, however, these differences did not translate into a differential risk after STEMI. In fact, the cohort of patients presenting with STEMI who had a history of prior PCI had no statistically significant difference in in-hospital mortality or overall MACCE when compared to a population of patients presenting with STEMI in the absence of any prior revascularization.

Study limitations. The database utilized was derived from four New York State teaching hospitals and was designed to track quality of care and clinical outcomes. As all studies involving multicenter databases and registries, there is potential error in data entry and availability. Potential confounding comorbidities, including smoking status and family history of coronary artery disease, were not collected in this database, and information regarding long-term follow-up is not available, all of which are important limitations of this analysis. As such, deficiencies such as these limit the conclusions that can be drawn from our multivariate analysis. Additionally, there is no audit of data quality, and the low overall event rates limit effective statistical comparison.

Conclusions

In a contemporary cohort of STEMI patients undergoing primary PCI, a history of prior CABG was found to be an independent predictor of in-hospital mortality. In contrast, despite more comorbidities at the time of STEMI, patients with prior PCI had no significant difference in the rates of death, stroke, or periprocedural MI when compared to a STEMI population without prior coronary revascularization. Thus, only prior surgical — and not percutaneous — revascularization should be considered a significant risk factor in the setting of primary PCI.

REFERENCES

1. Kushner FG, Hand M, Smith SC Jr, et al. 2009 focused updates: ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (updating the 2004 guideline and 2007 focused update) and ACC/AHA/SCAI guidelines on percutaneous coronary intervention (updating the 2005 guideline and 2007 focused update): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;74(7):E25-E68.

2. Keeley EC, Boura JA, Grines CL. Primary angioplasty versus intravenous thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: a quantitative review of 23 randomised trials. Lancet. 2003;361(9351):13-20.

3. Welsh RC, Granger CB, Westerhout CM, et al. Prior coronary artery bypass graft patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;3(3):343-351.

4. Mathew V, Gersh B, Barron H, et al. In-hospital outcome of acute myocardial infarction in patients with prior coronary artery bypass surgery. Am Heart J. 2002;144(3):463-469.

5. Lee KL, Woodlief LH, Topol EJ, et al. Predictors of 30-day mortality in the era of reperfusion for acute myocardial infarction. Results from an international trial of 41,021 patients. GUSTO-I Investigators. Circulation. 1995;91(6):1659-1668.

6. Dittrich HC, Gilpin E, Nicod P, et al. Outcome after acute myocardial infarction in patients with prior coronary artery bypass surgery. Am J Cardiol. 1993;72(7):507-513.

7. Berry C, Pieper KS, White HD, et al. Patients with prior coronary artery bypass grafting have a poor outcome after myocardial infarction: an analysis of the VALsartan in acute myocardial iNfarcTion trial (VALIANT). Eur Heart J. 2009;30(12):1450-1456.

8. Grines CL, Booth DC, Nissen SE, et al. Mechanism of acute myocardial infarction in patients with prior coronary artery bypass grafting and therapeutic implications. Am J Cardiol. 1990;65(20):1292-1296.

9. Labinaz M, Sketch MH Jr, Ellis SG, et al. Outcome of acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in patients with prior coronary artery bypass surgery receiving thrombolytic therapy. Am Heart J. 2001;141(3):469-477.

10. Peterson LR, Chandra NC, French WJ, Rogers WJ, Weaver WD, Tiefenbrunn AJ. Reperfusion therapy in patients with acute myocardial infarction and prior coronary artery bypass graft surgery (National Registry of Myocardial Infarction-2). Am J Cardiol. 1999;84(11):1287-1291.

11. Nguyen TT, O’Neill WW, Grines CL, et al. One-year survival in patients with acute myocardial infarction and a saphenous vein graft culprit treated with primary angioplasty. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91(10):1250-1254.

12. Al Suwaidi J, Velianou JL, Berger PB, et al. Primary percutaneous coronary interventions in patients with acute myocardial infarction and prior coronary artery bypass grafting, Am Heart J. 2001;142(3):452-459.

13. Stone GW, Brodie BR, Griffin JJ, et al. Clinical and angiographic outcomes in patients with previous coronary artery bypass graft surgery treated with primary balloon angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. Second Primary Angioplasty in Myocardial Infarction Trial (PAMI-2) Investigators. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35(3):605-611.

14. Labinaz M, Kilaru R, Pieper K, et al. Outcomes of patients with acute coronary syndromes and prior coronary artery bypass grafting: results from the platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa in unstable angina: receptor suppression using integrilin therapy (PURSUIT) trial. Circulation. 2002;105(3):322-327.

15. Gurfinkel EP, Perez de la Hoz R, Brito VM, et al. Invasive vs non-invasive treatment in acute coronary syndromes and prior bypass surgery. Int J Cardiol. 2007;119(1):65-72.

Other related studies on this subject published on this Open Access Online Scientific Journal include the following:

Lev-Ari, A. 2/12/2013 Clinical Trials on transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) to be conducted by American College of Cardiology and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons

Lev-Ari, A. 12/31/2012 Renal Sympathetic Denervation: Updates on the State of Medicine

Lev-Ari, A. 9/2/2012 Imbalance of Autonomic Tone: The Promise of Intravascular Stimulation of Autonomics

Lev-Ari, A. 8/13/2012 Coronary Artery Disease – Medical Devices Solutions: From First-In-Man Stent Implantation, via Medical Ethical Dilemmas to Drug Eluting Stents http://pharmaceuticalintelligence.com/2012/08/13/coronary-artery-disease-medical-devices-solutions-from-first-in-man-stent-implantation-via-medical-ethical-dilemmas-to-drug-eluting-stents/

Lev-Ari, A. 7/18/2012 Percutaneous Endocardial Ablation of Scar-Related Ventricular Tachycardia

Lev-Ari, A. 6/13/2012 Treatment of Refractory Hypertension via Percutaneous Renal Denervation

Lev-Ari, A. 6/22/2012 Competition in the Ecosystem of Medical Devices in Cardiac and Vascular Repair: Heart Valves, Stents, Catheterization Tools and Kits for Open Heart and Minimally Invasive Surgery (MIS)

Lev-Ari, A. 6/19/2012 Executive Compensation and Comparator Group Definition in the Cardiac and Vascular Medical Devices Sector: A Bright Future for Edwards Lifesciences Corporation in the Transcatheter Heart Valve Replacement Market

Lev-Ari, A. 6/22/2012 Global Supplier Strategy for Market Penetration & Partnership Options (Niche Suppliers vs. National Leaders) in the Massachusetts Cardiology & Vascular Surgery Tools and Devices Market for Cardiac Operating Rooms and Angioplasty Suites

Lev-Ari, A. 7/23/2012 Heart Remodeling by Design: Implantable Synchronized Cardiac Assist Device: Abiomed’s Symphony

Lev-Ari, A. (2006b). First-In-Man Stent Implantation Clinical Trials & Medical Ethical Dilemmas. Bouve College of Health Sciences, Northeastern University, Boston, MA 02115